Kritika Verma

This long-read-research article about Street Art- Graffiti in the Indian context brings multi-layer ideas about social life and street art as a context itself. Read the first part of this research article here: Street Art and Graffiti In Indian Public Spaces. Read the Second article: Historical Background of Graffiti and Street Art in India.

Slogans of protest and political or social commentary graffiti on walls are the precursor to modern graffiti and street art and continue as one genre aspect. Street art in text or simple iconic graphics of corporate icons can become well-known yet enigmatic symbols of an area or an era. Some credit the Kilroy Was Here graffiti of the World War II era as an early example; a simple line drawing of a long-nosed man peering from behind a ledge. Author Charles Panati indirectly touched upon the general appeal of street art in his description of the “Kilroy” graffiti as “outrageous not for what it said, but where it turned up”. Much of what can now be defined as modern street art has well-documented origins dating from New York City’s graffiti boom, with its infancy in the 1960s, maturation in the 1970s, and peaking with the spray-painted full-car subway train, murals of the 1980s centred in the Bronx.

As the 1980s progressed, a shift occurred from text-based works of early in the decade to visually conceptual street art, such as Hambleton’s shadow figures. This period coincides with Keith Haring’s subway advertisement subversions and Jean-Michel Basquiat’s SAMO tags. What is now recognized as “street art” had yet to become a realistic career consideration, and offshoots such as stencil graffiti were in their infancy. Wheatpasted poster art used to promote bands and the clubs where they performed evolved into actual artwork or copy art and became a common sight during the 1980s in cities worldwide. The group working collectively as AVANT was also active in New York during this period. Punk rock music’s subversive ideologies were also instrumental to street art’s evolution as an art form during the 1980s. Some of the anti-museum mentality can be attributed to the ideology of Marinetti, who in 1909 wrote the “Manifesto of Futurism” with a quote that reads, “We will destroy all the museums.” Many street artists claim we do not live in a museum, so art should be in public with no tickets.

Early iconic works

The northwest wall of the intersection at Houston Street and the Bowery in New York City has been a target of artists since the 1970s. The site, sometimes called the Bower Mural, originated as a derelict wall that graffiti artists used freely. Keith Haring once commandeered the wall for his use in 1982. After Haring, a stream of well-known street artists followed until the wall gradually became prestigious. By 2008, the division became privately managed and made available to artists by commission or invitation only.

A series of murals by René Moncada began appearing on the streets of SoHo in the late 1970s, emblazoned with the words I AM THE BEST ARTIST. René has described the murals as a thumb in the nose to the art community he felt he had helped pioneer but by which he later felt ignored. Recognized as an early act of “art provocation”, they were a topic of conversation and debate at the time; related legal conflicts raised discussion about intellectual property, artists’ rights and the First Amendment. The ubiquitous murals also became a famous backdrop t photographs taken by tourists and art students, as well as for advertising layouts and Hollywood films. IATBA murals were often defaced, only to be repainted by René.

Franco the Great, also known as the “Picasso of Harlem”, is another world-famous street artist internationally known for his New Art form. There were riots in the streets when Martin Luther King, Jr. was slain in 1968. Harlem business owners retaliated by installing drab-looking metal gates on their storefronts. Franco decided to turn a negative into a positive by developing a new art form on the steel gates in 1978. On Sundays, he has painted over 200 gates from the west to the east side of 125th street since then, when stores are closed.” 125th Street in Harlem is known as “Franco’s Blvd” because of his magnificent paintings on the metal business gates.

Commercial Crossover

Some street artists have earned international attention for their work and have made a complete transition from street art into the mainstream art world — some while continuing to produce art on the streets. Keith Haring was among the earliest wave of street artists in the 1980s to do so. Traditional graffiti and street art motifs have also increasingly been incorporated into mainstream advertising, with many instances of artists contracted to work as graphic designers for corporations. Graffiti artist Haze has provided font and graphic designs for music acts such as the Beastie Boys and Public Enemy. A special commission for use in the presidential campaign reworked Shepard Fairey’s street posters of then-presidential candidate Barack Obama. A version of the artwork also appeared on the cover of Time magazine. It is also not uncommon for street artists to start their merchandising lines.

Street art has received artistic recognition with the high-profile status of Banksy and other artists. This has made street art one of the ‘sights to see’ in many European cities. Some artists now provide tours of local street art and can share their knowledge, explaining the ideas behind many works, the reasons for tagging, and the messages portrayed in many graffiti works. Berlin, London, Paris, Hamburg and other cities have popular street art tours all year round. In London alone, there are supposedly ten different graffiti tours for tourists. Many of these organizations, such as Alternative London, Paris Street Art, and Alternative Berlin, pride themselves on working with local artists so that visitors can get an authentic experience and not just a rehearsed script.

This long-read-research article about Street Art- Graffiti in the Indian context brings multi-layer ideas about social life and street art as a context itself. Read the first part of this research article here: Street Art and Graffiti In Indian Public Spaces. Read the Second article: Historical Background of Graffiti and Street Art in India.

Many of these guides are painters, fine-art graduates and other creative professionals who have found street art as a way to exhibit their work. With this commercial angle, they can let people into the world of street art and give them more of an understanding of where it comes from. It has been argued that this growing popularity of street art has made it a factor in gentrification.

Legality and ethics

Street art can have legal problems. The parties involved include the artist, the city or municipal government, the intended recipient, the structure’s owner, or the medium where the work was displayed. One example is a case in 2014 in Bristol, England, which illustrates the legal, moral and ethical questions that can occur. The Mobile Lovers by Banksy was painted on plywood on a public doorway, then cut out by a citizen who, in turn, would sell the piece to garner funds for a boys’ club. The city government, in turn, confiscated the artwork and placed it in a museum. Hearing of the problem, Banksy bequeathed it to the original citizen, thinking his intentions were genuine. In this case, as in others, the controversy of ownership and public property, as well as the issues of trespassing and vandalism, are issues to be resolved legally.

