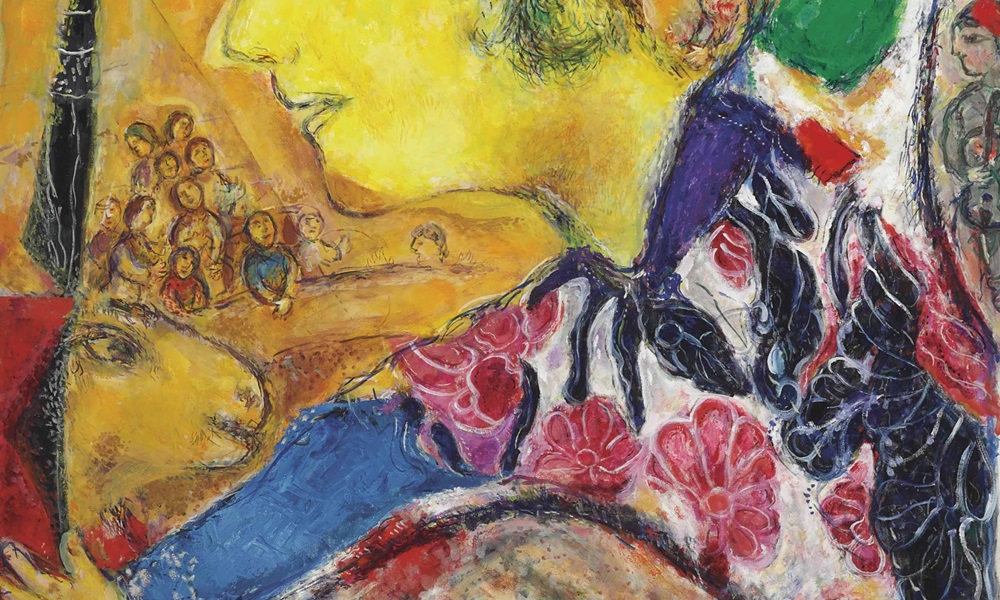

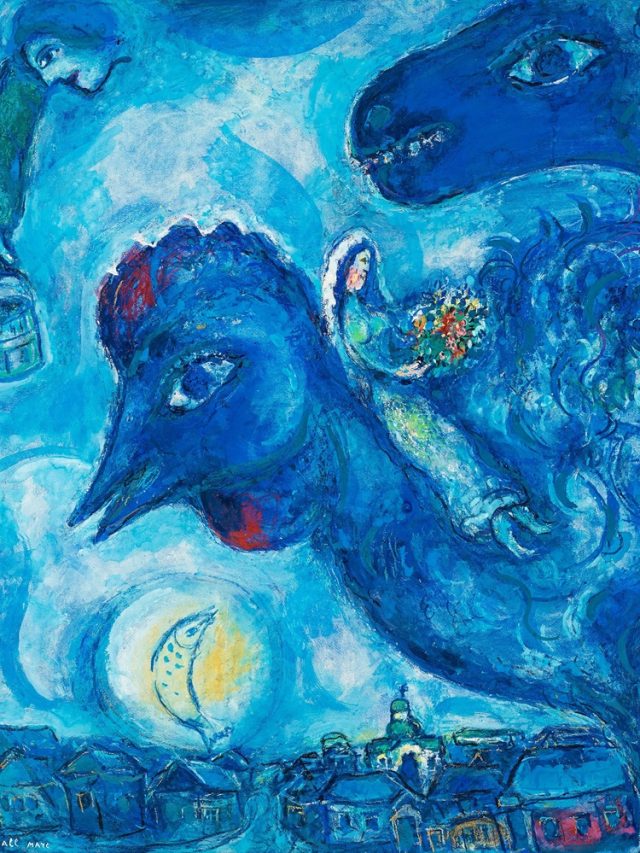

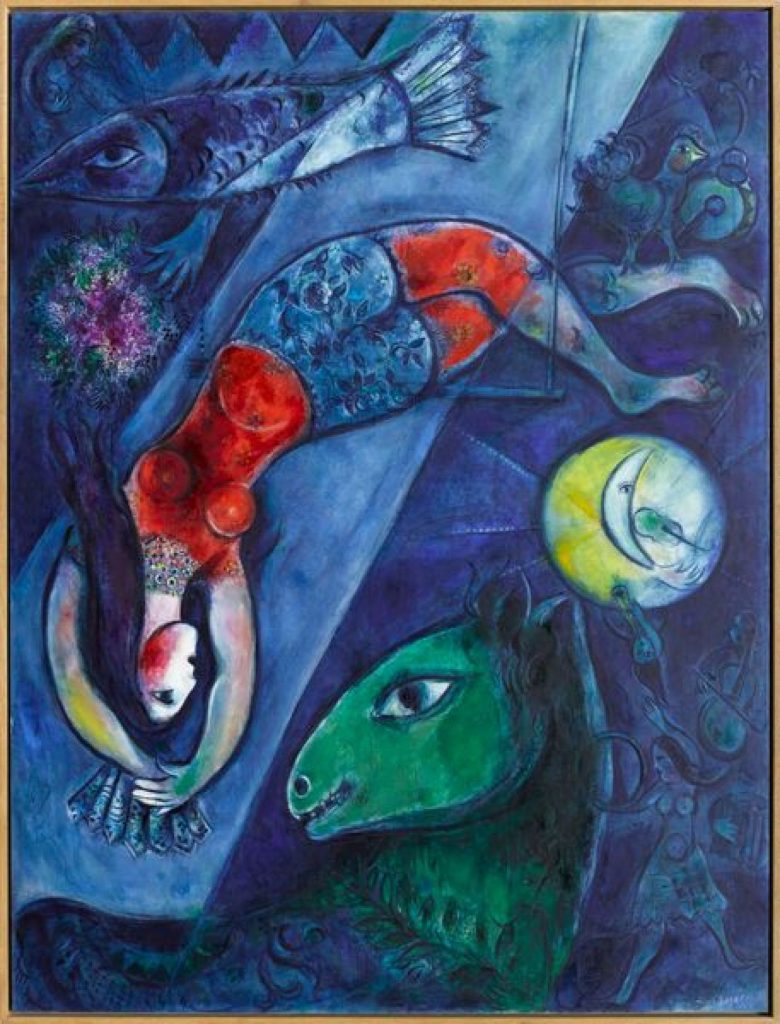

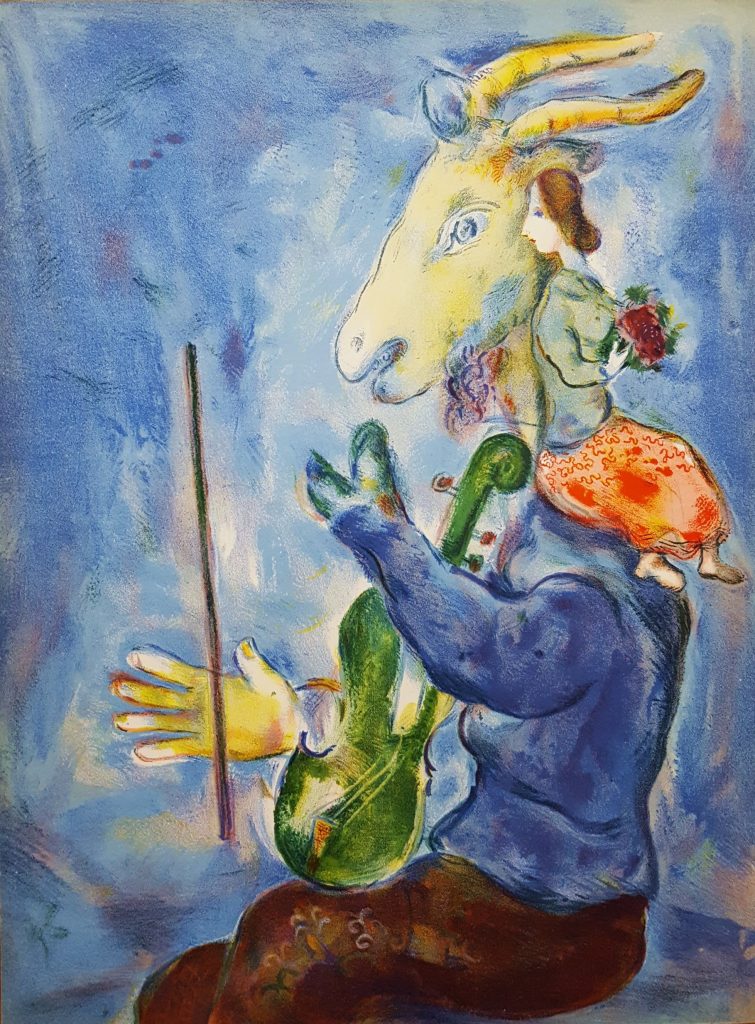

Marc Chagall is a great artist whose canvases reverberate with emotion, mythology, and the essence of dreams inside the colourful tapestry of 20th-century art. Born in Vitebsk, Belarus, in 1887, Chagall travelled across continents and periods in his artistic career, fusing surrealism, cubism, and fauvism into a singular style that eluded classification. Love, religion, and a strong bond with his Jewish background are themes throughout Chagall’s work and are infused into each brushstroke. Chagall painted a universe where lovers glide above rooftops, fiddlers dance joyfully, and angels watch earthly sights with tranquil detachment from the busy streets of Paris to the quiet corners of his hometown. His vivid, vibrant colours and imaginative compositions crafted visual stories beyond simple realism, giving spectators a peek into a world where the supernatural and the real coexist peacefully.

Chagall’s work defies simple classification because many movements, such as surrealism, Symbolism, Cubism, and Fauvism, influenced it. He combined these various forms to create a unique visual language full of vivid hues, dreamy compositions, and poetic meaning. Because of this blending of inspirations, Chagall produced works that spoke to viewers of all ages while being both contemporary and classic. Chagall’s strong ties to his Russian folklore and Jewish background were fundamental to his artistic expression. He aroused feelings of nostalgia and longing for a bygone era with reoccurring themes including floating people, animals, and religious symbols. Chagall’s art has a universal appeal that transcends cultural boundaries and speaks to the human condition because of his ability to infuse ordinary scenes with mythological and spiritual importance.

