Introduction

The Iranian Revolution of 1979, also known as the Islamic Revolution or Enqelāb-e Eslāmī in Persian, was a significant event in Iran’s political landscape, disorienting Reza Shah Pahlavi’s seemingly stable governance. The revolution was fuelled by large-scale protests and widespread mobilisation. Shah’s concession and repression schemes led to the dictatorship’s downfall on February 11, 1979, establishing the foundation of an Islamic republic.

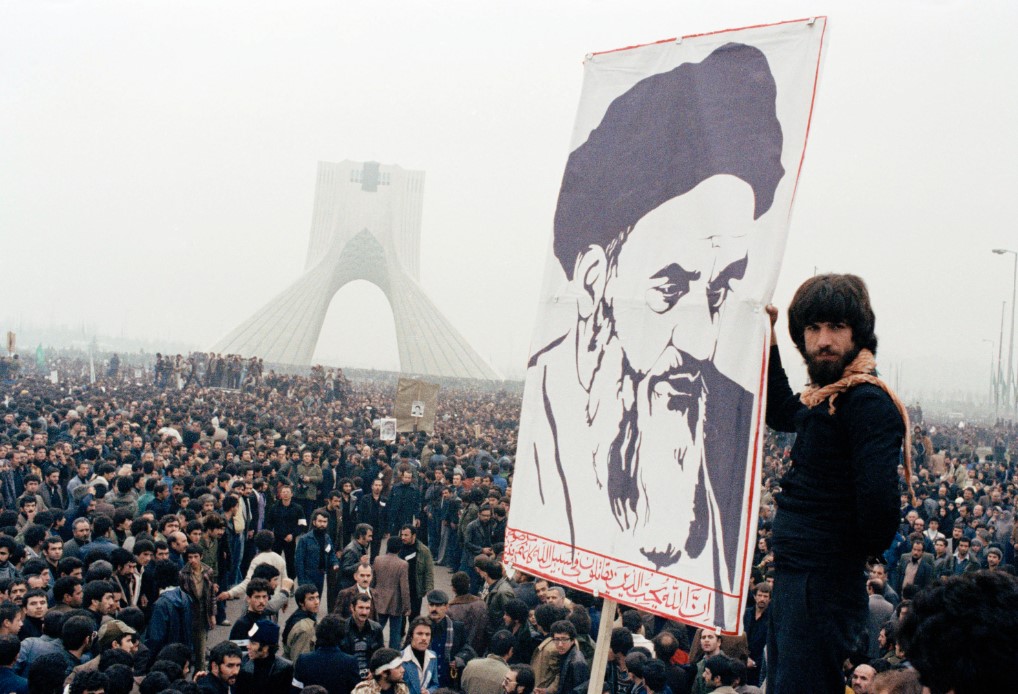

The 1979 Iranian Revolution protests, https://owlcation.com/

The 1979 Iranian Revolution protests, https://owlcation.com/

The Inception of Revolution

Iran’s 1979 revolution originated from the country’s extensive past. Social conflicts and foreign involvement from Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States suffocated the revolution for a long. The United Kingdom assisted Reza Shah Pahlavi in establishing a monarchy in 1921, but he was forced into exile in 1941, and his son Mohammad Reza Pahlavi inherited the throne. During the power struggle between Mohammed Reza Shah and Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh in 1953, the USA’s Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the UK’s Secret Intelligence Service staged an uprising against Mosaddegh’s government. After acquiring administrative power, Mohammad Reza Shah dissolved the parliament and initiated the White Revolution, an ambitious modernization programme that disrupted rural economies, and led to rapid urbanisation and Westernisation. The programme was economically successful but not distributed fairly, with significant repercussions on social norms and institutions. This episode raised concerns about democratic human rights.

Global financial turmoil along with shifts in Western oil consumption jeopardised the country’s economy in the 1970s, resulting in high rates of inflation and stagnation of Iranians’ buying power adversely affecting their standard of living. The Shah’s dictatorship expanded social repression. The opposition groups like the National Front and the pro-Soviet Tudeh Party were suppressed or outlawed. Censorship, monitoring, and harassment were frequently employed in response to social and political protests, and unlawful arrest and torture were prevalent.