Copyright

Under United States law, street artworks should be able to find copyright protection as long as they are legally installed and can fulfil two additional conditions; originality in the creation and fixed in a tangible medium. This copyright would then survive for the artist’s lifespan plus 70 years. If there is a collaboration between two artists, both will hold joint ownership of the copyright. Street artists also have moral rights in their work, independent of economic rights from copyright. These include the right to integrity and the right to attribution. Recently, street art has started to gain recognition among art critics, and some major companies have found themselves in trouble for using this art without permission for advertising. In such a case, H&M, a fast fashion retailer, used street art by Jason “Revok” Williams in an advertisement series. In response to Williams’ ‘Cease’ notice, however, H&M filed a lawsuit, alleging that since the work is a “product of criminal conduct”, it cannot be protected by copyright. This view has been taken earlier, too, in the cases of Villa v. Pearson Education and Moschino and Jeremy Tierney. In all three cases, settlements were reached before the judge could make a ruling on the issue of the illegality of the art. These companies typically settle out of court to avoid costly, time-consuming litigation.

Regarding the destruction of street art, the United States has applied the Visual Artist’s Right Act (VARA) to introduce moral rights into copyright law. In English v. BFC & R East 11th Street LLC and Pollara v. Seymour, it was held that this Act was inapplicable to works of art placed illicitly. A distinction was also made between the removable and nonremovable pieces, indicating that if a work can be removed trivially, it cannot be destroyed, irrespective of its legal status. Another important factor considered by the court in the latter case was whether the artwork was “of a recognized stature”.

In a case where a group of artists was awarded $6.7 million, the judge held that the art was not made without permission of the owner of the building and that an important factor was that the demolition was done ahead of the intended date, indicating willful thought.

Consumer protection laws

The rights of consumers in India are protected by the Consumer Protection Act 2019 (COPRA). Art dealers, auction houses, art galleries and online art sellers will be liable for selling defective goods under the COPRA. They may also be sued for deficiency in their services of providing good services. A ‘defect’ under the COPRA encompasses: any fault, imperfection or shortcoming in the quality, quantity, potency, purity or standard which is required to be maintained by or under any law for the time being in force or under any contract, express or implied or as is claimed by the trader in any manner whatsoever about any goods or product and the expression ‘defective’ shall be construed accordingly.

Further, ‘deficiency’ includes any shortcoming, negligence, omission or deliberate holding back of critical information by a service provider, which may amount to lose to the person seeking their service. Therefore, a buyer who seeks the assistance of an art dealer, art gallery, auction house or online art platform for buying art will be entitled to a remedy under the COPRA.

Street Art, guerrilla art and Graffiti

This long-read-research article about Street Art- Graffiti in the Indian context brings multi-layer ideas about social life and street art as a context itself. Read the first part of this research article here: Street Art and Graffiti In Indian Public Spaces. Read the Second article: Historical Background of Graffiti and Street Art in India.

Graffiti is characteristically made up of written words meant to represent a group or community in a covert way and plain sight. The telltale sign of street art is that it usually includes images, illustrations, or symbols that are meant to convey a message. While both works represent or tell a message to viewers, one difference between them comes in the specific viewers it is meant for. One trait of street art that has helped to bring it to positive light in the public eye is that the messages shown are usually made to be understandable to all.

While both types of art have many differences, there are more similarities than their origins. Graffiti and street art are works of art created with the same intent. Most artists, whether working anonymously, creating an intentionally incomprehensible message, or fighting for some more significant cause, are working with the same ambitions for popularity, recognition and the public display or outpouring their thoughts, feelings and passions.

Street art is described in many different ways, one of which is “guerrilla art”. Both words describe these public works that are placed with meaning and intent. They can be done anonymously for works created to confront taboo issues that will result in a backlash or under the name of a well-known artist. With any terminology, these works of art are created as a primary way to express the artist’s thoughts on many topics and issues.

As with Graffiti, an initial trait or feature of street art is that it is often created on or in a public area without or without the owner’s permission. A primary distinction between the two comes in the second trait of street art or guerrilla art, which is made to represent and display a purposefully uncompliant act meant to challenge its surrounding environment. This challenge can be granular, focusing on issues within the community or broadly sweeping, addressing global issues on a public stage.

This is how “guerrilla art” was associated with this work and behaviour. The word ties back to guerrilla warfare in history, where attacks are made wildly, without control and rules of engagement. This type of warfare dramatically differed from the previously formal and traditional fighting that went on in wars usually. When used in the context of street art, the term guerilla art is meant to give the nod to the artist’s uncontrolled, unexpected and often unnamed attack on societal structure or norms.

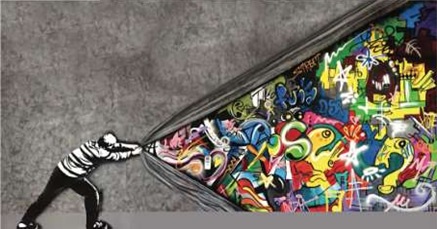

Some have asked if it is sufficient to place art in the street to make street art; Nicholas Riggle looks more critically at the border between graffiti and street art and states that “an artwork is street art if – and only if – its material use of the street is internal to its meaning”. The street is not a blank canvas for the street artist. It has a character, a use, a history, a texture, and a shape. Street art, as well as broader urban art, transforms the street or opens the dialogue. Justin Armstrong states graffiti is identified as an aesthetic occupation of spaces, whereas urban street art repurposes them.

Public acceptance

Although street art may be ubiquitous around the world, the popularity of its artistic expression is relatively recent. Street art has significantly transformed public opinion to become socially accepted and respected in some public places. Despite this acceptance, defacing private or public property with any message, whether considered art or not, is still widely illegal.

Initially, graffiti was the only form of street art, and it was widely considered a delinquent act of territorial marking and crude messaging. Initially, there were apparent divisions between the work of a street artist and the act of tagging public or private property. Still, in recent years where the artists are treading the line between the two, this line has become increasingly blurred.96 Those who genuinely appreciate the work of famed street artists or street works of art accept that this art would not be the same without the medium being the street. The pieces are subject to whatever change or destruction may come because they are created on public or private surfaces which are neither owned by the artist nor permitted to be worked on by the property owners. This acceptance of the potential impermanence of the works of art and the public placement of the unconditioned results contribute to the meaning of the piece and, therefore, what helps the growth of street art popularity.

Perhaps contrary to some street artists’ earlier anti-museum and ticket sale sentiments, a dedicated exhibition to Street Art under the title ‘Urban’ opened in Peterborough Museum, United Kingdom, on the 11th of December 2021. Tickets for the preview evening are selling at £5 GDP; subsequent entry is charged at £8 per person. The exhibition has been promoted as being of ‘major national [UK] importance’ and celebrating artists such as Banksy, Damien Hirst, My Dog Sighs, the Connor Brothers, Pure Evil and Blek le Rat. At the same time, street art and sculpture have been displayed at Bristol Museum since Banksy’s’ takeover’ in 2009.

