Vandana Shukla

Humour has been an essential element of art since the earliest times. From ancient cave paintings to contemporary installations, artists have used humour to engage, entertain, and enlighten their audiences. Once we take a closer glimpse into Indian art, we find out that it also hosts a rich history of humour that is fascinating to follow, from many humourous frescoes to satirical caricatures.

Anecdotal Humour in plastic arts

Laughter comes as naturally to humans, as does anger or pathos. All human expressions have occasional humorous anecdotes; to kill monotony.

In art, though humour is inexplicable. It can be decipherable; subject to perceptibility.

Long before Indian art acquired the stiff-upper-lip stance of modernism; it was already defined by the principles of the nine rasas. The nine rasas are a spectrum of human emotions that outline the aesthetics of Indian art. According to Bharat Muni’s Natyashastra these nine rasas are; erotic, comic, pathetic, furious, heroic, terrible, odious, marvelous and quietist.

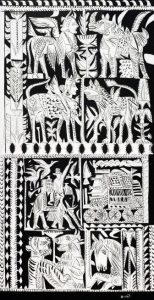

Courtsey- Krishnakshi Kashyap

Hasya or humour has been used as an integral rasa to complete the spectrum of human expression since the first lines were sketched in a cave by the primitive man.

All genres of art incorporated humour.

I witnessed the oldest expression of humour in plastic art dating back to 2300 BCE, at Peshawar Museum, in Pakistan. Found in Mohenjo-Daro excavations; a cluster of clay figurines show all the possible facial expressions humans have. These moulds include a few quirky faces too, to arouse amusement and laughter. At about 2300 BCE, people observed what could be humorous and found a way to express it.

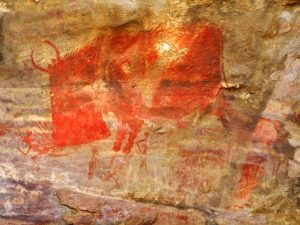

From Lascaux caves of France to Bhimbetka of Bhopal, cave paintings show that the sense of humour of the primitive man was no different from that of the man of the 21st century.

With time, the forms and contents change; finding newer ways to express the underlying emotion of hasya. If TikTok defines what is humorous in the 21st century digital era, Paleolithic and Mesolithic period art had humour of its own kind. A kind of mocking of the human will against the might of the animal world.

A 2018 report of a geologist from New Mexico refers to a series of fossilised footprints found in New Mexico. They are the prints of a giant sloth, with much smaller human footprints inside them. Suggesting, that the humans were deliberately matching the sloth’s strides; following it from a close distance. Or, were they mocking it?

Life, as it was, found expression in the raw cave paintings and clay moulds in ancient times. In the cave paintings of Bhimetka, which have layers of paintings; painted at different points in time; several facets of human and animal life are drawn with a chuckle. Women digging out rats from the holes, an elephant painted within the outline of a deer, suggest, a humorous approach of humans to their surroundings. In one of the paintings, a horned boar of enormous size, with fur on the head is chasing a tiny human figure and a crab. The human figure and the crab are fleeing the giant horned boar. The technique of juxtaposing the human with a crab is brilliant; it is used in caricatures to create humour even today.

Courtesy- Wiki Commons

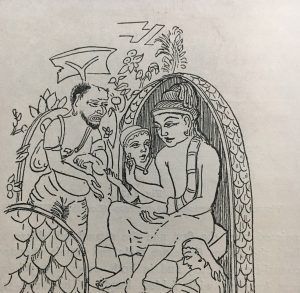

One finds many amusing illustrations from Jataka tales, that deals with the previous lives of the Buddha. In one of the illustrations from the Jataka in Bharhut sculptures in Madhya Pradesh, of the Sunga period, dating back to mid-2nd century BCE, a monkey is shown extracting a hair from a man’s nose. The hair is held by a pile which is pulled by an elephant. The elephant seems to have found the job strenuous. Therefore, the monkeys seem to encourage him by playing the trumpets and drums. One monkey is seen even striking the elephant with a stick, another is biting his ear. The whole illustration is conceptualised following the Indian tradition of using the animals allegorically; to give a profound message. Here, perhaps the message follows the adage of digging a mountain to find a rat.

In another roundel on a balustrade, a group of monkeys is shown taking out an elephant, in a procession. These sculptures reflect the peculiarities of the times with an element of humour directed at the social oddities; an elephant being driven by the monkeys. Perhaps ridiculing the power game run by mediocrity.

