Since the MeToo Movement began, the misogyny of many ‘legends’ has come into focus, especially in the arts—literature, cinema, the visual arts and even comedy. An important question that is being asked, again and again, is whether we can, in fact, separate the art from the artist.

The first time I stood in front of the cubists’ work was at Its Pablo-matic: Picasso According to Hannah Gadsby exhibition, at the Brooklyn Museum. Perhaps that alone would have been enough to write about. However, it was viewing 50 of his works with witty commentaries by Gadsby herself, alongside 49 pieces by contemporary feminist artists that made the show noteworthy.

In her 2018 Netflix special Nannette, Gadsby talked extensively about Picasso. Here is an excerpt:

Pablo Picasso. I hate him, but you’re not allowed to. But you can’t…Cubism. And if you ruin Cubism then civilisation as we know it will crumble. Aren’t we grateful…that we live in a post-cubism world?

And I know I should be more generous about him too because he suffered a mental illness. But you see nobody knows that. Because it doesn’t fit with his mythology. Because Picasso, he’s sold to us as this passionate, virile, tormented genius, man, ballsack, right? But he did suffer a mental illness. Picasso did. He suffered badly and it got worse as he got older. Picasso suffered from the mental illness of misogyny. (CROWD LAUGHS)

Is misogyny a mental illness? Yeah. Yeah, it is! Especially if you’re a heterosexual man. Because if you hate what you desire, do you know what that is? Fucking tense.

It is clear that’s where the conception of this show originates. Its Pablo-Matic looks at the icon’s complicated legacy through a critical, contemporary, and feminist lens. As Catherine Morris, the senior curator at the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art said in an interview, “It’s an experiment in how to make a museum show with a more conversational voice.” The show is designed such that it feels like Gadsby is showing you around, making you see Picasso in his pieces.

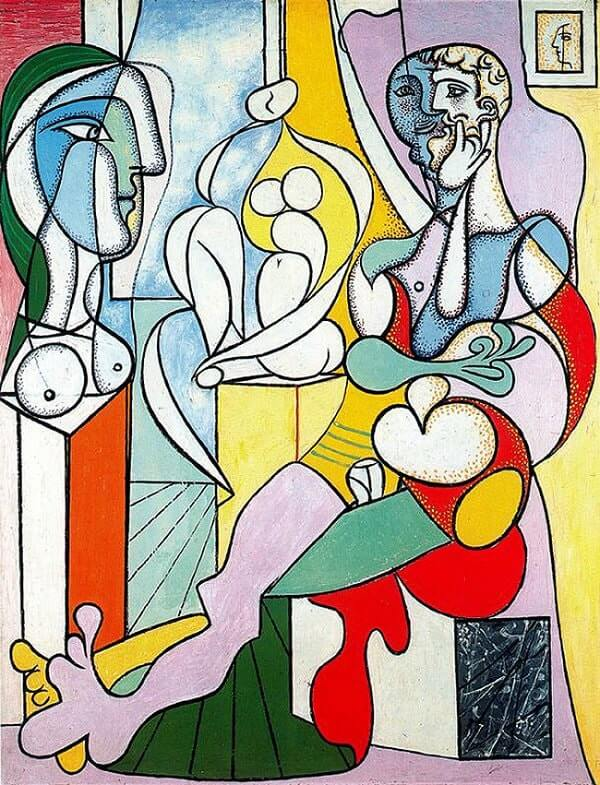

As you enter the gallery, the first piece by Picasso you see is The Sculptor (1931). In the piece, you see a sculptor — probably Picasso himself—with a bust of a woman looking down at the sculptor. In the background, you see a female nude figure. Next to it was a description by Gadsby:

I would like to draw your attention to the figure on the left-hand side of this image. I invite you to scan from her breasts up to her mid-cheek. Notice anything? That’s right . . . that there is a cock and balls. One of seven hidden within the composition. Is it fair to ask me to separate the man from his art when he couldn’t even separate himself from his art in his art? Asking for a friend.

