Ved Prakash Bhardwaj

‘’I began exploring the visual form of ink drawings to express my own experience of displacement that made me lose my home in Jaffna.’’

-Jasmine Nilani Joseph

Young Sri Lankan artist Jasmine Nilani Joseph’s exhibition titled, “The Sixth Diary”, running at Vadehra Art Gallery, Delhi, presents a new vision of a young girl’s dreams, the pain of people displaced by the civil war, and the hope of life amidst so many disparities. Jasmine Nilani Joseph won the Asia Society Art Game Changer Awards India in 2022. Her work consists of drawings, hybrid sculptures, and animated movies. Joseph illustrates the personal and historical meeting point in her much anticipated solo exhibition, The Sixth Diary, and provides a narrative of events from her perspective as the youngest and sixth child in her family. The Sixth Diary provides a new and emotive perspective by enduring and experimenting with drawing, transforming journalistic research to the self into a priceless repository of the contextual natures of a person.

Jasmine, a resident of Jaffna, Sri Lanka, lived with her parents and siblings in a refugee camp in the town of Vavuniya during the three-decade-long civil war and then settled there as part of a housing scheme project. These experiences established a new vision of personal and public life. She returns to Jaffna to pursue her art, where being alone in the city of her ancestors fills her with melancholy and anxiety. Heritage in the form of memories seems to be hiding itself today in the face of current chaos and apprehension of future crises.

Since Joseph is separated from her family and her ideal home, as well as from her ingrained ideas of belonging and celebration from before the dislocation, her solo movements also reflect generational separation in the geographical isolation of Jaffna. These difficult situations have served as the backdrop for deep and significant insights into how the concept of family grows and endures in the face of trauma, dislocation, and distance. By combining temporality and site-specificity, she presents communal traumas as an assemblage of personal histories, making space into a dynamic, politicized extension of the bodies that either currently or absently comprise it. This intensifies such contextual parameters of individual identity. Joseph’s tales are also superseded by conceptions of mobility, including how concepts such as thoughts, images, or objects move, how motion may be represented, and how movements can be investigated as a part of shared temporality and physical history. Joseph’s narratives dismantle history as a source of various experiences and truths in the present by addressing collectivism through fragmentation.

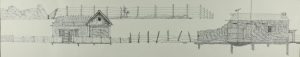

Joseph is an expert draughtsman; her mark-making combines meditative pointillism with acute linearity to create charged images of environments that are then juxtaposed against calming neutrality. Her compositions have a distinct linearity that stems from a conceptual understanding of the fence as a symbol of connection and separatism. The animated protrusion of the fence operates within the inside-outside dialectic, maintaining the cognitive and physical division of spaces while also bringing their apparent endlessness into the mix. For Joseph, the fence is both a physical object that serves as a symbol of his place in the world and a figment of his imagination. The fence’s metaphorical meaning suggests that it is a barrier that must be surmounted by a person’s progress as an individual or by the culture and tradition in which they live.

Her work emphasizes the textuality of drawing as a means of expressing abstract concepts by using surface contouring as the main incision and strengthening the capacity to record sense. Joseph continues to investigate the structure as an expression of the human soul by unintentionally working within the diagrammatic traditions of Sri Lankan architecture, where regional, climate-based adaptations of Western construction are portrayed in linear patterns bringing nature closer to home. She gives diary-like examples of habitation while politicizing the concept of home by describing the relationships between architectural forms and their environment. However, Joseph’s story compositions remain profoundly personal at their core. She somehow returns to the family and home as ideal notions that transcend their physical envelopment and may be welcomed voluntarily and wholeheartedly through re-orientations, despite the extreme misery she endured in her early existence.