In this Oct. 9, 1978 file photo, Iranian protesters demonstrate against Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi in Tehran, Iran. https://www.peoplesworld.org/

In this Oct. 9, 1978 file photo, Iranian protesters demonstrate against Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi in Tehran, Iran. https://www.peoplesworld.org/

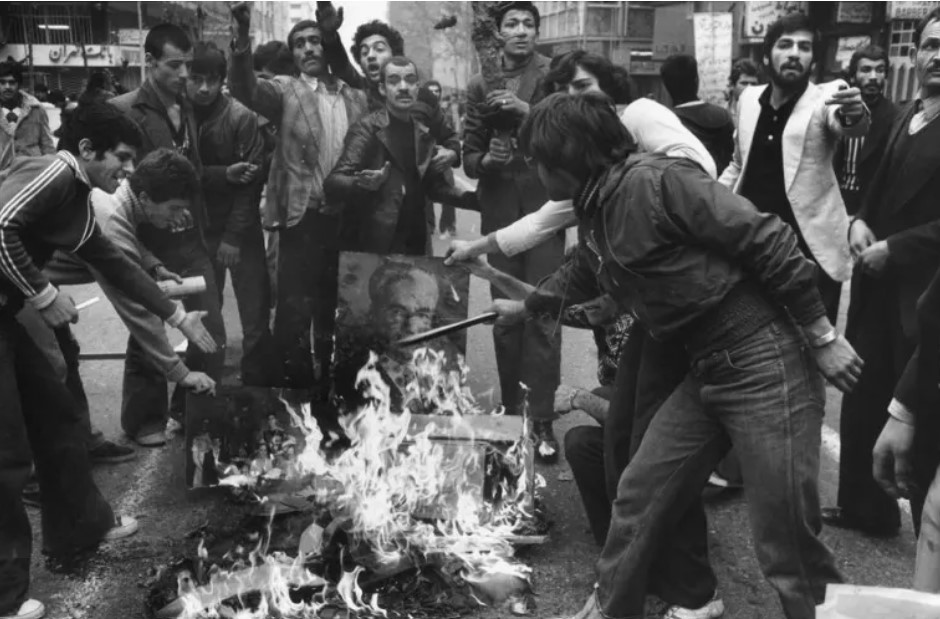

For the first time in almost a half-century, secular intellectuals, captivated by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s popular appeal, abandoned their goal of lowering the authority and influence of the Shi-i-ulama and advocated that the shah might be eliminated with the support of the ulama. Members of the National Front, the Tudeh Party, and its many subsidiary groups joined the ulama in their widespread resistance to the dictatorship of the Shah. The Shah’s dependence on the US, his close association with Israel, his involvement in prolonged wars with the largely Muslim Arab states and his ill-advised economic policies by his regime all contributed to the growing frequency of dissident opinion among the masses. Externally, Iran appeared to have a swiftly developing economy and modernising infrastructure, but in barely a generation, it had transformed itself from a traditional, conservative, and rural culture to an industrial, modern, and urban civilization. The Protests against the administration in 1978 highlighted the government’s inability to comply with promises made. As a result, a huge uprising struck Mohammad Reza Shah’s regime in 1979.

“To comprehend the magnitude of the Iranian revolution, we first need to understand the origins of the revolution: what were the factors that drove the country to such fervent protest?”

The primary objective of the Iranian Revolution was to dethrone Mohamed Reza Shah Pahlavi, the country’s monarch since 1941. Even though Iran experienced periods of sustained financial prosperity during Shah’s leadership, the state was essentially a dictatorship on the internal front. Furthermore, many fundamentalists opposed the ruler’s ambitious industrialization agenda in the 1960s, which redistributed land and pushed for social transformations. Many people believed that Shah’s actions damaged Shia traditions in Iran and served primarily foreign interests. Iran’s economic collapse in 1977, which resulted in severe unemployment and growing inflation, became a catalyst for the revolt of 1979, discussed in detail further.

