Manjeera

“I believe that all women should like their bodies and use them as tools of seduction”

-Ghada Amer

Stitch by stitch, Ghada Amer takes charge and produces artistic works that aim to create an aesthetic language specific to women, reclaiming their bodies from the male gaze and reinterpreting their existing relationship with religion, society and the labour they perform. For the last two decades, Amer has received international acclaim for producing multimedia works that utilise embroidery, a craft traditionally practised by women and relegated firmly to the domestic realm, to challenge the male-dominated world of art. Her practice is wide-ranging, spanning from embroidered paintings and sculptures to paper drawings, ceramics, cast sculptures and garden installations. Amer’s unusual form of expression moulds a unique space for women in the history of painting shaped historically by expressions of masculinity and her content, focusing on an intimate look at women’s bodies and reinterpretation of religious texts, challenges the traditional roles relegated to women by both the Western and Eastern societies.

Amer was born in Cario, Egypt in 1963 but her family moved to France when she was eleven. This cross-cultural upbringing allowed Amer to witness various dimensions of subjugation– women were controlled equally by both the conservative religious oppression prevalent in Egypt as well as the Western commodity culture that reduced them to mere objects.

Amer graduated from Ecole Pilote Internationale d’Art et Recherche in Nice, where she got the first glimpse of the male-dominated art world. Amer was informed that the art school’s painting classes were exclusively reserved for male students, because the act of painting was a “male activity”. The discipline itself was controlled by chauvinistic principles that not only denied women equal access to opportunities but also lacked a distinct language to express female voices. This oppressive environment was crucial in catalysing Amer’s own unique artistic style by forcing her to experiment with different mixed-media mediums in order to mould a unique form of artistic expression, though she would only arrive at a breakthrough a few years later.

Ghada Amer’s family had moved back to Egypt in 1984 and whenever she visited them she was taken aback by the increasing conservatism caused by the changing socio-political circumstances following Anwar Sadat’s assassination. There was a noticeable regression in women’s civil rights and their personal freedom was constrained; even her own mother was compelled to wear the hijab and a strict policing of women’s bodies had begun. The choices were being systematically taken away from women, and it was during this tumultuous period that Amer came across her second catalyst in the Cario marketside– a magazine called Venus which featured Western women wearing long sleeves and veils, merging the Western clothing design with Muslim tradition. These were the key influences that formulated Amer’s approach to art, which characteristically reinterprets the position of women within the confines of Quran and between the pages of Western pornographic books.

Amer replaced the strokes of the pencil with stitches of thread in works, which allowed her to escape the historically “male tool” of painting (as she describes it). Embroidery gave her access to a more feminine form of expression and allowed her to represent women devoid of the male gaze that sexualized female bodies. She wanted women to look at their own bodies, reclaim their own pleasure as they viewed her art.

In the 1990s, Ghada Amer began to explore images of women from pornographic magazines and juxtaposed characters from Disney fairy tales into sexually suggestive positions. The representation of women by Western media has a certain dichotomy to it; the pure and virginal princesses reinforced conservative Christian gender expectations into the minds of young girls, while the sexualized figures from the pornos reduced women into mere objects for male sexual gratification. The fairy tales of Disney and other Western media inculcated young girls to set beauty standards for themselves and taught them that they are nothing without a Prince Charming. To question this, Amer stitches women from these fairy tales pleasuring themselves, or being pleasured by other women. Her acrylic and embroidered painting And the Beast (2003) perfectly depicts the message Amer wants to send while focusing its attention on female pleasure (an afterthought in male pornography). There are multiple layers to this painting that take advantage of its multiple mediums; the viewer can focus their perspective on different aspects of the painting to reveal new figures in different sexual positions. We can see a caricature of the cartoon Disney future of Belle at the background, juxtaposed by another Belle, almost unrecognisable, being pleasured in various different ways. These layered distorted images challenge the double standards inherent in representation of women by western media.

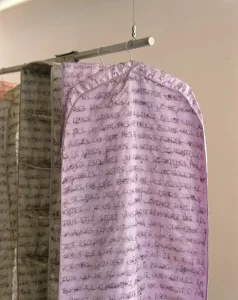

A significant portion of her work also reinterprets the Quran and other Arabic texts that have historically created a standard of morality for women. Her embroidered sculpture Private Rooms (1998) consists of colourful sets of hanging shelves embroidered with every Quranic verse that addresses or mentions women. The shelves, supposed to serve as wardrobes, represent the private space associated with women; the domestic aspect of their lived reality. This artist intended this artwork to be a space of meditation and its intention was to invite women to read the religious text directly in order to form their own interpretations. It is not a rejection of Islam, but a reclamation that overcomes religious appropriation.

Her most recent exhibition is a language-based garden installation called A Woman’s Voice Is Revolution (2022) hosted in MUCEM, Fort Saint-Jean, Marseille, France. It opened on 17th September 2022 and will remain open till 16th April 2023. The title of the work challenges a popular Arabic proverb “A Woman’s Voice is Shameful” and rewrites it using a popular protest slogan during the 2010 Arab Spring anti-government protests. This proverb originates from dubious and contested sources, but has been historically used to denounce women’s voices. These voices are treated as impure and offensive, just like a woman’s body that needs to be covered up. Conservative Muslims argue that a woman’s voice introduces religious strife, discord and tempts righteous men. Amer’s garden installation questions this mentality with firm letters created by steel structural frames. The letters are filled with coal, which is a reference to the tradition of witch-hunting- a symbol of silencing women’s voices. The rest of the space around the Arabic letters is filled with a Mediterranean medicinal plant that blooms each spring, representing the resilience of women when confronted with religious extremism, sexual violence and discrimination. This artwork and the time of its exhibition coincided with the Mahsa Amini protests in Iran and the wave of protests that followed in the Middle-East and beyond after that, protesting the moral policing of women’s bodies and voices.

Citations:

Writing the Body: The Art of Ghada Amer by Maura Reilly

https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/community/blogosphere/2008/06/06/ghada-amer-happily-ever-after/

https://www.artbasel.com/stories/ghada-amer