The intense emotional intensity that Chagall poured into his paintings reflects his experiences with love, loss, displacement, and resiliency. His portrayals of mysterious landscapes, couples floating over rooftops, and musicians serenading the night inspire awe and whimsy in viewers and transport them to a realm where imagination and reality collide. Chagall portrayed temporary joy and grief, characterising the human experience with his expressive brushwork and evocative use of colour. Modern art evolved due to Chagall’s inventive compositional techniques and his investigation of the subconscious. Artists like Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and Mark Rothko were affected by his use of solid colours and symbolic imagery, and they respected his capacity to express profound emotional truths via painting. Future artists will be able to explore new forms of artistic expression thanks to Chagall’s willingness to experiment with both form and content.

Life and Work of Chagal

“Remember,” he said, “that my painting is not European. It is partly Oriental. Colour and substance are what count for me. I am not interested in the formal aspects of pictures.” -Chagall

In his words and paintings, Chagall uses poetic licence and approaches “the formal aspects of pictures” in a particular way. But since the start of his career, colour and substance have unquestionably been two of the most critical components of his work. “I left Russia in 1910 because of the dead colour of Russian painting, and I left again in 1922 for the same reason,” he added, alluding to the academic art that flourished under the czars and was formally embraced by the Soviet authorities after a modernist interlude.

Chagall’s self-identification as an ‘abstract’ colourist is more than a declaration. It’s a profound statement about his use of colour as a means of expression. His art goes beyond merely painting a face blue, a tree red, or the sky yellow. His claim to be an “abstract” colourist has been made often, and by this, he means much more than