Even though the expression of humour in art is time and culture specific; it carries a certain universality. Therein lies its timeless appeal.

The comical element was often depicted using the motif of animals. In the open-air Pallava period relief (7th century AD) known as The Descent of the Ganges, at Mamallapuram, where Bhagiratha is doing penance with uplifted arms, a cat is shown in a similar posture with paws outstretched upwards. Some rats are shown nearby playing about or sleeping fearlessly. The sculpture seems to make an oblique reference to pretentious devotion. The artist seems to be ridiculing it.

Courtesy- Ken Kawasaki

In Khajuraho temples (885 to 1000 AD) amidst the beautifully carved sensual sculptures, one finds a few sculptures that depict comical situations. In one of the sculptures, a couple, who is trying to get intimate is disturbed by a monkey, who is pulling the walking stick of the man, perhaps to distract him.

Humour is used using utmost economy though. It is never overdone to kill the dominant emotion, which, at Khajuraho, is shringara.

In the Sun temple of Konark, mid-13th century AD, one can see a number of humorous depictions around daily life. These are comical in a culture and time specific manner. Monkeys are shown pilfering sweets from a woman’s basket. Other monkeys are shown trying to get on to the head of the woman in a funny manner. The expressions on the faces of the monkeys are comical. Such scenes, common among the markets of that time must evoke laughter in real-life situations.

The solemn nature of sculptures is interspersed with comical or the humorous, to kill sameness. Humour is usually not related to the religious or mythological theme of the temples, they are found in.

Terracotta, or, the poor man’s sculpture, too, is a great source of social history in India. Their lively naturalism and humour carry a comical strain. One terracotta plaque of the Gupta period, 5th century AD, from Mathura shows a woman playfully pulling the scarf of a court jester (vidushaka). The vidushaka is wearing a conical cap and is making funny gestures. In another plaque, also from Gupta period, the Ganas of Shiva are shown engaged in helping themselves with two basketfuls of sweets, they are shown as nude, corpulent dwarfs with conspicuous genitals. Although it depicts a scene from Daksha yajna of the Mahabharata, this scene has no religious significance. It is of pure fun and frolic intended to amuse simple people. It may have popular appeal for the village folks who might like to recreate such scenes.

Dwarves were also used as a tool to create humour (this was long before body-shaming became a moral crime). At Sanchi, Mathura and Pithalkhora in Andhra, Ellora, Badami Sarnath, Mamallapuram and several other places from 2nd century BC to 9th century AD, dwarves are used as characters signifying different traits. Their imaginative stylisation and expressive exaggeration and quaintness adds comical appeal to the otherwise sombre art of the times.

Humorous Characters in Frescos and Paintings

Humour and satire are used anecdotally in ancient Indian art. The theme or subject of an artwork is never treated exclusively with humour. Seeing the richness and diversity of themes and ingenuity of expression in our art- it is a bit baffling.

Because most art forms evolved around religion and myths, perhaps humour was not given prominence to avoid dilution. Later, the arts were patronized by the kings and nawabs. The subject matter of the art was always sombre and aimed at the evolution of the human soul. Whereas humour was lifted from the ordinariness of life; with its deformities and shortcomings. Greed, avarice, and sloth are ridiculed in the artworks, and so are hypocrisy and shallowness.

Humour, lifted from the ordinary, adds a kind of folk element to the otherwise classicist arts in India.

Characters like Kumbhakarna, Narad and gluttons are often ridiculed in visual arts. Such characters also offer an opportunity for exaggeration; a device used for caricatures. Then, there are socially unacceptable traits; like a dominant woman or a sadhu with a temper. Their depiction is used to evoke laughter. One finds the motifs and images used for creating humour are repetitive over a long period, and expressions and mediums differ.

Unlike the sculptures and terracotta art where humour was aroused by recreating anecdotes, selected from day-to-day life for their quirkiness; classical Indian pictorial art is full of character studies, that are humorous. Their treatment is detailed.

Perhaps the oldest such painting is found in a scene depicted in cave # 17 at Ajanta (5th century AD), where the Bodhisattva, as a prince, donates gold coins to a Brahmin named Jujaka. The avaricious character of Jujaka is portrayed in humorous details; a thin beard, broken teeth, a balding head with a few wiry hairs hanging like threads and the expression of greed pouring out of his face; to bring a smile to the viewer’s face.

