Navratri history and significance

Navratri is Sanskrit for “nine nights,” a Hindu festival that honours the victory of good over evil and the divine female force, or Shakti, which is personified in the goddess Durga. All over the country of India it is celebrated on a massive scale, Hindus across the world too do observe Navratri however there are differences from region to region in terms of origin and customs. While Navratri is a religious festival, it holds cultural, social and artistic values as well. Based in the ancient Hindu mythology, the festival has changed over millennia under the influence of local practices, royal patronage and Vaishnavism philosophy.

Mythological Origins of Navratri

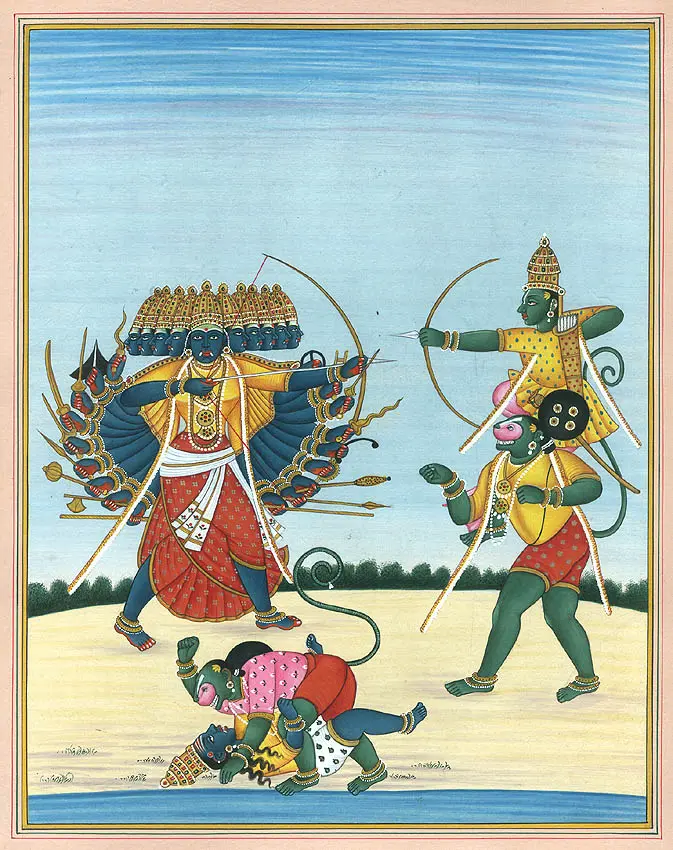

The mythology of Navratri is a fascinating one, full of legends and stories defining the essence. One of the most popular legends is that of battle between the goddess Durga and the demon king Mahishasura. Hindu Mythology describes Mahishasura as a very powerful demon who was given a boon by Lord Brahma that made him almost invincible, on the condition that he can be killed only by any women. Fuelled further by the belief in his own immortality, Mahishasura ran rampage across heaven and earth. With the gods incapable of stopping him, they called upon Durga–a ferocious form of Shakti. On the tenth day, Durga killed Mahishasura herself and saved the world from a great terror. The power of good over bad and the victory of feminine divine is represented in this win, so mother Durga is the central figure of Navratri.

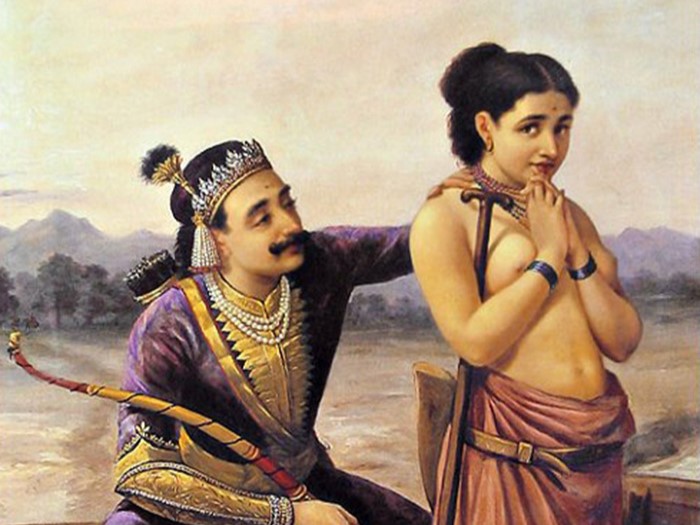

Another major Navratri myth is that from the Ramayana. It is said that the nine days were when Lord Rama worshipped Goddess Durga to seek her blessings before going on to fight Ravana, the demon king. Rama had defeated Ravana on the tenth day by that Mrakshika-Mukha nagara-dahan (burning an entire Lanka inside a single flame) to be exact, and it became a victory over evil, hence Vijayadashami or Dussehra. In this one, Navratri is the festival celebrating Rama’s devotion and righteous struggle against the demon king Ravana; propelled by fierce grace of Durga Maa – making it perfectly align with Dussehra celebrations majorly done in northern part of India.

Historical Development of Navratri

Although early Vedic references to Navratri are scarce, it has prehistoric roots. However, it seems that the roots of Navratri lie in a much older concept during the Vedic period — Shakti worship. The worship of Durga and other goddesses was slowly formalised over time, particularly in the medieval period when shakti cults emerged as significant social formations. The festival as we know it today is a sum of centuries-old devotional practices and rituals that adapted with the changes in society.

