Introduction

The Indian miniature painting tradition boasts the opulent Mughal and Rajasthani ateliers adorned with gold; a practice rooted in Emperor Humayun’s importation of this revered Persian tradition. Following the Mughal and Rajasthani decline, skilled artisans dispersed across India, fostering thriving schools like Kangra and Basholi miniatures. Amidst these, the Assam School of manuscripts, now largely forgotten, emerged.

Assam’s painting evolution revolved around manuscript illustration, as noted in the Harsha Charita. Historical traces involve Agaru bark-based panels, brushes, and colour pots. The Phung Chin manuscript (1473 CE) and Suktanta Kyempong, reflecting Burmese influence, mark Assam’s earliest illustrations.

From the 16th century, Assam’s artistic prowess burgeoned, fueled by the neo-Vaishnavite movement catalyzed by Sankaradeva. This movement, championed by Sankaradeva’s biographies and the Katha-Guru-Charita, emphasized moral and spiritual growth via art forms like painting, drama, songs, dance, and music. Satras, promoting art and literature, bolstered this cultural resurgence, seen in the 1678 Bhagavata-purana copy.

During the 18th-century Ahom rule, Assam embraced the Mughal-inspired Court Style due to Mughal artists’ migration post-empire dissolution. This artistic shift, referred to as the Royal or Court Style, blossomed under Darrang’s patronage, with some works attributed to King Krishnarayana.

Intriguingly, Assam’s painting landscape also encompassed influences from Upper Burma’s Buddhist art. This offshoot, observed in Buddhist manuscripts and the Phung Chin manuscript, intertwined with Assam’s Vaishnavite school, forming the Tai-Ahom style.

In summary, Assam’s artistic journey burgeoned from manuscript illustrations rooted in Persia via Mughal and Rajasthani inspirations. Sankaradeva’s neo-Vaishnavite movement and the Ahom reign furthered Assam’s artistic heritage, giving rise to diverse styles such as the Royal and Tai-Ahom schools, though some like the Assam School of manuscripts have faded into obscurity.

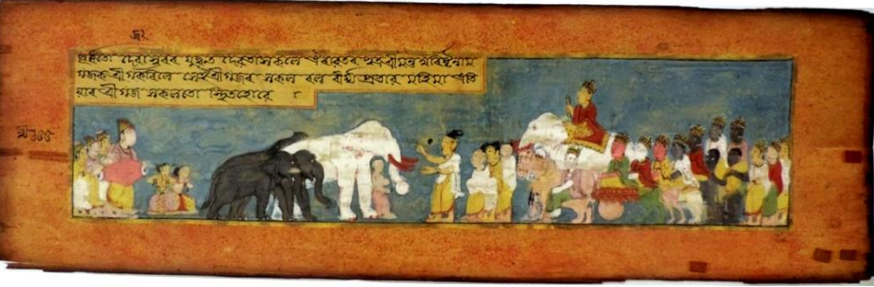

Title of the manuscript: Hastividyarnava, 1734 A.D. Courtesy: D.H.A.S. Government of Assam

Title of the manuscript: Hastividyarnava, 1734 A.D. Courtesy: D.H.A.S. Government of Assam

The Themes of the Illustrated Manuscripts

The Assamese manuscripts included illustrations of stories from the Bhagvata, the Puranas, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata that were mostly drawn as the supplement for the text that was to be written. There were also some manuscripts that depicted Manasa Devi, the goddess of snakes and these were wrapped with cobra skins.

The manuscripts did not restrict themselves to the religious content only, there were manuscripts on the chronicles of kings and were known as buranjis. Vamsavalis were manuscripts that provided information about the genealogical history of the family. There were independent volumes that were written dealing with the lives and achievements of prominent religious reformers and saints, both male and female, which were known as charitra puthis. here are even some like the Hasti-vidyarnava and Ghora-Nidana that is a treatises on elephants and a study on horses, respectively.

The Materials and Methods Involved in Making the Manuscripts:

The manuscript’s foundation was meticulously crafted from the bark of the Aquilaria agallocha tree, also known as the Sanchi tree, Agaru tree, or agar tree. This material, locally termed Sanchipat, was an essential medium in Assam’s artistic tradition. The intricate process of preparing Sanchipat involved a series of labour-intensive steps, beginning with the careful selection of aloe bark and culminating in a polished surface ready for artistic creation.

In Assam, the favoured aloe bark is derived from the rapidly growing Sanchi tree, specifically categorized as ‘Bhola Sanchi.’ Another variety, known as Jati Sanchi or Jatiya Sanchi, exhibited distinctive characteristics like natural holes caused by insect activity. The smoother texture of Bhola Sanchi bark made it preferable for artisans and scribes, likely contributing to the preference for fine and flowing lines in the manuscript illustrations.