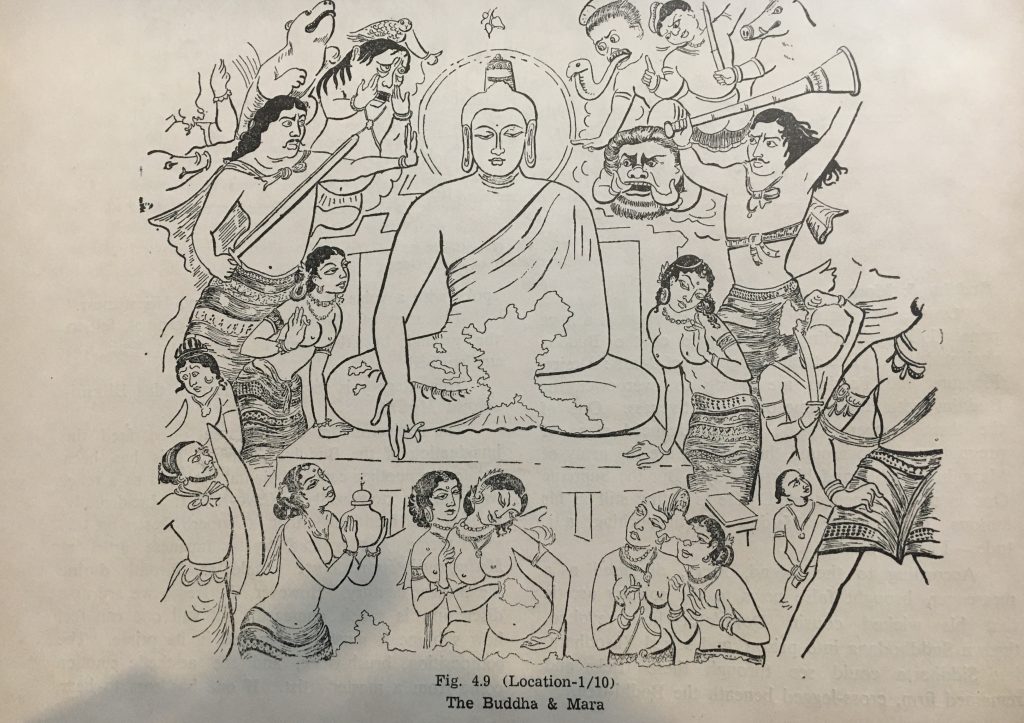

To add vivacity to the sombre themes of these paintings, which are, at times didactic in nature, the artists have used many strange-looking insects, animals and dreadful forms of Mara, who is trying to harm the Bodhisattva in these paintings. The demon’s army is painted as caricatures to create humour.

After the life-like wall paintings of Ajanta, for centuries, there was no trace of paintings in India. The next line of paintings, with a touch of humour, is found in miniature art, around the 16th, and 17th centuries.

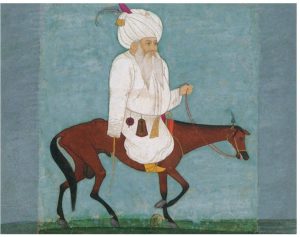

Here again, we find that funny characters are introduced. In Mughal miniature art, the character of Mulla- do- pyaza, the court buffoon, is depicted dressed gorgeously in a large turban, riding a rickety donkey. The name Mulla-do-pyaza itself is humorous, connoting the over-enthusiasm of a new convert. Another painting of around the same period shows a fat woman, riding a camel. Carrying a pot of sweets, perhaps eager to eat them; she is harassed by flies.