Beautification Movement

Given the various benefits and sometimes high return on investment, street art provides businesses, schools, neighbourhoods and cities with a movement as a tool to create safer, brighter, more colourful and inspiring communities. This trend has recently been more widely recognized. Organizations like Beautify Earth have pioneered cities to leverage these benefits to create widespread beauty where it would be otherwise empty or dilapidated public wall space.

Asia- India

In India, street art is hugely popular. Many of the film and TV series promotional materials were created by street painters/artists. Currently, digital art is replacing hand-painted posters. From 1960 to the 1990s, street posters worked well and impressed audiences. In the 1990s, hand-painted signs started to be replaced by flex banners outside theatres. After the 2000s, street posters’ popularity declined, replaced by digitally printed posters. Street art painting and drawing sketches have since fallen in India due to the replacement of digital signs.

Malaysia

In George Town, Penang, Lithuanian artist Ernest Zacharevic created a series of murals depicting local culture, inhabitants and lifestyles. They now stand as celebrated cultural landmarks of George Town, with Children on a Bicycle becoming one of the most photographed spots in the city. Since then, the street art scene has blossomed.

South Korea

In South Korea’s second-largest city, Busan, German painter Hendrik Beikirch created a mural over 70 metres (230 ft) high, considered Asia’s tallest at its creation in August 2012. The monochromatic mural portrays a fisherman. Public Delivery organized it.

United Arab Emirates

In United Arab Emirates’ largest city, Dubai, several famous painters created urban mural artwork on the buildings, initiated by StreetArtNews and named Dubai Street Museum.

Exhibitions, festivals and conferences

In 1981, Washington Project for the Arts held a Street Works exhibition, which included urban art pioneers such as Fab Five Freddy and Lee Quiñones working directly on the streets.

Sarasota Chalk Festival was founded in 2007, sponsoring street art by artists initially invited from throughout the US and soon extended internationally. In 2011 the festival introduced a Going Vertical mural program and its Cellograph project to accompany the street drawings created by renowned artists worldwide. Many international films have been produced by and about artists who have participated in the programs, their murals and street drawings, and special events at the Festival.

Istanbul’s Street art festival is Turkey’s first annual street art and post-graffiti Festival. The Festival was founded by the artist and graphics designer Pertev Emre Tastaban in 2007.

Living Walls is an annual street art conference founded in 2009. 2010 it was hosted in Atlanta and 2011 jointly in Atlanta and Albany, New York. Living Walls also actively promoted street art at Art Basel Miami Beach in 2011.

The RVA Street Art Festival, a street art festival in Richmond, Virginia, began in 2012. Edward Trask and Jon Baliles organize it. 2012 the Festival took place along the Canal Walk; in 2013, it occurred at the vacant GRTC lot on Cary Street.

The Pasadena Chalk Festival, held annually in Pasadena, California, is the largest street-art Festival in the world, according to Guinness World Records. The 2010 edition involved about six hundred artists of all ages and skills and attracted more than 100,000 visitors.

UMA – Universal Museum of Art launched a comprehensive “A Walk into Street Art” exhibition in April 2018. This exhibition in virtual reality offers works from Banksy, JR, JefAérosol, Vhils, Shepard Fairey, and Keith Haring, among others.

The Eureka Street Art Festival is an annual public art event in Humboldt County, California—artists from California and worldwide paint murals and create street art during a week-long festival. The 2018 festival saw 24 artists create 22 public art pieces in the city’s Old Town area, focusing on Opera Alley. The 2019 festival is centred on the Downtown region.

India is the centre of Street art and Graffiti

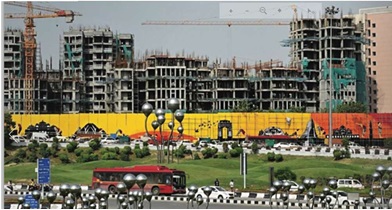

In February 2016, artwork on the walls of Delhi’s Lodhi Colony transformed it into India’s first public art district’. Conceived and coordinated by St+art India Foundation, an initiative organising street art festivals and similar events all over the country since its inception in 2014, the vibrant interventions were widely hailed. Artists from across the world convened for the two-month-long festival to create their pieces on the concave surfaces of the central Delhi neighbourhood, not far from the buildings of public administration that mark the city as India’s capital. Vibrant and layered as some of the art is, the fact that street art comprises a curated experience in the seat of national power suggests that it has a decidedly different history in this country than in other parts of the world.

This long-read-research article about Street Art- Graffiti in the Indian context brings multi-layer ideas about social life and street art as a context itself. Read the first part of this research article here: Street Art and Graffiti In Indian Public Spaces. Read the Second article: Historical Background of Graffiti and Street Art in India.

In New York, where Graffiti and, later, street art originated, the form was a backlash to urban blight and marginalisation of communities because of the government’s city planning schemes and a broader social context such as the Vietnam War and economic recession. Artist Henry Chalfant spells this out in his foreword to Cedar Lewisohn’s Street Art: The Graffiti Revolution: “Street art, the natural heir to Graffiti, is rooted in the creativity of the dislocated and alienated urban communities…in the second half of the twentieth century inherits its spirit from hip hop,

an autonomous subculture.”

In South Asian cities, public space has always been far less regulated and somewhat untended, being the site of local advertisements, political slogans and religious iconography. Due to a long history of murals stretching thousands of years, many street artists in India inherit a tradition of wall painting. What constitutes Graffiti in India might also be debatable – initials of young lovers on the walls of heritage monuments or promotional campaigns during election time are part of the commons. Though state governments have passed laws against defacing property, imagery and writing on the streets, have been long-standing traditions. Only in the past decade or so did’ street art’ emerge in metropolitan and Tier 1 cities. The expansive geography and political urgency initially made it a crucible for contemporary, self-conscious street art in Delhi and the NCR. Artists like Daku and Boss have been making their presence felt since the late 2000s, and more recently, several individuals, collectives and organisations engaging with the form have emerged in the area; a talk at Apeejay Arts, Delhi, in March 2015, titled, ‘Street Art in India: Then and Now’ signalled that street art had become a part of the mainstream discourse on visual culture. The Delhi government has cottoned on the NDMC, DMRC, and CPWD, which have lately been commissioning street artists to give some buildings a facelift.