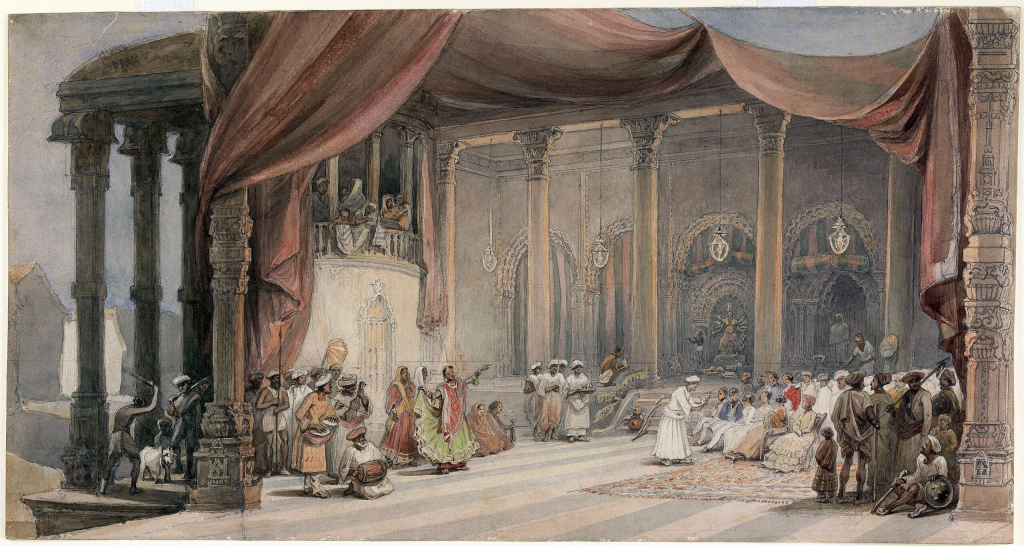

During the medieval era, Navratri achieved widespread significance with royal families playing a key role in propelling and enlargement of grandness to it. The festival loses its ownership of Durga Puja being Bengal where it became festive during the time around the Mughal Empire. This have been organised privately since the time of Maharanas and the first major one being debt by a Bengali Zamindar (landovers) or Royalty where Brahmins are invited for grand celebrations with Durga Puja in which it became religious-cultural festivity for community to gather together. The folk dance traditions of Garba and Dandiya have been popularised in the state of Gujarat, where this festival is celebrated with militants, and these ritual forms now remain indelibly associated with Navratri. These dances are dedicated to the Goddess — symbol of life, community and of course, the triumph of good over evil.

Even during the colonial era, where the British imposed upon us their own times customs and values, Navratri remained a testament of Indianness and spiritual resilience. The festival came to be an opportunity to express cultural pride, particularly in states such as West Bengal where Durga Puja was also transformed into a nationalist event, encouraging and supporting local traditions and insulate resistance from colonial influence.

Regional Variations in Celebrations

While all over India Navratri is celebrated widely, its rituals, customs and importance vary from region to region. The theme of the triumph of Durga over evil is common to all, but practices and rituals around Navratri are influenced by local cultures and histories.

So in case of East India (Durga Puja WestBengal, Assam and Odisha: A five day Navratri are synonymous with”Durga pujaparva”. The final five days of the festival reverberate with a heightened energy — statues of Durga crafted in elaborate detail are worshipped and carried in grand public processions. Bengal put up the grandest of art, music and dance for Durga Puja which was not just a religious but equally a cultural extravaganza. The festival ends with the immersion of Durga idols into water (such as a river), which signify the departure of Goddess Durga to her divine abode.

Western India (Garba and Dandiya): Navratri is a major festival in the Gujarati and Marathi community, where they perform Garba, or dance of clapping with joy along with Dandiya. These concentric circles symbolise the circular and eternal time. The dances are performed around a lamp or image of the goddess by men from rural, with them all clad in colourful traditional attire. Garba and Dandiya Raas done during the festival manifests the vibrancy of socialisation & enjoyment of Navratri.

Southern India (Golu and Saraswati Puja) : In southern states like Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh Navratri is performed by arranging Golu — a setup of dolls and figurines depicting mythological characters/scenes. The festivity also involves the worship of Saraswati, the goddess of learning in particular during the last three days of Navratri. This is the time by which children in Kerala are introduced to the alphabets and a ceremony called Vidyarambham goes on.

North India (Ramlila and Dussehra): In North India, Navratri is synonymous with the legends of Lord Rama in the epic Ramayana. The festival finishes on Dashami when, along with prayers to Ma Durga for her victory over Mahishasura, Ramlila concludes. The burning of effigies of Ravana, signifying the victory of good over evil, occurs on Vijayadashami or Dussehra. This day is also known as Durga Shakti Dikshanam and the victory of Durga over Mahishasura.

The Significance of the festival in Modern Times

In today’s India Navratri has evolved as cultural, spiritual and social time of year. It is not just a sacred festival, rather an affair of the community. art, and ancestry. It’s a time of rebirth for many — spiritually and personally. The nine days are considered a time for self-reflection, fasting, and devotion to duty ensuring that devotees regarding their potential are most valuable and virtuous.

Moreover, it also highlights the strength of feminine power and the significance of women’s empowerment as females play a crucial part in shaping society equally here the value of both masculine and feminine force. Music, Dance and Visual arts are also a significant part of the Navratri celebrations being elaborate forms of artistic expression. Navaratri is a festival stretching across 8–9 days all over India from the Garba nights in Gujarat to the Durga idols in Bengal itself and awakens creativity and community engagement.

Conclusion

Navratri is a festival with deep historical and mythological roots that transcends mere religious observance. It is a celebration of the victory of good over evil, the power of the feminine divine, and the importance of community and tradition. Over the centuries, Navratri has evolved, absorbing local customs and practices, and continues to be a dynamic expression of devotion, culture, and creativity in modern India. As it brings people together in joy and reverence, Navratri remains one of the most cherished festivals, reflecting the enduring values of Hindu culture and spirituality.

Feature Image Courtesy: gujarattourism