Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Impressionism Art

Art is about emotion; if art needs to be explained it is no longer art.

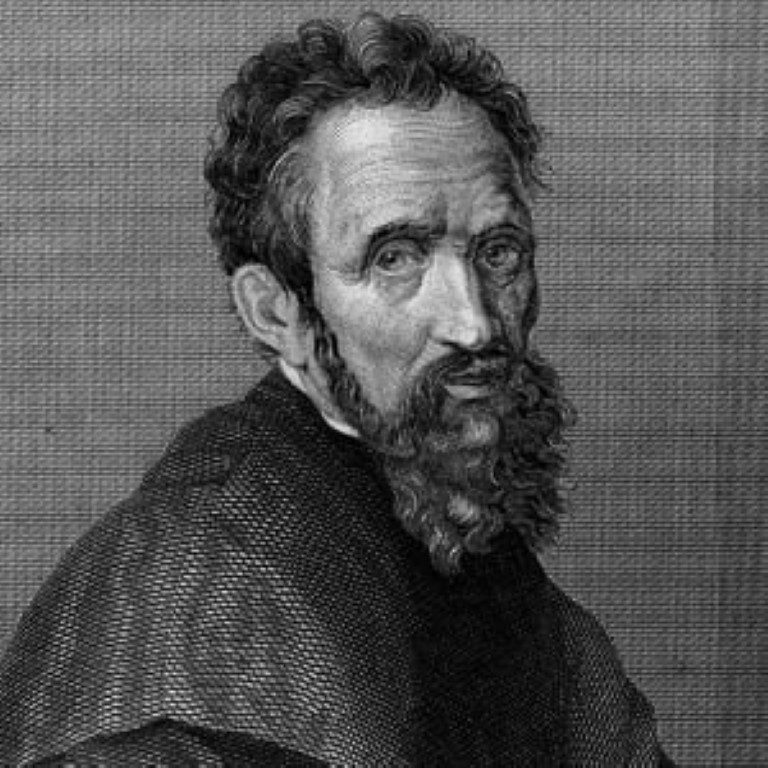

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

Renoir’s famous paintings, characterised by an atmospheric haziness that emerges as a result of his soft impasto brushwork and layering of bright colours, are perhaps the most recognisable out of all the French Impressionists. He had an eye for beauty and captured the movement of light and shadow on the canvas with such subtlety that his paintings evoked an ethereal emotion that encapsulated the essence of the figures and landscapes he was painting.

Courtesy – Mark Littler

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919) was born today, on 25th February to an artisan family, with his father being a tailor. His artistic genius was recognised quite early on, and Renoir started by painting porcelain plates, cloth panels and fans. He enrolled in the prestigious Académie des Beaux-Arts in 1862, where he met Claude Monet, Alfred Sisley and Frederic Bazille, who rejected the conventional modes of art being taught to them.

Renoir Art Style Analysis

The impressionist painters Claude Monet and Renoir, who would go on to make waves in French Impressionism art, would try to discover their style. As they rejected the traditional modes of art and the conventional artistic subject, they sought to expand their oeuvre through experimentation. Renoir and Monet painted together for 2 months in the summer of 1869 at La Grenouillère, a boating and bathing establishment outside Paris, with loose brushstrokes and attempted to capture the sun peeking through the layers of leaves reflected on rippling water.

Courtesy – Wikipedia

There is a certain haziness to both of their paintings on La Grenouillère, which foregrounds the water and hosts a group of people as its background, evoking the lethargy of the afternoon and the warmth of the weather. The similar developments in both renditions of the same scene at La Grenouillère are quite obvious to the eye; and so is the individual style of the impressionist painters.

Forming Impressionist Aesthetics and Techniques

Renoir sums up the artistic deviation embarked upon by the Impressionist painters through this famous line: “One morning, one of us ran out of the black, it was the birth of Impressionism.”