just the fact that he has always been willing to summarise; Chagall attempts to make us see and experience his world—first as shimmering material imbued with consciousness and spirit, and then as an assortment of pictures and potential topic for literary allegory. He occasionally starts work with just a few colour zones smeared throughout the whole surface in various levels of transparency. The outcome is frequently the same even if this process is not followed: one rarely feels that colour is simultaneously spatial and fills in prior forms.

‘The elements that go into the making of a colourist, particularly as fine a one as this, are mysterious. Chagall gives excellent credit for developing his talent to the influence of the light and colour of Paris and the French countryside. “My Russian pictures,” he has written, “were without light. In Russia, everything is sombre, brown, and grey. When I arrived in France, I was struck by the shimmer of the colour and the play of the light, and I found what I had been unthinkingly seeking—a refinement of matter and wild colour. My familiar sources remained the same: I did not become a Parisian, but now the light came from the outside.” There is some exaggeration here; the early Russian pictures are by no means entirely gloomy, and in 1906, four years before the journey to Paris, Chagall was already considered an eccentric by his teacher in Vitebsk because of a habit of painting in violet: “It seemed so daring that from then on I attended his school free of charge….” But his palette indeed became brighter shortly after he arrived in France. Leon Bakst, his teacher in St. Petersburg, came to Paris in 191 1 with Diaghilev’s ballet company and noticed the brightness immediately: “Now,” he said, “your colours sing.” Three years later, the poet Guillaume Apollinaire wrote of Chagall as “a gifted colourist who yields to every suggestion of his mystic, heathen fantasy, writes Roy McMullen in his book, The World of Marc Chagall.