Aquilaria tree or Sanchi tree (Bhola Sanchi), Courtesy: Chittaranjan Bora, Purani Gudam, Nagaon, Assam (India)

Aquilaria tree or Sanchi tree (Bhola Sanchi), Courtesy: Chittaranjan Bora, Purani Gudam, Nagaon, Assam (India)

The traditional Sanchipat preparation commenced with the meticulous selection of a fifteen-to sixteen-year-old Bhola Sanchi tree with specific dimensions. This choice was crucial to ensure a supple and smooth surface conducive to artistic manipulation. A bark segment measuring six to eighteen feet in length and three to twenty-seven inches in width was then carefully extracted from a specific region about four feet above the ground, chosen for its suitability to the intended process. This section’s thickness, quality, and fibre maturity played a pivotal role in crafting high-quality Sanchipat.

After stripping the bark, it was meticulously rolled with the inner side exposed to sunlight, facilitating swift drying of the moisture-laden white surface. Dew played a vital role in minimizing moisture content, aiding the separation of the remaining layer, known as ‘nikari.’ Subsequently, the bark was methodically sectioned into pieces, with the size contingent on the artist or Khanikar’s requirements and the intended artistic endeavours.

Removed Sanchi Bark, Courtesy: Assam State Museum, Guwahati, Assam (India)

Removed Sanchi Bark, Courtesy: Assam State Museum, Guwahati, Assam (India)

In essence, the intricate art of crafting Sanchipat manuscripts originated from the bark of the Aquilaria agallocha tree, a material deeply rooted in Assam’s creative heritage. The elaborate process, from Bhola Sanchi tree selection to precise bark extraction and conditioning, reflected the dedication and skill intrinsic to this traditional artistic practice.

The Present-day scenario of the Manuscript Making Process

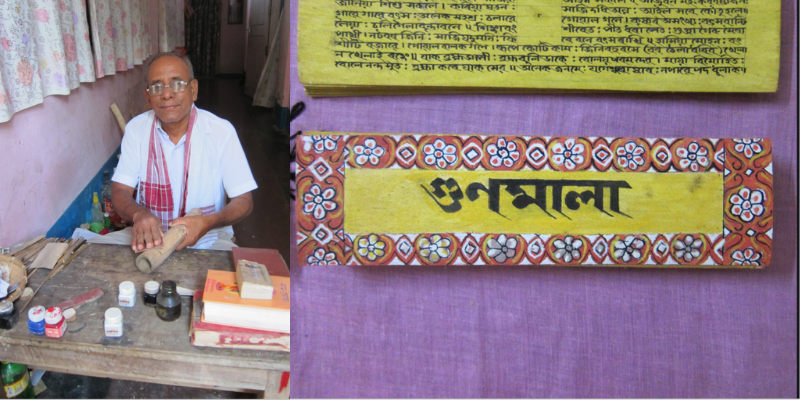

In the present-day scenario of the Assam School of manuscript, paintings are in a dilapidated state and only restricted to specific satras of the state. Artist Hari Narayan Konwar is one such manuscript artist who is taking the heritage of painting manuscripts to the present day. To this day at his house in Nagaon, Assam, the artist is very keen to showcase his talent for the making of the manuscript following the footsteps of his ancestors and painting on the Sanchi barks.

Artist Hari Narayan Konwar at his home with a Sanchi manuscript. Photography by: Meghna Barua for Sahapedia

Artist Hari Narayan Konwar at his home with a Sanchi manuscript. Photography by: Meghna Barua for Sahapedia