Hanif Kureshi, a Mumbai-based artist who co-founded St+art Foundation in 2014, cleaves street art from its more anti-establishment ancestor, Graffiti, “Street art and graffiti constitute two different kinds of forms and ecologies.” He affirms the assertion about the anti-establishment ethos of the latter, “Graffiti is illegal and non-commercial, but street art is more positive. It’s about beautifying public spaces with all the permissions in place.” In 2011, Kureshi, a former graffiti artist who switched to street art, documented the “handpainted type” of sign painters across India. This is analogous to the stylised lettering that defined Graffiti in its original North American incarnation. For the past three years, St+art Foundation has been organising festivals in Delhi, Mumbai and Bengaluru and aims to make art accessible to a larger audience.

One of the first projects by Delhi Street Art (DSA), a collective started four years ago by Yogesh Saini, was at Lodhi Gardens – painting garbage cans to discourage people from littering. In 2014, DSA partnered with the NDMC to revivify the capital’s Shankar Market.

It often supports other programmes and artists seeking permissions within Delhi and is associated with over 400 artists worldwide. Apart from organising open events involving amateur and professional artist volunteers, St+art and DSA also execute work commissioned by government bodies, corporate clients and NGOs in metros and smaller cities. These entities make odd bedfellows and underscore the stark difference in ethos between Graffiti and street art.

There is an element of social entrepreneurship in the ecology circumscribing street art, and joint rhetoric of beauty and mass sensitisation recurs in conversations about it. Kureshi and Saini assert that a part of their aim is to make art accessible to a broader viewership. AnpuVarkey, known for her pictures of cats in South Delhi neighbourhoods, collaborated with German artist Hendrik Beikirch on a mural of Gandhi at the Delhi Police Headquarters. She says, “The deficiency of museums makes this medium important. What is to be observed is the public knowledge of such art forms, from the ricksha wallah to a policeman.” This promises some of the same political thrills but is neutralised by the market-oriented culture in which it is nurtured. When asked about the inclusive nature of DSA’s collaborative projects, Saini says, “For our commissioned pieces, the artists have first to prove themselves.” This is at odds with the Graffiti that South Delhi-based artists like Daku and Boss came to be known for a decade ago, more in line with the impulse to ‘tag’ and claim the city by artistically scrawling one’s name on public walls. Graffiti as a textual response to dominant socio-economic forces like big government and capitalistic urbanisation was initially about disenfranchised folk marking their territory. This attitude has not taken root in India, with any subversive spirit being tamed by the adoption of the less offensive genre of street art.

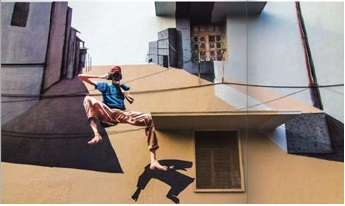

By themselves, creative acts like art-making can be profoundly political, allowing for a dialogue between those in power and those without it – using democratic means like public walls to make a point provides for all kinds of groups to do this. While St+art and DSA have worked on commissions by municipalities and public transport corporations, individual artists and independent collectives juggle between autonomous works and commissioned pieces. Many artists straddle the various options available in public art, the commercial and the socio-politically responsive. An example of such an artist, RuchinSoni, trained as a muralist and has to his credit the creeping figure on a flyover near ISBT. “That’s for me, but if you work to support yourself, you must take up commissions: these can be government or commercial.” He has worked on projects as diverse as painting the Dhaula Kuan Metro station food court and the OLX office in Gurgaon; he has also worked with a village community in Chhattisgarh as part of a UNDP initiative.

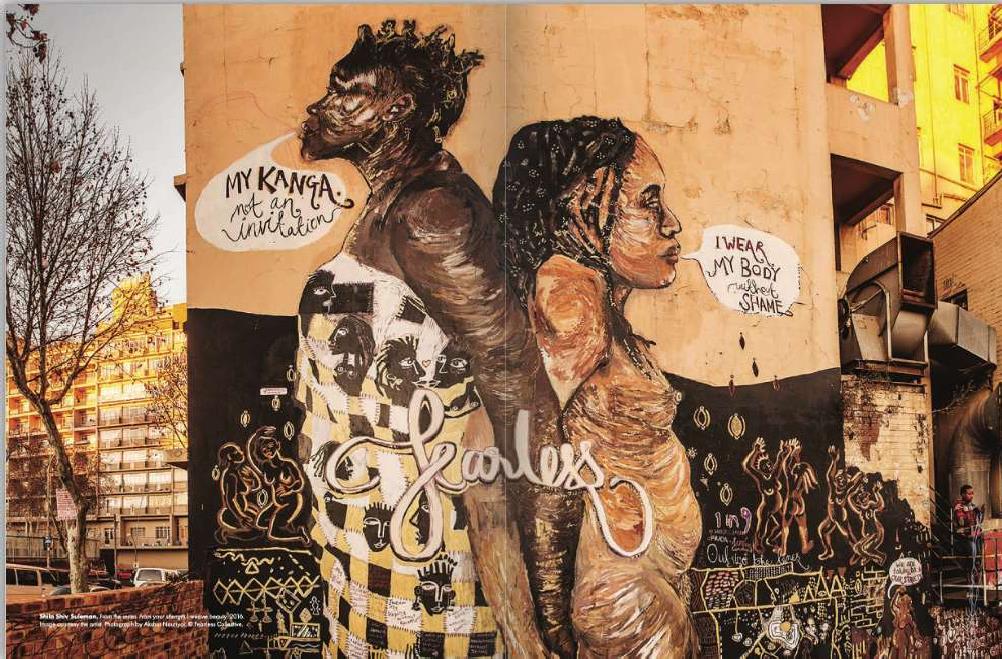

The non-profit sector offers street artists looking to remain faithful to the spirit of the form an opportunity to combine their craft with the confidence that generated it. Working with alienated communities to enable them to take charge of their environs through art reveals the political power of creative expression. Shilo Shiv Suleman describes her work with the Fearless Collective that she founded as moving towards “a common creative goal”. She took to street art after the Nirbhaya rape case in 2012. She conceived the form as something that evolves from community interactions through immersive and participatory processes like workshops. She represents a position that some artists have taken to resist the commodification of public life while practising legally. “We always take the consent of the people whose walls we make our art on. This can sometimes be state or local authorities, but we would never do a commissioned piece.” While Suleman’s Fearless Collective has worked with sex workers in Delhi, artist Harsh Raman encountered the possibilities of street art through the prism of gender injustice. He had previously spoken about how the company registrar did not accept his mother’s name when he registered his company, Harkat Studios. In response, he collaborated with an NGO and a German all-women graffiti crew to paint Delhi’s red light district, GB Road. Besides works by bands like the Aerosol Assassins Crew, his works and Varkey’s are also part of the Lodhi Art District.