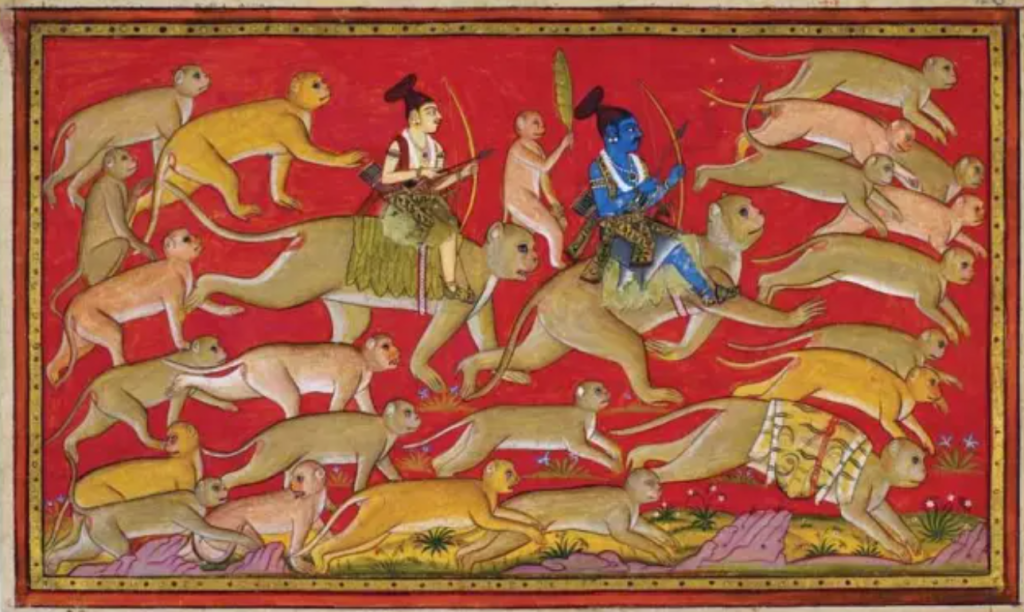

In the miniature paintings of Mewar, of the early 17th century, images from the Ramayana and other religious myths, portray a few characters to evoke humour.

In the Ramayana Set displayed at Bharat Kala Bhawan, Varanasi, a humorous scene is depicted around Kumbhakarna in a painting titled Kumbhakarna Asleep. The war with Ram was at a critical juncture and Ravan was trying to wake up his brother, who was a great warrior apart from a legendary sleeper, to come to his help. Kumbhakarna is shown sleeping in a courtyard. A veritable army is shown trying to bring him back to an awakened state; with all sorts of musical instruments—drums and cymbals—being played with gusto, close to his ears. Some dogs are barking, sitting on his belly; the service of an elephant is sought to trample his feet; a man is discharging gunshots in the air, yet, Kumbhakarna is shown undisturbed— deep in his sleep.

The clever use of gunshots in this mythical depiction reflects the innovative approach adopted by miniature artists; to create fresh boundaries around myths.

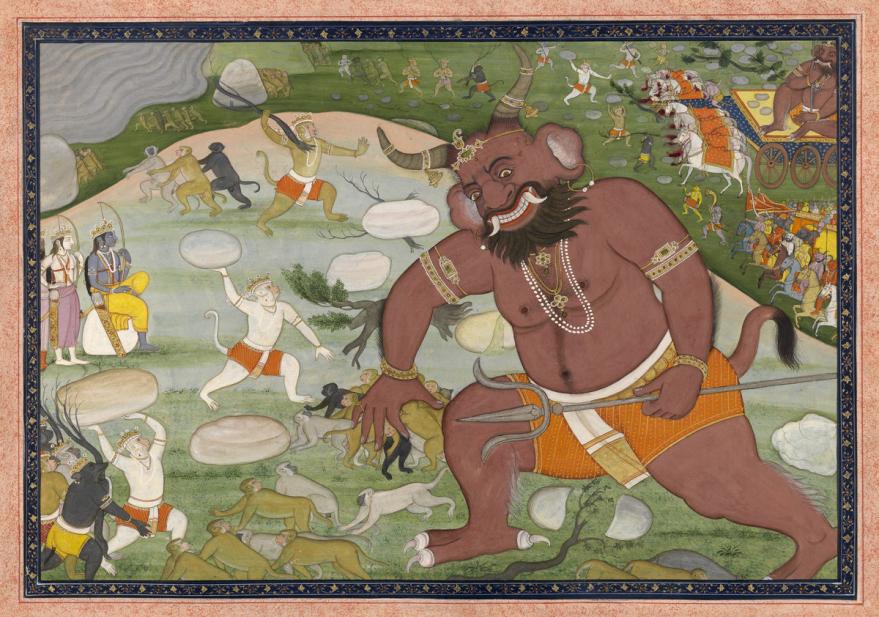

In another painting from the Deccan School, 19th century, titled Ram and Ravan at War, Kumbhakarna is at war, with Hanuman and the army of monkeys. Some of the monkeys hang on to Kumbh Karan’s moustache, a few are coming out of his nostrils, a few sit on his tongue and many more are trying to pull off his headgear, in a funny manner.