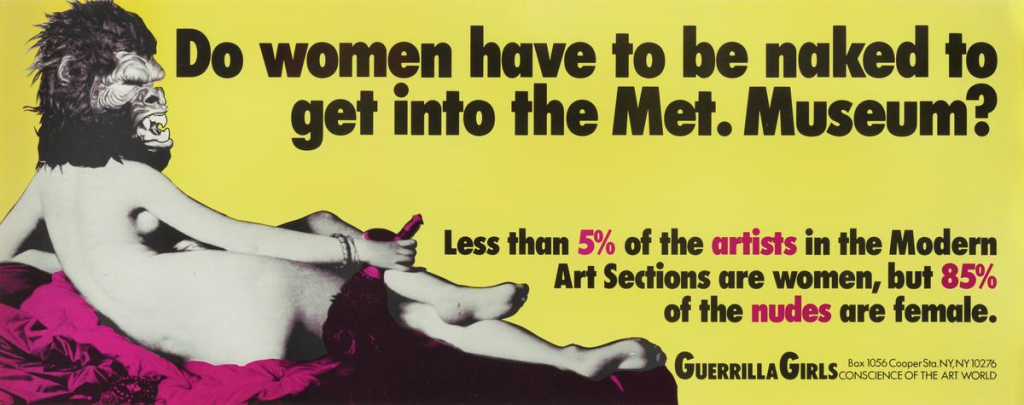

I looked at the Sculpture again and all I could see were the now visible male genitalia. On a wall to its right was the piece by Guerrilla Girls titled Do Women Have To Be Naked To Get Into the Met Museum?

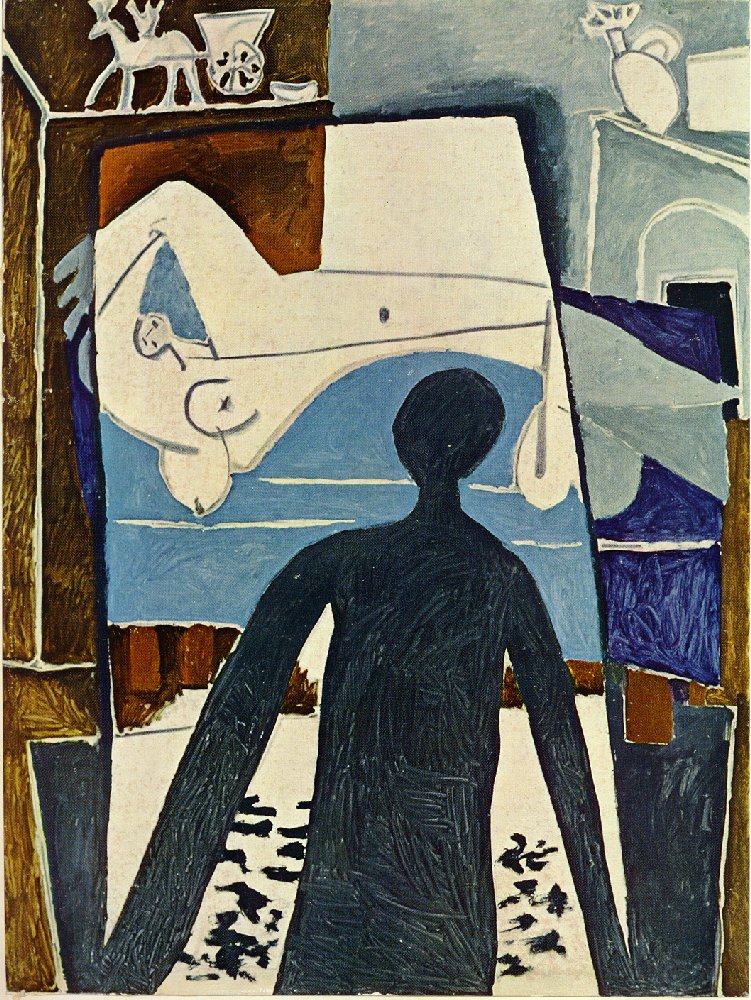

One of the more disturbing paintings by Picasso, also one of the most famous, on display was The Shadow (1953). It shows the shadow of a man looking into a window, where a naked woman lays asleep on a bed, unaware of being observed. It’s a self-portrait, Picasso being the shadow. The composition makes the viewer share Picasso’s vantage point; the viewer steps in the shoes of the voyeuristic shadow; voyeuristic Picasso. It’s a deeply uncomfortable painting, especially after learning that Picasso made this work after his partner Francoise Gilot had left him.