Lodhi Art District has come about due to collaboration between St+art, the Central Public Works Division and the Delhi Urban Art Commission. The DUAC was set up by an Act of Parliament in 1973 to “advise the Government of India in the matter of preserving, developing and maintaining the aesthetic quality of urban and environmental design within Delhi”. Exponents of the street-art-as-enterprise model, such as DSA’s Yogesh Saini, feel that government patronage “doesn’t mean that there’s no freedom, it just means more responsibility”. The institutionalization of a potentially mischievous artistic praxis is also represented by how Daku’s career has progressed over the past ten years. One of his works, titled Time Changes Everything, a stunning piece involving the play of light and shadow on mirror letter cut-outs, is also at the Lodhi Art District, part of a legitimate space. During a time when the Central government’s Swachh Bharat Abhiyan is at its most vigorous, the alignment of artists with the state gives one pause. The usual problems of male domination and elite over-representation mar the landscape of street art, divulging that the streets don’t belong to everyone in the same way.

An essential facet of the street art movement in Delhi and elsewhere in India is the materiality of the form – the technologies and labour it is constituted by. Kureshi points out how, before the late 2000s, the sort of aerosol paint needed to render art on walls was available to a few privileged artists. This might be why emerging in India took such a long time. Some works are elaborate enough to qualify as gallery-grade installation pieces: Daku’s Time Changes Everything made extensive use of Google SketchUp, a 3D modelling program to help understand shadowplay, while Beikirch and Varkey’s Gandhi had the painters going up and down in an aerial lift. In addition, the physical act of making art in full view of the street and with media not meant for easy eye and hand coordination is daunting. Varkey draws on their training as painters to do this, using perceptual tricks Soni, Suleman and lots of practice to Transfer the image from their minds to a draft and then onto a wall. Then there are the problems with the Public Display of Artistry in India. For Varkey, the essential skill is endurance “to heat, cold (difficult working conditions), shaky ladders and scaffoldings, and contending that sometimes there is no place to relieve yourself.” This is only sometimes unrewarding. “This the dizzy feeling of scaling heights and not knowing the outcome becomes the biggest allure,” she adds.

As the somewhat predictable Kolkata Street Art Festival, guided by Jogen Chowdhury, recently demonstrated, the aesthetics of what was once a vibrant tradition of public art has turned mawkish, glorifying self-absorption. The initiative began in July this year and intends to paint five hundred walls across twenty locations over the next five years. BarunSaha’s kitschy, tulip-holding mermaids and geese-gazing lovers left this writer yearning for the days of the once ubiquitous political graffiti, which was full of clever images and delightful puns.

What has happened to street art in Kolkata? Politically and socially aw re murals, some of the city’s most iconic images, have all but disappeared. They were chanced upon like old friends all over town: mostly chipped and invariably shabby, their down-at-heel state a metaphor for the city. The be t street art reflects broader trends in society – and with some notable exceptions, which will be discussed below – these are self-indulgent expressions devoid of beauty, humour and irony. A stretch of wall painted with the colourful image of a mermaid with a tulip is more attractive than an empty or besmirched wall. This is undoubtedly true, but what does it mean in the broader scheme of the city’s p street art is an inalienable part?

From the 1960s to the 1990s, street art in Calcutta was highly politicised, and unlike today, it was fundamentally different in content from that which was officially approved. It was a multi-layered and textured conversation between the frequently anonymous artist, the public and the

constructed environment. Raging from drawings of Naxalite party workers killed by the police sketched using pieces of charcoal taken from their funeral pyres to portraits of Indira Gandhi in psyche colours, these images were provocative, irreverent, and socially aware. They gave vent to a deeply felt sense of resentment and anger against the establishment. These images were sharply divided along ideological lines, creating a shared visual public space where ideas could be expressed metaphorically and directly. The civic authorities essentially disregarded the creation of these works, especially during elections when every available wall space was used to score a political point. The remaining surviving images chronicle some of the most tumultuous decades in the state’s history and glimpse a fast-disappearing form of visual modernity. From monochromatic muscular workers wielding communist flags near Jadavpur University, looking as though they’ve emerged from a Chittaprosad graphic to caricatures with bilingual puns in central Kolkata, these works by unknown artists captured the spirit of a city engaged and grappling with the issues of the day.

This long-read-research article about Street Art- Graffiti in the Indian context brings multi-layer ideas about social life and street art as a context itself. Read the first part of this research article here: Street Art and Graffiti In Indian Public Spaces. Read the Second article: Historical Background of Graffiti and Street Art in India.

Many of these full images have been replaced by uninspiring homilies. A noteworthy and significant project, however, is missing, conceptualised by Leena Kejriwal, which highlights the unspeakable menace of human trafficking and juvenile prostitution. Launched in New Delhi in 2014 and involving artists, students, and girls rescued from traffickers, these images are now to be found all over Kolkata. Depicting a dark silhouette of a female form, often with a number, this community-based initiative focuses on awareness and, through that, change. It moves the discussion of the fraught social issue to the creative sphere and, in doing so, brings what is still considered a touchy, if not a taboo subject, out of the shadows. The sameness of the image underscores the point that an individual is not a faceless statistic, and to view her as such is not merely unacceptable but grotesque. The strength of these images lies in their essential enigma. It is, however, not inaccessible or obscure and takes a grim subject and emphasises it, pushing the audience to think about the issue. It is a strangely moving sight to find young girls on their way to or from school stopping next to these ubiquitous images to ponder what may have been. This is an instance of a project that has used street art’s inherent power to draw attention to a pressing topic.