Another humorous character is Triloka Khatri, a bridegroom from Bikaner, around the 18th century. It shows an old man with an enormous paunch, and huge protruding lips under a long moustache but magnificently dressed as a groom. The funniest thing is, flies are buzzing around his head, and a few enter his half-open mouth, as he breathes. It is a satire on the lustful old, rich men— ever-willing to get a young bride.

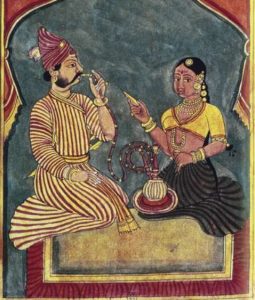

Opium eaters are used as caricatures across miniature art schools, in a manner dwarves are used in sculptures.

Pahadi paintings use humour in abundance, often targeting Pahadi tribes and their idiosyncrasies. The Gaddi tribes, who live in the wild to raise sheep, known for their lack of worldliness, are shown haggling for little things at their halting stations on their mountain tracks. Ridiculed for their unrealistic bargaining, in a small mural of the 18th century, shown in the old palace of Kullu, two Gaddis are shown slapping each other, holding each other’s moustaches. In another Mughal painting of the 19th century, two sadhus are shown doing the same.

A Gaddi, known for haggling hard for petty purchases is shown having a heated argument with a shopkeeper, while three others are getting into a scuffle, in another painting. The artist seems to be mocking the simple folks and their lack of sophistication.

Pahadi paintings from the 18th and 19th centuries, displayed at Chandigarh and Lahore Museum, offer an interesting study of humour. A wedding party is shown where men afflicted with goitre, with their deformed figures, are shown dancing and singing. In present times, it would be politically wrong to show deformity as a humourous subject. Another miniature depicts a rotund bridegroom with goitre riding a famished donkey. One more painting in the same museum shows a domestic scene where a woman is giving an erring husband a good thrashing with shoes.

The social oddities were used as tools to evoke humour; very few paintings lampoon the religious heads, and almost none that I have seen show the kings or patrons in a comical manner. Even satire is politically correct.

The place enjoyed by eroticism in classical Indian art was never accorded to humour. It raises questions about the freedom enjoyed by the artists to express social reality and the ability of the people to absorb it.

Mocking the white sahebs and thereafter

Through the cultural renaissance of India, especially in Bengal, artists were targeting social evils. Social satire emerged as a major theme in art, replacing the monkeys and donkeys, to tickle the laughing bone.