According to Roy McMullen, he could be more precise in his theorizing about depicted space. He maintains that “what is called perspective” does not necessarily add “depth” to a picture, but he leaves hanging the question of how metaphorically he wants the word “depth” to be taken. He denies that a Cubist “third dimension,” obtained by warping the facets of represented objects into the plane of the canvas, can afford “a view of the subject from all sides,” again, his terms can have more than one meaning. He speculates about pictorial space that is neither Euclidean nor, strictly speaking, visible. Still, he does not quite commit to such space: “Perhaps another dimension exists—a fourth, a fifth, not only of the eye. And this dimension is not just ‘literature,’ ‘symbolism,’ or ‘poetry’ in art. Maybe it is something more abstract, not in the sense of being unreal but of being more accessible. It may be something that intuitively gives birth to a scale of plastic and psychic contrasts…”

The numerous images that use montage to juxtapose disparate images and achieve “plastic and psychic contrasts” are where Chagall’s space is most obviously cinematic, albeit in a reasonably antiquated sense; most of the pieces included in this book can be used as examples. However, a second glance at these paintings usually reveals a more nuanced and striking analogy; the space can be seen flowing, jumping, coming, going, or spreading out in calm lagoons (sometimes in tandem with its fellow concept, time) (with the help of coloured “tissue” and light “from behind the canvas”) as it does under the tutelage of an Antonioni or a Resnais.

In Chagall’s work, the dreamer is often a lover; when this happens, part of the picture space becomes sexual, surreal, and cinematic. This concept could be likened to ‘sexual territories’ that expert bird and animal observers have been investigating recently. These ‘territories’ refer to areas of intense activity or focus, and in Chagall’s work, they represent the passionate and intimate aspects of the human experience. Chagall’s art could also be compared to a region swept by a romantic radar, a metaphor for his paintings’ intense emotional and romantic elements. Typically, Chagall can work in both categories at the same time. He draws attention to the solid, flat surfaces in The Green Horse, Jacob’s Dream, and Window in the Sky, to name a few works that we are starting to get sufficiently familiar with, by using a densely coloured substance that is brushed on and by refusing to arrange his material by the rules of perspective.

Nonetheless, he places the pieces in traditional perspective and uses colour, light, and overlapping parts to create further distance illusions. Thus, the images can be parts of impenetrable walls one moment, openings in walls the next, or both at once. They resemble exquisitely smeared windows that can be viewed outside or inside. They are both outgoing and introverted, to put it simply.

Fostering a Family of Images

Marc Chagall consistently acknowledged his native Russia, particularly Vitebsk, his hometown, as “the soil which had nourished the roots of [his] art” throughout his career. But at twenty-three, Chagall began to believe that the “lumièreliberté” of Paris was the only place where his work could flourish. As many observers have noted, Chagall’s move from St Petersburg to Paris in the summer of 1910 marked a turning point in his artistic growth. The crucial window Chagall’s departure from Paris provides for our comprehension of the artist’s Jewish identity is frequently missed.

Chagall’s artistic reflections heavily rely on the crucifixion out of all the possible images found in the New Testament. This chapter will look at how he approaches the crucifixion leading up to and throughout World War II and then how he changes how he uses the motif in his paintings following the conflict. By analysing a set of three paintings finished in the late 1940s, I argue that Chagall realised the crucifixion’s full potential as an iconographic space to explore and establish his position in Western art history in the early years following the war.

Impressionism, in particular, marked the beginning of the evolution of contemporary art. Previous schools and trends, such as Neo-Classicism with painters David and Ingres, Romanticism with Delacroix, and Naturalism with Courbet, all stayed primarily in the ideological domains, and this ideology is not different from the ideology prior. Piero de la Francesca, an early artist, developed chiaroscuro, a theory of light and shade, for himself even before the Renaissance, without realising that the Impressionists of the late nineteenth century changed the essence of the image by bringing in a new understanding of light.

A simple sketch became a picture, and fleeting thoughts became a more stable image, thanks to the Impressionists’ pursuit of freedom and creativity. As they freed themselves from the confines of convention and cleaned the colour palette, they appeared to be making fun of the sweeping compositions of the academic masters who came before them. Their use of every shade in the rainbow mirrored scientific findings and gave the painting’s surface a lively vitality. Although this movement was new, young, faithful, and fresh, some saw it as shallow and flimsy.