Then there are collectives like SHREK, SNIK and SHOCK, which reveal their anonymity and bring an entirely new, cosmopolitan aesthetic to the city’s walls. Preferring to be known by pseudonyms and drawing mainly on popular cultural references, they reach out to their audience across social media. They have turned surfaces of some of the city’s otherwise dreary eastern and southern suburbs into surreal gems. Surprisingly polite (they always seek consent before getting to work), they see themselves as guerrillas out to reclaim the public sphere and voice their creative concerns. From Ganesha and Buddha languidly reclining on bolsters to a winking man with a levitating skull, these are works of considerable skill which make intelligent use of language and script and convey radical ideas about the nature of art and aesthetics. They are not seen as particularly controversial – especially since most of these artists avoid the overtly political – but produce complex and beautiful expressions that voice cultural concerns both at the individual and the collective level. For many, though, these images are mainly inaccessible and difficult to read and are seen as a somewhat elitist expression devoid of more profound symbolism.

There are several other instances of stand-out works. Still, the distinction must be borne in mind that the city’s officially approved and commissioned street art, as seen at the festival, needs to be more attractive. In contrast, individuals and collectives working independently are far more successful in form and content. In an urban environment that is crying out for and lends itself to street art, it is surprising that there have not been such exuberant voices to depict social change, protest and dialogue. A rich tradition of student activism has not made much impact in the visual sphere, with the walls of the city’s many colleges and universities displaying nothing more than banal political rhetoric.

Street art – including sculpture – can generate an intellectual discussion, and Kolkata is uniquely placed to use this. Unfortunately, there is minimal reflection on the city’s past and present and few efforts to engage with history. For instance, there is virtually no art in the recently opened underground stations, although the Kolkata Street Art Festival is meant to remedy that. The older stations – including Esplanade in the heart of the city where an Anjolie Ela Menon mural was covered up for years and is now damaged irreparably – use stereotypical images and reproductions where original works by local as well as other artists would have been welcome. Thus, very little street art reflects the idiosyncrasies of this quirky city. The articulation and amplification of a variety of artistic messages are muted. Given the amount of construction which is perennially on or the number of crumbling towers, it is surprising that street art is less widespread. One reason is possibly that political parties and their affiliates tend to guard their patches fiercely, and often an innocent visual can be misconstrued with dire results for the artist. Schools make the occasional valiant attempt at encouraging their students. Sadly, the results are pleasing with some of the excellent walls, but not more than that. Where is the city’s inherent rebelliousness and spirit of adventure regarding street art? Street art goes hand-in-hand with underground culture, and it is a sad commentary on a city which has, over the years, produced some of the most provocative, anti-authoritarian creative minds that many of its walls are manifestations of ugliness and kitsch without a trace of irony.

Much street art goes unnoticed and much taken for granted, like the indefatigable KC Paul’s chalk diagrams of a geocentric universe which are to be found on several street corners. Remarkably more for their aesthetics than their scientific logic, these are thought-provoking, stimulating, often surreal works Kolkata mer its. Content and context must come together again to delight, infuriate and even perplex audiences. More collaborative projects like Missing, which engage with communities, must be worked on. Like any great metropolis, Kolkata is a palimpsest, bursting with stories and hopes, and aspirations to be articulated. The city’s artists must pick up their aerosols and brushes to bring this to fruition so that a great artistic and intellectual tradition is different from much else in the city, submerged by the trite and the aesthetically unappealing.

Photograph by Kanishka Mukherjee. © Missing Link Trust

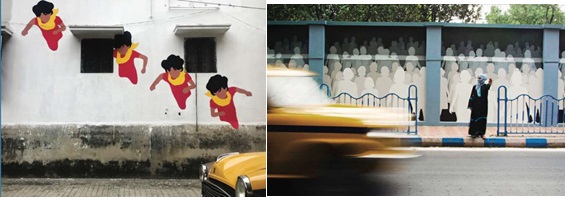

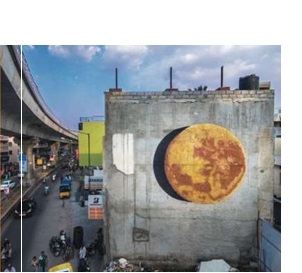

Between old neighbourhoods and chaotic development projects in Bengaluru, an assortment of graffiti, street and public art projects give the city a makeover.

An inscription or a mark on a wall can have an everlasting impact – be it the irreverent scrawl in a classroom or the clichéd lovers’ hearts carved at tourist s spraypaint jobs along pedestrian walkways.

The idea of graffiti in urban metropolises does, admittedly, often come close to that of defacement and vandalism – as attested by reports (albeit unverified in most instances) of artists like Banksy being detained by authorities on their clandestine night runs.

In Bengaluru, however, graffiti makes its presence felt in a ‘positive’ manner and even tends to play a beneficial role – beautifying and sprucing up the otherwise eyesore stretches of the city’s landscape. Most of the credit goes to local cultural groups and art collectives conducting independent and, at times, collaborative projects.

The language of art appreciation takes a back seat, quite literally, on a cab ride from the airport into Bengaluru city. At the end of the main tolled speedway, the road on either side is lined with graffiti and street art – most pleasantly colourful. But this scrawl doesn’t belong to the underground graffiti style in vogue in the West and is now increasingly visible in parts of South East Asia. Instead, these works are commissioned by local authorities and are predominantly simplistic depictions of flora and fauna, landscapes and state or national monuments.

This long-read-research article about Street Art- Graffiti in the Indian context brings multi-layer ideas about social life and street art as a context itself. Read the first part of this research article here: Street Art and Graffiti In Indian Public Spaces. Read the Second article: Historical Background of Graffiti and Street Art in India.

Admittedly, this introduction to Bengaluru’s street art could be more encouraging. A commissioned sculpture is a baffling example of poorly administered public art at the traffic roundabout outside the city’s Cantonment Railway Station. Inspired by a zoological concept, the statue has a life-size elephant with a big cat, a rhinoceros, a turtle, and a vulture all perched on top of it. An initiative of the BBMP municipal board, the sculpture has come in for much ridicule and is known to cause traffic snarls by its mere presence.

Thankfully, there’s more to explore as far as Bengaluru’s street art is concerned- even if, for the most part, it serves the explicit purpose of drawing people’s attention away from unsightly, uncared-for nooks and corners of old neighbourhoods, and especially, from heaps of uncleared garbage. Some of the works plastering the walls come with emphatic messages – such as those of Shilo Shiv Suleman, part of the Fearless Collective, which brings together over 400 artists in the country and works with a core group of volunteers including Shalaka Pai, Aarthi Parthasarathy, Kasha Frese and Aruna Chandra Sekhar, to provide a voice for women’s rights against gender violence.