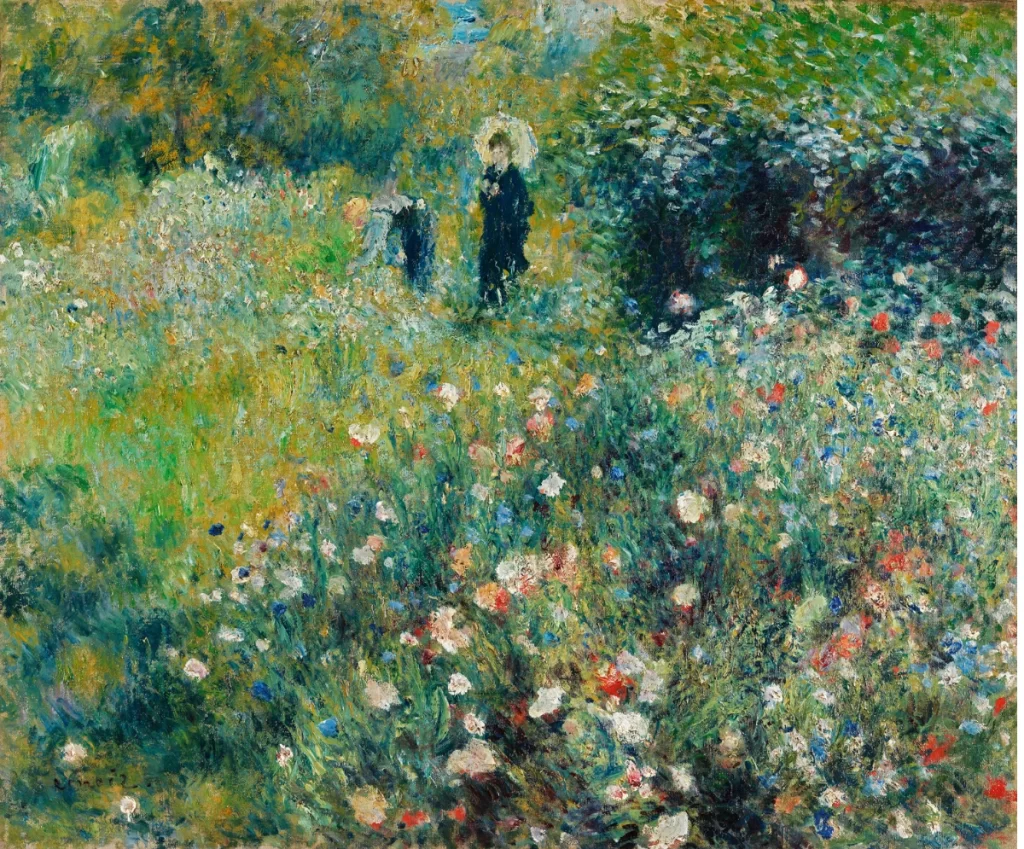

Renoir and other Impressionist artists left the closed space of the studio and chose to sit outdoors to paint directly from nature and what they could see. They changed the subject from the elevated portraits of the rich in their manicured gardens to the figures in public parks and the working people on the street. They wanted to capture the bare reality at its essence– the core of what constituted casual everyday life. Renoir himself focuses on this.

Courtesy – Wikipedia

I like painting best when it looks eternal without boasting about it: an everyday eternity, revealed on the street corner: a servant-girl pausing a moment as she scours a saucepan, and becoming a Juno on Olympus.

A great example of capturing this “everyday eternity” can be found in this painting of a servant girl, an example of Renoir and female portraiture.

Renoir moved away from firm and dark brushstrokes, delving into an ocean of bright loosely painted colours and quick brushstrokes. He started using impasto, a technique where undiluted paint is applied in thick visible layers on the canvas, to create a dimension of depth. Light came under crucial scrutiny by Renoir and other artists, as they tried to capture the natural reflections and the way light interacted with distinct objects. Most of Renoir’s famous paintings of this style are suffused with light, with a distinct exclusion of black. They sought to use other darker and variable colours to evoke the lights and shadows to characterise the composition.

Courtesy – Museo Thyssen

Renoir evolved his style consisting of broken brushstrokes, the use of impasto and bold combinations of colours that were purely complementary. He attempted to capture the flow of light in his paintings, creating a gentle suffused atmosphere. In the initial days, these techniques were criticised as French Impressionism art was viewed as sloppy and unfinished, displayed only in the Salon des Refuses, the show of the refused works, but they would soon go on to be one of the most sought-after artworks in the coming decades.