In contrast, stood Intimacy-Autonomy (1974) by Joan Semmel. It captures a post-coital moment between a man and a woman. Instead of continuing the tradition of representing headless nudes without identities, Semmel positions the viewer at the figures’ heads. The bodies thus become our own. It is a very tender painting. Interestingly, it was one of the works I observed being photographed by men the most, accompanied by their adolescent laughter, its tenderness clearly lost to them.

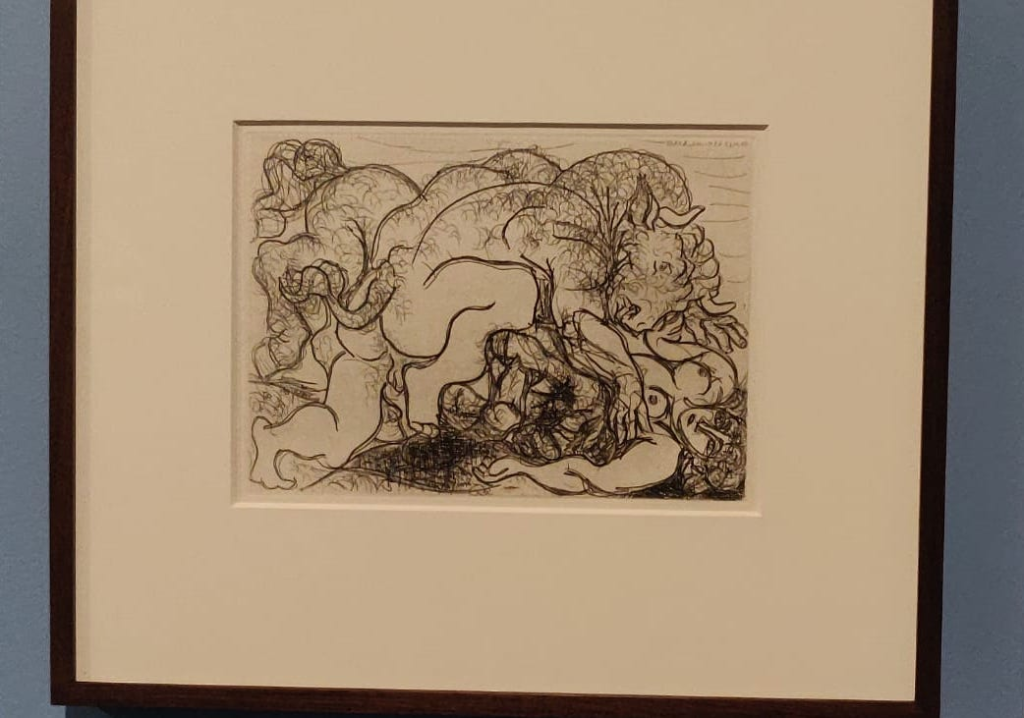

Several of Picasso’s works from the 1930s were also on display. Picasso drew the prints for art dealer Ambroise Vollard, exploring themes of male sexuality, ambition, obsession, fear, and morality. A primary figure in most of these works was the half-man-half-animal creature the minotaur. It serves as Picasso’s alter ego, symbolising his conflicted inner forces of brutality and rationality. These are some of the most sexually graphic works on display, the brutality too obvious to ignore. One of these works is quite literally titled Minotaur Raping a Woman (1933). The woman in these prints resembles Marie-Thérèse Walter, the 17-year-old Picasso was in a relationship with when he was 46.

The show engages with Picasso by acknowledging his life, his relationships, his muses and artistic practices that inspired him and in turn cubism itself. Part of the exhibit also explored the role played by Indigenous Art from Africa and Australia, previously called primitive.