Typically exploring the caricatural register, with characters sporting the artist’s signature wide-open eyes, these murals include empowering messages underscoring women’s need for safe spaces and urging them to reclaim the streets. Suleman’s frescoes fit well as public art landmarks – inspiring students of the all-girl Jyoti Nivas College in Koramangala and visitors at the bustling flower market in the KR Market area, where the group frequently conducts community-based projects.

The Aravani Art Project, founded by Poornima Sukumar with other like-minded confreres, is another initiative that uses street art to galvanise support for a cause by getting transgender people to engage in significant cultural interventions. The group works with artists, photographers, filmmakers and others to paint murals and create conversations about pertinent social issues, as in work titled NaavuIdhevi (‘We Exist’ in Kannada) on a stretch along the Dhanvantri Road underpass. While many street and public art initiatives are conventional, projects such as these lend relevance and potency to equality-focused activism. They also channel marginalised voices successfully.

In recent times, the city’s most considerable makeover efforts have been conducted by the St+art India Foundation, led by Akshat Nauriyal, Arjun Bahl, Giulia Ambrogi, Hanif Kureshi and Thanish Thomas, along with several international guest artists. The group is known for working in the capital and Mumbai, based on the simple premise of Art for Everyone. As part of the Art in Transit festival in October last year, the group was joined by students from the Srishti School of Art, Design and Technology as they went about creating massive art interventions at locations across the city through various tours, workshops and collaborative projects. The Start India Foundation’s efforts are prominently visible at the Bangalore Metro Rail Corporation stations. Several Indian and guest artists have created visual narratives at Cubbon Park, the Metro stations on MG Road, and the Majestic. Among the many works made during the festival, Sameer Kulavoor from Mumbai also gave the Kempegowda Metro Station, ostensibly the largest in Asia, a vibrant makeover, representing the chaos and confusion of the central transit area.

The Goethe Institute has notably been supporting many of these initiatives, beginning with the Urban Avant-Garde project of 2012, which resulted in the transformation of the old-Bengaluru neighbourhood of Malleswaram, along with the MalleswaramAccesseibility Project.

Amitabh Kumar and Arzu Mistry, along with some Srishti Institute of Art, Design and Technology students, have come up with a striking mural of a series of nurturing hands, on the exterior walls of the institute, on the main CMH Road avenue. The site is easy to notice, and passersby commonly gather around it for discussions over cups of filter coffee. Kumar has also led an initiative to metamorphose the service road alongside the busy Yeshwathpur Metro station, getting art students to paint on the stalls of the area’s street vendors. The students of Srishti have also converted many portions of the Yelahanka area, bringing artistic relief to the humdrum residential surroundings.

The collective Jagga, in turn, has also worked with the BBMP to transform the cement pillars holding the flyover under the KH Double Road flyover. Brightly coloured, with cheerful sunshiny themes, these works go a long way in breaking the monotony of being stranded in traffic.

While all this augurs well for mainstream street and public art in Bengaluru, a few stray samples of real subversive graffiti are also present in the city. The artists who go by the pseudonyms Guess Who? (very popular in Kochi), Daku, Marko 93, Stinkfish and Sadhu X, apart from art groups such as the Klatsch Collective, have created many amusing and quirky works strewn across parts of the city, many of them on Church Street, with few scattered as far as Kalyan Nagar, ShunnalLigade aka The Bathroom Painter, UllasHydoor and Arjun Srinivas has also left their artistic imprints on the cityscape – noticeably, on one side of the Hard Rock Café pub. One can still find instances from Leena Kejriwal’s Missing project from a few years back, featuring silhouettes of young girls accompanied by the hashtag’ #missing’ and a helpline number to create awareness about child trafficking.

BaadalNanjundaswamy has caused a bit of splash in the media with his ‘pothole protests’ by creating three-dimensional paintings around manholes, open drains and stretches of tarmac in a state of disrepair in the localities of RT Nagar to alert the authorities about repair and maintenance. The effort did pay off, as the potholes were eventually patched up and the streets fixed, admittedly undoing Nanjundaswamy’s artistic interventions. However, the artist’s other works encouraging no-litter zones remain along some of the area’s paved stretches.

Intelligent graffiti has an unexpected quality- of sneakily offering a thought and an alternative point of view to create a lasting impression on the minds of citizens. There are only a handful of standout examples. Consider the stencilled line ‘# againstallodds’ next to the imprinted figure of a running woman with the tag Lalitta Babar, the champion long-distance runner, at a few street corners. The works certainly do the job of informing people who might not be in the know while also ensuring a message that rings loud and true.

Photograph by Pranav Gohil. Images courtesy: St+art India Foundation.

Note

- Smith, Howard (21 December 1982). “Apple of Temptation”. The Village Voice. Manhattan, New York, US. p. 38.

- Zotti, Ed (4 August 2000). “What’s the origin of ‘Kilroy was here’?”. Straight Dope; staff report from the Science Advisory Board. Sun-Times Media, LLC. Retrieved 29 October 2016

- Robinson, David (1990) Soho Walls – Beyond Graffiti, Thames & Hudson, NY, ISBN 978-0-500-27602-0

- Drasher, Katherine (30 June 1983). “Avant’s on the Street”. The Villager. pp. 31–32. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

- Zox-Weaver, Annalisa (1 June 2015). “Institutional Guerilla Art Open Access: The Public Sculpture of FlorentijnHofman”. Sculpture Review. 3 (22–26).

- Smith, Howard (21 December 1982). “Apple of Temptation”. The Village Voice. Manhattan, New York, US. p. 38.