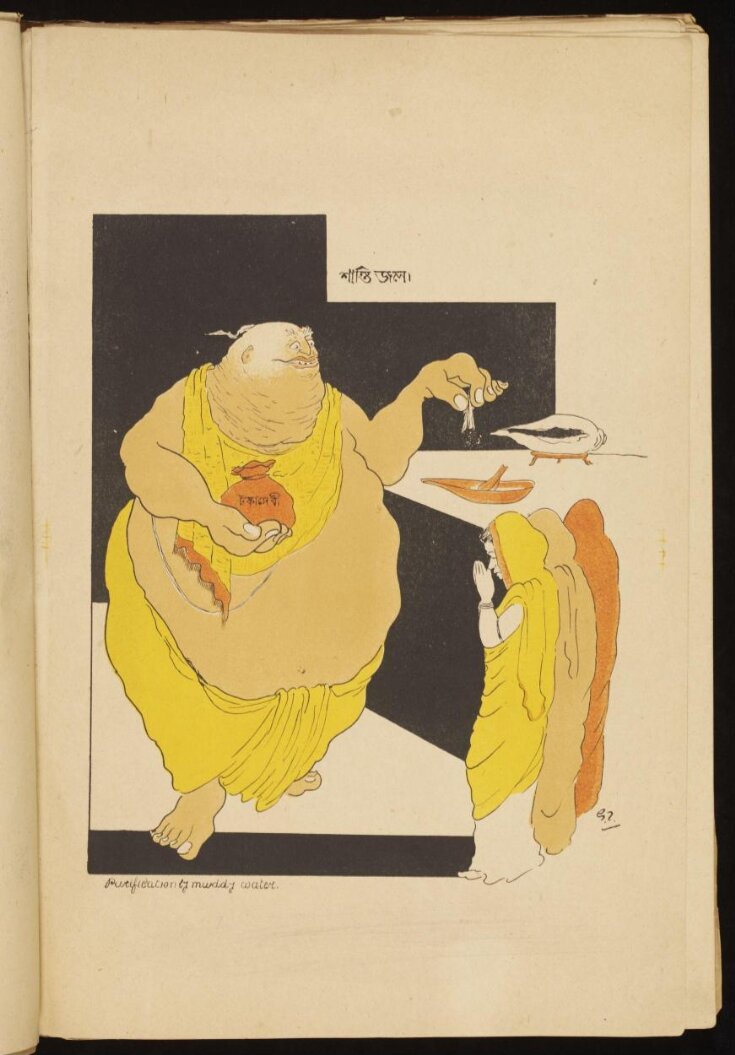

The caricatures of Gaganendranath Tagore (1867-1938) place the opposites and the odd in the same frame. The Brahmins and rich Parsis and Baniyas are lampooned. Works like “Purification by Muddy Water” place tiny and timid women against a very fat Brahmin, who is towering over them-offering muddy water for their purification. Respecting women is another satire poked at the emergence of the so-called educated modern man and his hypocrisies. “Realm of the Absurd”, as the title suggests, has several such references. These works are direct, often supported by a title to make things obvious.