Women played a prominent part in Iran’s 1979 revolution, https://theconversation.com/

Women played a prominent part in Iran’s 1979 revolution, https://theconversation.com/

The Historic Revolt of 1979

In reaction to malicious statements in a Tehran newspaper, hundreds of young Iranian students and unemployed immigrants rallied against the Shah of Iran in 1978. The shah, who suffered from illness, vacillated between concession and repression, believing that the protests were part of an international conspiracy. Many individuals were killed by government troops, exacerbating the bloodshed in a Shia culture where martyrdom is central to religious expression. The violence and disruption continued to worsen, culminating in the imposition of martial law on September 8. The protests led both government workers and oil workers to go on strike, effectively shutting down the oil business. On December 10, hundreds of thousands of protesters marched through the city of Tehran.

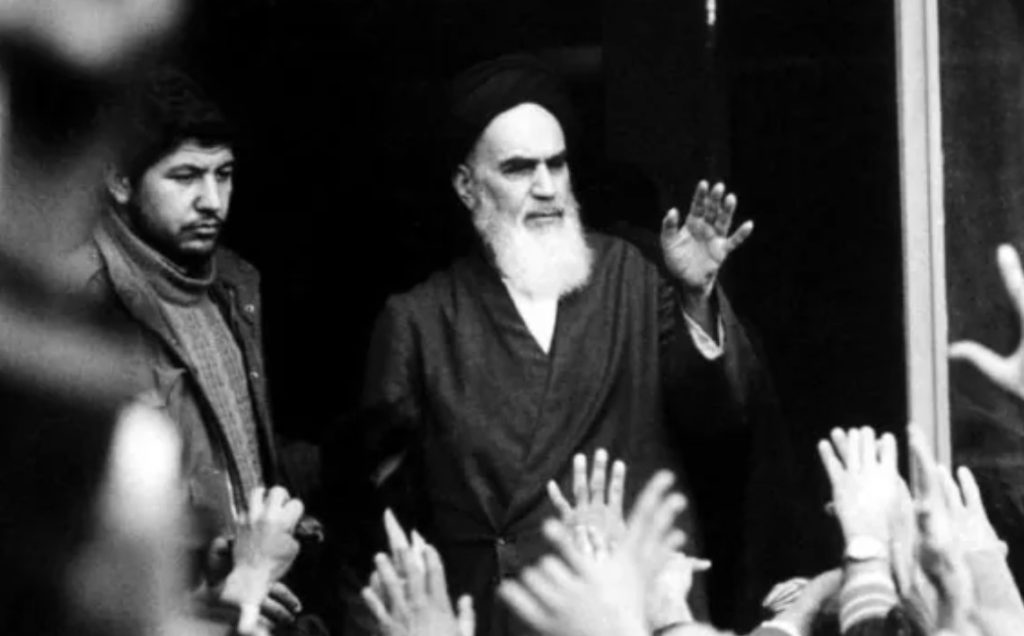

During his exile, Khomeini orchestrated a rise of opposition seeking the Shah’s resignation. The Shah and his family fled Iran in January 1979, and the Regency Council stopped functioning. Shahpur Bakhtiar, chosen by the Shah before his departure, was unable to reach an agreement with either his former National Front colleagues or Khomeini. Over a million people rallied in Tehran, demonstrating Khomeini’s widespread support. Iran’s military forces declared neutrality on February 11, thus deposing the shah’s authority. Bakhtiar escaped to France and finally went into exile.