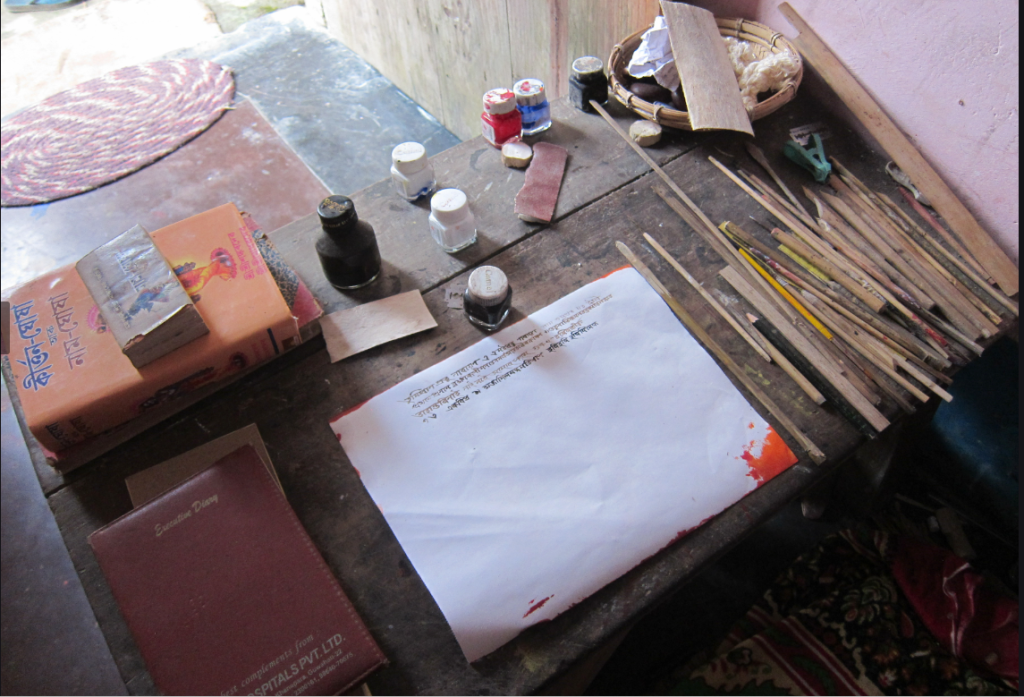

The different kinds of pencils required for making the manuscript were drafted from bamboo by the artist himself. Photography by: Meghna Barua for Sahapedia

The different kinds of pencils required for making the manuscript were drafted from bamboo by the artist himself. Photography by: Meghna Barua for Sahapedia

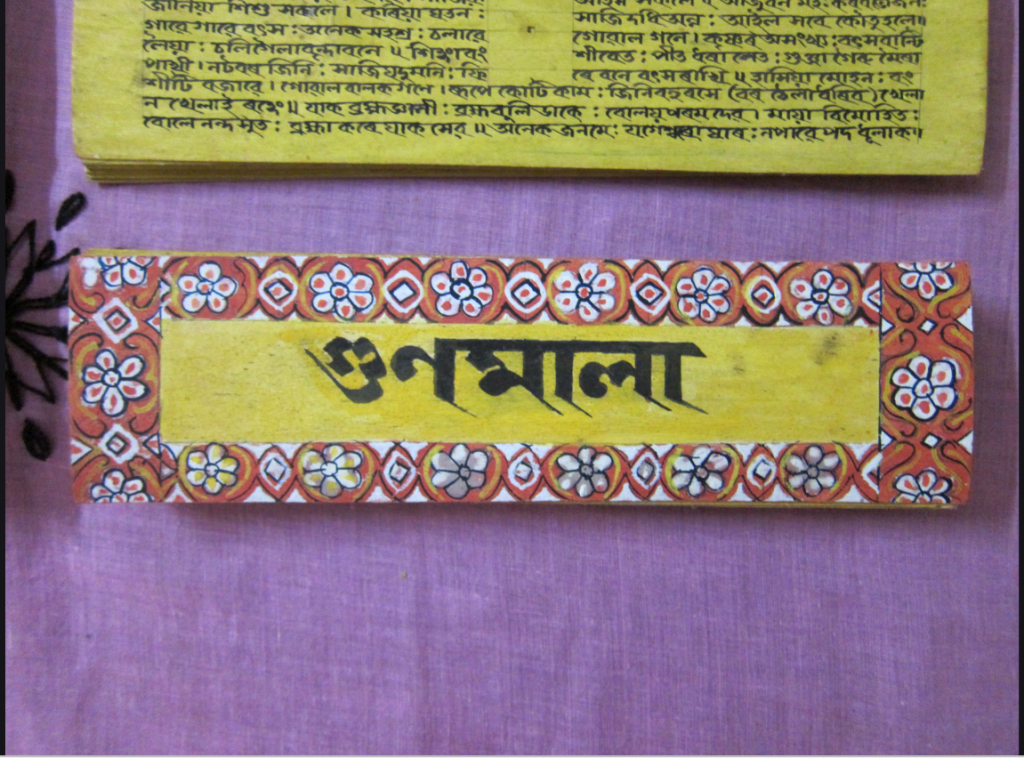

The Manuscript of ‘Gunimala’ painted by Artist Hari Narayan Konwar on Sanchi bark. Photography by Meghna Barua for Sahapedia

The Manuscript of ‘Gunimala’ painted by Artist Hari Narayan Konwar on Sanchi bark. Photography by Meghna Barua for Sahapedia

In conclusion, the manuscript-making process in the traditional setting of Assam is a tiresome process. With the advent of technology and all things available within the reach of a button, there are artisans still today striving out of their way to save this glorious and lost tradition. The painting process is now only restricted to the various satras or religious institutions across Assam. Some of the earliest manuscript paintings are in the collection of the Assam State Museum, Guwahati.

Contributor