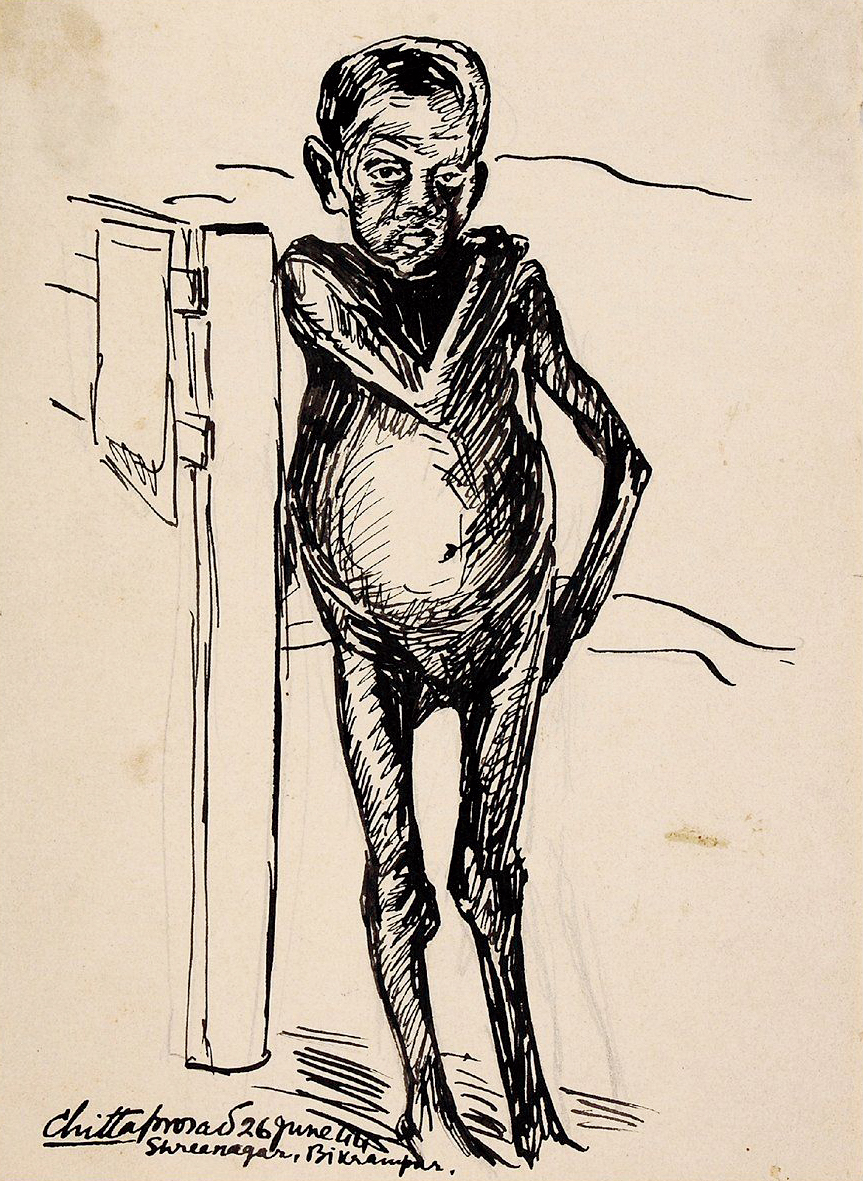

Chittaprosad (1915-1978) also refuses to use subtlety to blunt his political cartoons; aimed to provoke the white sahebs. He had seen and suffered the starkness of the Bengal famine under the British. A retrospective of his works, at Kochi Biennale, presented the audacity of his spirit that prompted the British to seize and destroy most of his works. His treatment of the oppressor’s stubborn refusal to see the reality, at times, borders the comic. In one of his works, the white sahebs; happy, fat and content– are shown with their packed bags going home, looking at the famished skeletal figures and a pile of skeletons, with a grin, in a manner of saying- good riddance. In another work of his, a fat-rich family is shown standing opposite a child, who too has a fat belly, but due to Kwashiorkor, a disease triggered by prolonged hunger that causes a swollen belly due to lack of nutrients in the body.

Humour brings a subversive quality to these works. The famished men and women with their enlarged eyes and the cage of ribs that house a normal, well-fed, imaginary human being, of Chittaprosad or, the fat bellies of Gaganendranath’s cartoons; reflect the refusal to submit to the existing systems—political and social.

Post-independence, the focus shifted to the emerging Indian identity and its absurdities. The target of ridicule shifted from the white saheb to the politicians, the men of power and the rich.

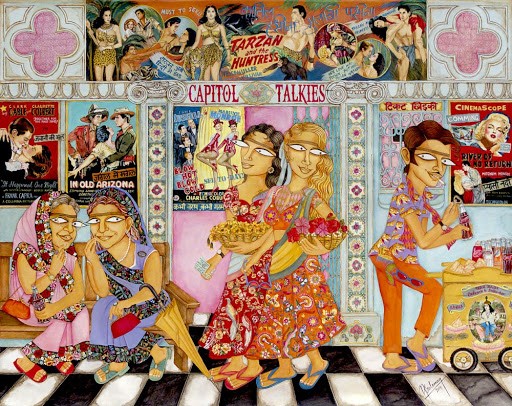

With his witty sense of humour, K G Subramanyan created playful, witty and erotically charged pictorial fictions around the idea of India’s emerging culture and its negotiations with other dominant cultures.

Subramanyan finds it funny that in a culture in which gods feel the need to reincarnate themselves in order to save humans; the imperfections of the culture provide room for him to experiment with the icons. His works create complex reflections by juxtaposing icons of culture against ordinary humans and animals. Placing a monkey against a Hanuman figure or an ordinary woman against Durga—to show each other as reflections—of good and evil–depicting conflicts and imperfections of human imagination in conceptualizing icons. ‘War of the relics’, a tongue in cheek comment on the similarities across cultures is another iconic work of his. Subramanyan’s treatment of the complexities of cultures and identities in pictorial narratives introduced sophistication that only humour could bring about in art.

The contradictions of the emerging modern society; the growing middle class with its confused moral compass; contemporary realities and the global aspirations of local cultures become exaggerated in some of the works of the modernists. These interplays and incongruities emphasize humour.

Bhupen Khakhar channels humour to leave subversive impressions on our sanitised moral universes. He contextualised his homosexuality to pierce through the accepted myths of history, religion and culture, with humour. In Two Men in Benares, he places two gay men, aroused sexually, in the backdrop of the holy city. In another painting; a scene of a family wedding; two men are shown holding hands, in an audacious mischief. Their hands seem to grow out of the frame of the family wedding. The wit, with which he expressed gay issues and related morality in You Can’t Please All; weaving the sacred with the profane, imaginary with the mundane, in an idiom that is both humorous and profound, his scathing satire created a landmark.

Bhupen Khakhar, Two Men in Benares, oil on canvas, 1982, Sothebys.

F N Souza’s macabre caricatures may not appear comical or humorous; a strand of irony runs through them.

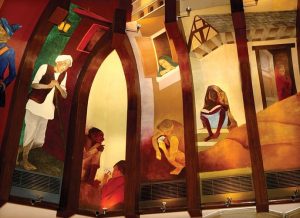

Krishen Khanna revived humour in the tradition of public art. In the mural paintings on the 4000 square feet dome like space of ITC Maurya, New Delhi, he created several scenes picked from ordinary life, which are presented with a humorous twist.

Mural by Krishen Khanna at ITC Maurya, New Delhi. Courtsey Luxe Beat Magazine.