Khomeini emerged as the dominating political figure in post-revolution Iran, https://www.aljazeera.com/

Khomeini emerged as the dominating political figure in post-revolution Iran, https://www.aljazeera.com/

The Aftermath of the Revolution

Following a nationwide vote in elections, Iran declared itself an Islamic republic on April 1, 1979. Khomeini led the religious community in resisting the expulsion of their earlier left-wing, nationalist, and intellectual acquaintances from power and enforced conservative social norms. The Family Protection Act, which safeguarded women’s rights, was proclaimed ineffective and unlawful. The revolutionary mosque-based bands known as komitehs, patrolled the streets, enforcing Islamic dress codes and behavioural regulations. Khomeini’s Revolutionary Guards, an informal religious army intended to prevent CIA-backed conspiracies, carried out similar intimidation and repression of political parties. The militias and religious leaders who backed them sought to crush Western cultural influence, which resulted in the oppression and violence against the Western-educated elite. This anti-Western feeling was evident in the incident siege of the US embassy by Iranian protesters seeking the Shah’s extradition, in November 1979. This permitted Khomeini’s followers to claim to be as “anti-imperialist” as the political left, despite the regime’s suppression of most of its left-wing and moderate opponents.

In November 1979, the Assembly of Experts (Majles-e Khobregn), dominated by clerics, established a new constitution, forming a religious government based on Khomeini’s idea of velayat-e faqih which granted the Rahbar, or leader, vast authority. Conservatives who questioned the revolutionary fervour of moderates such as temporary Prime Minister Mehdi Bazargan and the republic’s first president, Abolhasan Bani-Sadr, were forced out of power.

“Iran hostage crisis”, Blindfolded American hostage surrounded by captors outside the U.S. embassy in Tehrān, November 9, 1979, https://www.britannica.com/

“Iran hostage crisis”, Blindfolded American hostage surrounded by captors outside the U.S. embassy in Tehrān, November 9, 1979, https://www.britannica.com/

In the aftermath of the Iranian revolution, a dual perspective evolved as a result of the assertion of leadership to impose strict religious rules. There were differing opinions on the revolution’s impact; for some, it was the most momentous and promising event in contemporary Islamic history; for others, it generated quite the opposite scenario than it had promised. The events of 1979 are still being debated, and various viewpoints are expressed by Iranians.

So, the question arises, “How did the Iranian Revolution derail so badly?”

The Eco-Political Impact of the Iranian Revolution

The overthrow of Iran’s Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi left Washington with a long-lasting geopolitical wound since it resulted in the establishment of a hostile organisation that held US nationals, hostage, carried out fatal attacks on US forces, and defined itself as an anti-imperial “resister” to hegemonic America. Meanwhile, the establishment of a theocratic tyranny in Iran came as a political surprise, reviving religious forces long suppressed by secular, Pan-Arab authoritarians. The Iranian revolution was essential in the emergence and spread of jihadist movements in the Arab World, boosting awareness of religion’s significance in political transformation. Tehran is blamed by critics for inflaming extremism in the Middle East and fostering rebellions. Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS) claimed that ‘the 1979 Iranian revolution reinforced religious rigidity and extremism in his nation’, whereas opponents argued that the monarchy serves a role in developing certain strains of political Islam and is intolerant of criticism. Thus, for many reasons, the movement that began with enormous optimism for the country’s freedom and future became a failed revolution.

The sign reads: “Long live anti-Imperialism and Democratic forces,” https://www.marxist.com/

The sign reads: “Long live anti-Imperialism and Democratic forces,” https://www.marxist.com/

Mohammad Omidvar, a member of the political bureau in Iran, argues that ‘the Iranian Revolution effectively deposed the Shah’s tyrannical rule and entered its social phase, replacing the socioeconomic system with a new one. The revolution’s slogans and programs, including nationalizing banks and international corporations, were implemented in the first year, but US and reactionary interference, including the Iraq-Iran War, interrupted the revolution and led to a theocratic nation.’

“No, I don’t think the revolution is over. The formation of a theocracy was both novel and anachronistic, and its ramifications will take time to play out,” said Boroujerdi, adding, “The revolution raised the political sophistication of the citizenry and gave birth to new institutions that are still in their infancy. As a result of the revolution, Iranian politics has become ‘real,’ and its permanence has become the new ‘normal,’ to which we must adjust.”