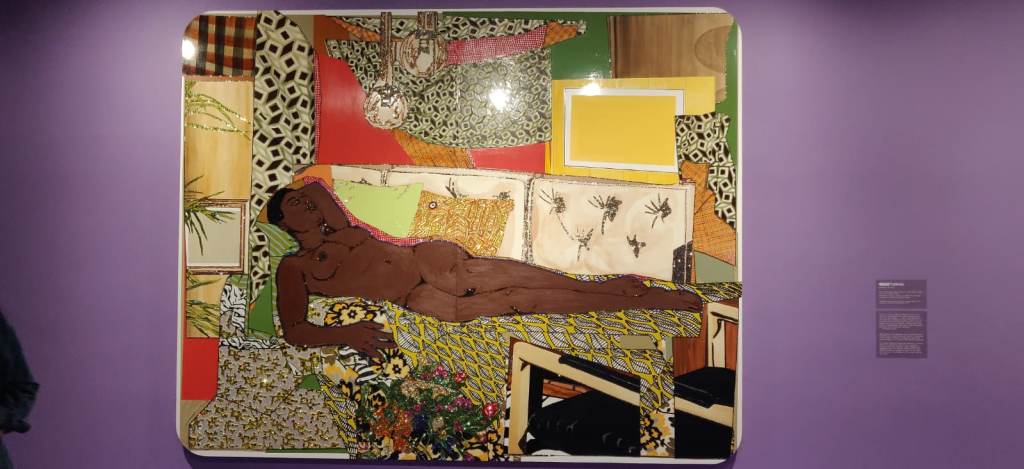

One of the works on display is Marie: Nude Black Woman Lying on a Couch (2012) by Mickalene Thomas. It is a piece of work in response to Picasso’s reclining women (and that of other modern artists’). Thomas’s reclining nude adds Black female autonomy to the role of both painter and sitter.

The show has received a lot of criticism; The New York Times art critic Jason Farago wrote that he left the show feeling “sad and embarrassed” and the Artnews review called the show “disastrous.”

Being dismissive of the works of men like Picasso is a lazy stance to have; one cannot deny their brilliance and impact on culture. However, to not think critically of their work in the world they now exist in, is a lazy act too. The focus of It’s Pablo-matic is on how Picasso’s real-life connections with women are crucial for evaluating his art because he frequently portrayed sex, women, and himself, in his works.

Clearly, there is a need to have meaningful ways to engage with such work, with a lens that is empathic and accounts for the nuanced. Its Pablo-matic attempts that. At the least, the show pushes the conversation forward. As the co-curator Catherine Morris said in a podcast that the show is about “giving complicated things the space to be complicated.”

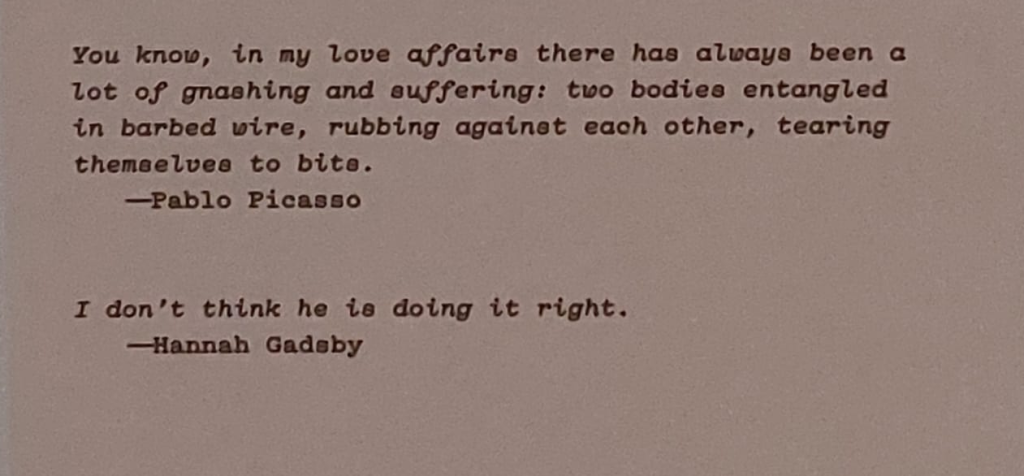

My favourite moment was chuckling with a fellow female viewer, reading this commentary by Hannah Gadsby:

Picture Courtesy: Os Tyagi.

It’s Pablo-matic: Picasso According to Hannah Gadsby is curated by Hannah Gadsby; Catherine Morris, Sackler Senior Curator, Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art; and Lisa Small, Senior Curator, European Art; with Talia Shiroma, Curatorial Assistant, Arts of the Americas and Europe, Brooklyn Museum. This exhibition is organised by the Brooklyn Museum in collaboration with the Musée National Picasso-Paris and is part of a global presentation of exhibitions and events marking the fiftieth anniversary of Pablo Picasso’s death.

Read Also:

Negative reviews of Hannah Gadsby’s “Pablo-matic” Show Dismissed by Brooklyn Museum