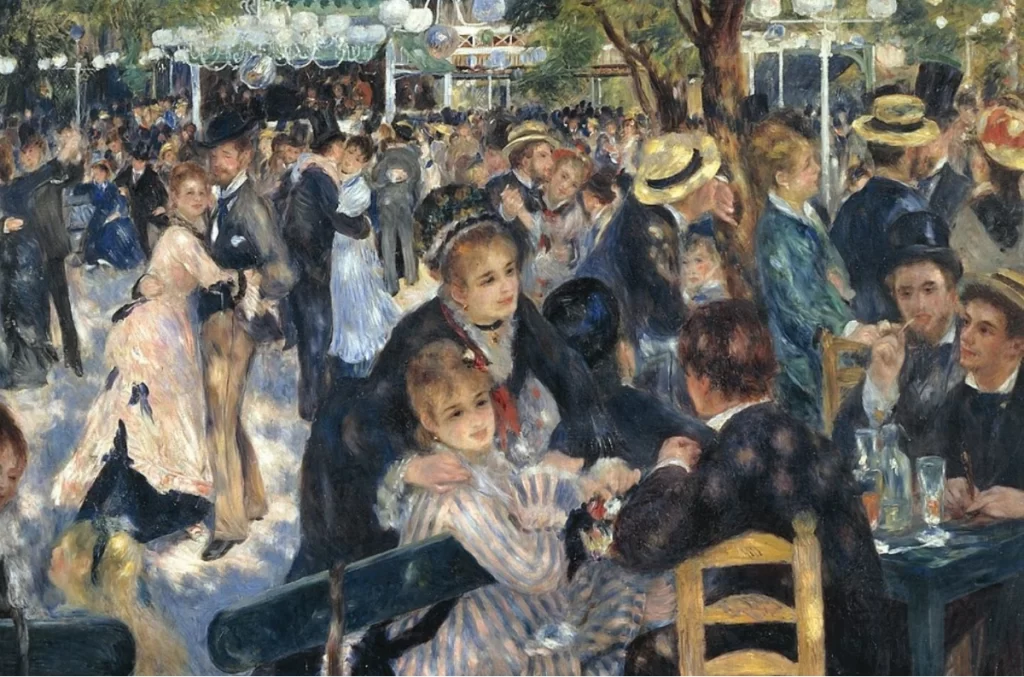

Dance at the Moulin de la Galette

One of Renoir’s famous paintings, Dance at the Moulin de la Galette (1876) remains his most well-known work that showcases the best of his techniques and reveals the absolute magic produced by his artwork. It was sold for an outrageous amount of $78.1 million in 1990, solidifying its place as one of Renoir’s most expensive pieces.

This French Impressionism art piece depicts the fleeting ephemerality of youth as Renoir paints a crowded scene at a popular dance garden on Butte Montmartre with his signature loose brushstrokes. Moulin is a compositional marvel as the painting encompasses over two dozen figures and yet avoids the sensation of overcrowding, with each subject in the composition holding a distinct place that isolates them from the rest.

Courtesy – Rise Art

Multiple groups of people can be separated compositionally in this painting, for example, there is a group in the foreground inlaid with yellow and gold tones that becomes the foundation of stability for the right side of the canvas. There is a sense of turbulence in the painting as the light flickers through the canopy and highlights different sections of the dance floor and people’s features.

Renoir’s Later Works

Renoir art style analysis during his later life depicts a drastic transformation and he started to focus on painting female nudes with big brushstrokes, focusing on reds and oranges. This tonal and aesthetic shift is not well appreciated in the art world, making Renoir one of the few artists whose works in his earlier period were valued more. Mary Cassatt, an American contemporary of Renoir, found his later work quite abominable, describing his subjects as “enormously fat red women with very small heads.” This latter work is also dissociated with the Impressionist painters, movement, and the annals of art history have pretty much written it out.

Courtesy – Meister Drucke

Eye For Beauty

Renoir emphasised certain aesthetics in his artworks and gave priority to capturing beauty. Perhaps this is why, even centuries later, even after the advent of neo-impressionism and post-modernism, there is a certain appeal to Renoir’s paintings. However, nobody can undermine the Post-Impressionism vs. Impressionism debates, which continue to this day.

Image – Les Grandes Baigneuses (The Large Bathers) (1887). Courtesy – Wikimedia Commons