The rise of political Islam during the transformed nation of the Islamic Republic of Iran under Khomeini’s rule was not a predetermined phenomenon but an opportunity for Islamic forces to organize and mobilize the population. The revolution significantly impacted populations in Islamic countries and changed the image of Islam in the non-Muslim world, generating interest in political Islam among young Muslim Arabs and Turks, and putting concerns in the minds of all Muslim sovereigns around the world.

The Contradictions of Ideologies in the Islamic Republic of Iran

The main goal for Ayatollah Khomeini was not to establish freedom and nonviolence but to end the Constitutional Revolution of 1906. He declared that ‘the constitution was not the last word for them, and whatever was contrary to the Quran, they would oppose it.’ This tendency to raise the violent voice of an authoritative religious tradition as the “legitimate” and “authentic” culture of Iran gave everyone in the early days of the Revolution an idea of what the Islamic Republic would look like. Iran is the only example of an Islamic state installed through a popular revolution, and this duality in the structures of the Islamic Republic of Iran is evident in the title of the Islamic Republic, which refers to an elected republican body with a president and a parliament functioning in the same political structure with the rule of a Faqih. Despite declaring the oneness and brotherhood of all Muslims, the Islamic Republic fosters Iranian nationalism.

Protesters burned photos of the Shah, https://owlcation.com/

Protesters burned photos of the Shah, https://owlcation.com/

Khomeini’s understanding of authority had to come to terms with modern understandings derived from the West, leading to a constitution that gives predominance to Islamic law and authority based on the divine will but also incorporates the will of the people and their sovereignty. This mixture has produced many contradictions, particularly in terms of parliamentary legislation conflicting with Islamic law and the authority of the jurist overriding legitimate constitutional structures. However, many years after the revolution, there is still an absence of an organizational factor to unite the diverse inspirations of Iranians. The practical problem the Islamic Republic faces is that it has two poles: subjecting practical problems to so much religious dispute that solving them becomes secondary, and the danger of secularization of Iranian society. Secularisation is less apparent in domestic politics, where a strict Islamic system is still enforced, and no political parties, factions, or candidates other than those supporting the system are allowed into the political arena, which contradicts democracy.

Conclusion

The Iranian revolution, aimed at establishing Iran as a regional power, has been criticized for fostering Islamic orthodoxy and extremism, leading to the rise of Islamic Jihadists. This has resulted in a weak economy and rising social tensions. Despite significant changes in sectors like education and healthcare, discontent has risen globally. The Western world views the Iranian Revolution as backwards and Islamic, leading to failed wars and the implosion of parts of the Middle East, North Africa, and South Asia. In this scenario, The Iranian government needs to prioritise the existing crises of corruption and lack of personal freedom in the country. The US must also understand Iran’s domestic situation by considering its geopolitical and geostrategic importance in addressing Afghan and Syrian instability. If the constitution remains in force, Islamic republicanism will have practical difficulties and the tension between the “republican” and the “Islamic” will continue. The key question is whether the Islamic Republic can survive its ideological identity by leaving a place for popular sovereignty, or if the divine mandate of velayat-e-faqih puts an end to all hope of a democratic transition in Iran. The quest is still ongoing.

References:

Journal Article:

- Karen Rasler, “Concessions, Repression, and Political Protest in the Iranian Revolution.” American Sociological Review 61, no. 1 (1996): 132–52. https://doi.org/10.2307/2096410.

Online Article:

- Janet Afary, 10th August 2023, “Iranian Revolution’, Encyclopedia Britannica

- Sethu Krishnan M, 23rd October 2020, “Iranian Revolution – How is the Islamic Revolution Connected with the Clash of Civilizations?”, Clear IAS, World History Notes

- Special to People’s World, 11th February 2019,” How did the Iranian Revolution go so far off the rails?”, People’s World

- Jo Adetunji, “Iranian revolution: world’s reactions show that four decades on, tensions remain as high as ever”, February 13, 2019, The Conversation

- Ramin Jahanbegloo, 14th February 2018, “Between ‘Islamic’ and ‘Republic’, What’s Left of the Iranian Revolution?”, The Wire

- Parvez, “Iran 1979: the Islamic revolution that shook the world”, Al Jazeera

Contributor