- Tierney, John (6 November 1990). “A Wall in SoHo; Enter 2 Artists, Feuding”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. OCLC 1645522. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- Strausbaugh, John (5–11 April 1995). “Renaissance Man”. New York Press. Vol. 8, no. 14. p. Cover, 15, 16. ISSN 0362-4331. OCLC 1645522

- “Moncada v. Rubin-Spangle Gallery, Inc. – November 4, 1993”. Leagle.com. 4 November 1993. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- Landes, William M.; Posner, Richard A. (2003). The Economic Structure of Intellectual Property Law (illustrated ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts, US: Harvard University Press. p. 285. ISBN 978-0-674-01204-2. OCLC 52208762. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- Lerner, Ralph E.; Bresler, Judith (2005). Art law: the guide for collectors, investors, dealers, and artists (3rd ed.). New York City, New York, US: Practising Law Institute. ISBN978-1-4024-0650-8. OCLC 62207673. Retrieved 4 May 2012

- Kostelanetz, Richard (2003). SoHo; The Rise and Fall of an Artist’s Colony (1st ed.). New York, NY: Routledge. pp. 102–104. ISBN 978-0 415-96572-9. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- Landes, William M.; Posner, Richard A. (2003). The Economic Structure of Intellectual Property Law (illustrated ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts, US: Harvard University Press. p. 285. ISBN 978-0-674-01204-2. OCLC 52208762. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- I AM THE BEST ARTIST Rene mural (1987). The Secret of My Success (Comedy film). US: Universal Studios. “Incredible street art tours”. Retrieved 26 February 2015

- Means, Gary. “Alternative London Street Art Guides”. alternativeldn.com. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- “Alternative Berlin”. alternativeberlin.com. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- Bross, F. (2017): Beer Prices Correlate with the Quality of Illegal Urban Art. A Case Study on the Relationship Between Street Art and Gentrification in a Berlin Neighborhood. Mimeo.

- Salib, Peter (Fall 2015). “The Law of Banksy: Who Owns Street Art?”. University of Chicago Law Review. 82 (4): 293. SSRN 2711789. 17 U.S.C. § 102

- “moral, adj.”. OED Online. September 2011. Oxford University Press. 25 October 2011.

- H&M Lawsuit Against Street Artist Could Change Copyright Law. (2018). Hyperallergic. Retrieved 28 April 2019, from https://hyperallergic.com/432709/hm-lawsuit-street-artist-revok-copyright-law/

- Graffiti Cannot be Copyright Protected, Claims Moschino, Jeremy Scott. (2016). The Fashion Law. Retrieved 29 April 2019. from http://www.thefashionlaw.com/home/graffiti-cannot-be-copyright-protected-claims-moschino-jeremy-scott Archived 1 March 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- Unchartered Territory: Enforcing an Artist’s Rights in Street Art | HHR Art Law. (2017). HHR Art Law. Retrieved 29 April 2019, from https://www.hhrartlaw.com/2017/01/unchartered-territory-enforcing-an-artists-rights-in-street-art/

- Unchartered Territory: Enforcing an Artist’s Rights in Street Art | HHR Art Law. (2017). HHR Art Law. Retrieved 29 April 2019, from https://www.hhrartlaw.com/2017/01/unchartered-territory-enforcing-an-artists-rights-in-street-art/

- Finn, R. (2014). 5Pointz Arts Center, and Its Graffiti, Is on Borrowed Time. Nytimes.com. Retrieved 29 April 2019, from https://www.nytimes.com/2011/08/28/nyregion/5pointz-arts-center-and-its-graffiti-is-on-borrowed-time.html https://thelawreviews.co.uk/title/the-art-law- review/india#:~:text=The%20rights%20of%20consumers%20in,services%20of%20providing%20proper%20services.

- Bloch, Stefano. 2015. “Street Art, Public City: Law, Crime and the Urban Imagination.” Urban Studies (Sage Publications, Ltd.) 52(13):2500-2503.

- Campos, Ricardo. 2015. “Youth, Graffiti, and the Aestheticization of Transgression.” Social Analysis 59(3):17-40.

- Bacharach, Sondra (4 January 2016). “Street Art and Consent”. British Journal of Aesthetics. 55 (4): 481–495. doi:10.1093/aesthj/ayv030.

- Sisko (Summer 2015). “Guerilla Sculpture: Free Speech and Dissent”. Sculpture Review. 64 (2): 26–35.

- The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 68:3, Summer 2010

- The Contested Gallery: Street Art, Ethnography and the Search for Urban Understandings, AmeriQuest Vol. 2 nr. 1, 2005

- Bacharach, Sondra (4 January 2016). “Street Art and Consent”. British Journal of Aesthetics. 55 (4): 481–495. doi:10.1093/aesthj/ayv030.

- Bacharach, Sondra (4 January 2016). “Street Art and Consent”. British Journal of Aesthetics. 55 (4): 481–495. doi:10.1093/aesthj/ayv030.

- ITV News (10 December 2021). “Banksy and other street art goes on display at Peterborough Museum”. ITV. Retrieved 10 January 2022. 98C. Gogarty and D. Clensy (28 March 2019). “A look back at when Banksy took over Bristol Museum in 2009”. Bristol Post. Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- Guetzkow 2002, Joshua. “The World is Our Canvas: Nonprofit Empowers Street Artists to Uplift Neighborhoods” (PDF).

- Crouch, Angie. “How the Arts Impact Communities”. NBC. NBC Los Angeles.

- “Asia’s tallest mural – By Hendrik Beikirch”. 5 September 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- Winks, Mathias (14 December 2016). “Curiosity” – New Mural by Street Artist Seth Globepainter in Dubai // UAE”. MC WinkelsweBlog (in German). Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- McFarlane, Nyree (29 November 2016). “Satwa is currently turning into a huge street art gallery”. What’s On. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- Lewisohn, Cedar (2008) Street Art: The Graffiti Revolution, Tate Gallery, London, England, ISBN 978-1-85437-767-8.

- Chalk Festival, a forty-page guide to the 2012 Sarasota Chalk Festival, Sarasota Observer, 28 October through 6 November 2012

- Go Turkey Tourism”.

- http://northeasternuniversityjournalism2011.wordpress.com/2011/07/18/in-istanbul-artists-take-their-ideas-to-the-streets/ Hannah Martin: In Istanbul, artists take their ideas to the streets, 18 July 2011, Retrieved 5 October 2011

- Guzner, Sonia (22 August 2011). “‘Living Walls’ Speaks Out Through Street Art”. The Emory Wheel. Archived from the original on 29 July

- Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- “Living Walls”. Archived from the original on 10 July 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- “2013 RVA Street Art Festival to revitalize GRTC property”. CBS6. 20 March 2013. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- Day, Brian (20 June 2015). World’s largest chalk art festival draws a crowd in Pasadena. Pasadena Star-News. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- “Living Walls”. Archived from the original on 10 July 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- “UMA – Universal Museum of Art”. Archived from the original on 6 May 2013. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- “A Walk Into Street Art”. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- Catsos, Jennifer. “Past Festivals”. Eureka Street Art Festival.