In a place surrounded by mourners, sitting next to a dead-body, Mulk Raj Anand, noted author and Khanna’s friend is seen discussing art and aesthetics; somebody is picking pocket out of a man going to a mosque, Geeta Kapoor, the famous art critic, is walking while someone stares at her– she is holding a book titled ‘What Ails Indian Art.’ There are sahebs and mem sahebs, riding atop elephant; a symbol of their erstwhile Raj.

Then there is the ubiquitous dhaba, where Khushwant Singh is serving tea and Mulk Raj Anand is chewing a chicken bone. Temples, mosques, yatras—pilgrimages—an integral part of Indian civilisation, people co-existing with dogs, goats, monkeys, elephants and tigers complete the slice of life. A few monkeys are mischievous, removing cap from a person’s head, also a reminder of Panchatantra tales. The artists in palaeolithic period too showed animals co-existing with humans.

Khanna also picks the oddities of human behaviour in sombre situations—a woman is shown scratching her ear outside a temple, a man is sitting beside a sleeping dog, as though watching over it.

Amit Ambalal paints parodies; striking a balance between surprise and humour. The ponder-worthy anecdotes of his works are salvaged from day-to-day life, with a chuckle. A calf looks longingly at the udders while a man takes the feed— crouched inside her stomach; a tiger licks pink tulips. In a painting titled Root Canal, two cranes are shown sucking roots with their beaks; the beaks turn into drills.

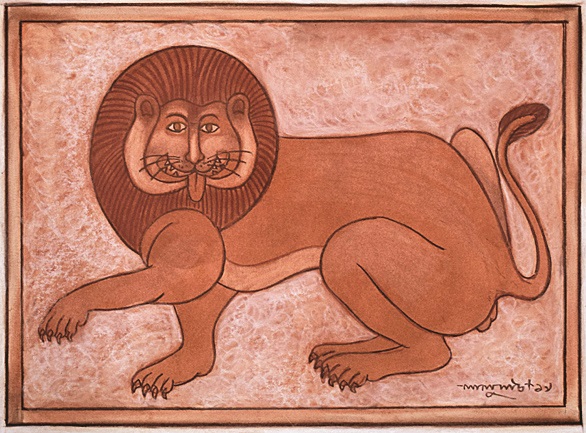

Apart from his witty variations of the Bengal school’s bahus and bibis, Lalu Prasad Shaw also dares the viewers with a twist, for a chuckle. The caricatures of the bhadralok, men with a goatee and women with a ponytail, with strange nasal bones apart, in one of his works a lion is sticking out his tongue secretly laughing at the viewer who is looking at the works in seriousness. It is as if the guarding sculptures of a temple have come to life, scorning the milling crowds.

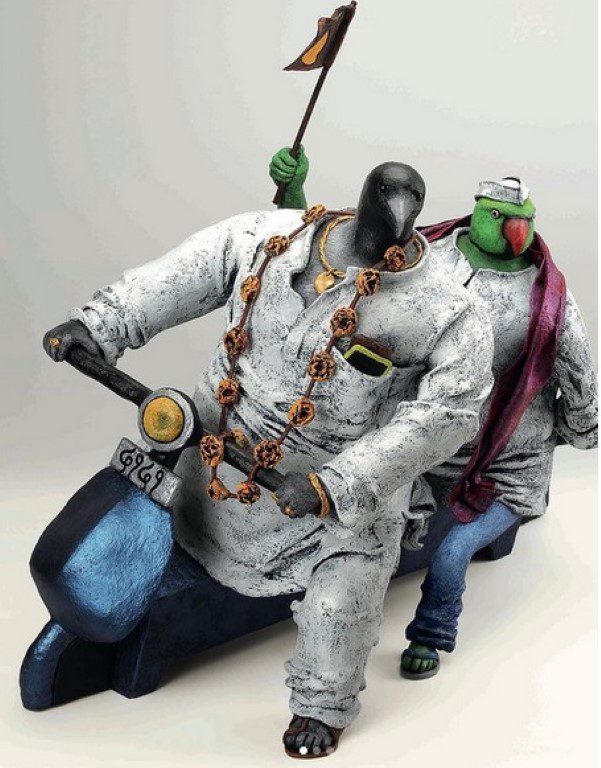

Postmodern humour in the vernacular

Since the time man began to express himself by painting the walls of a cave, humour was used to express what could not be said otherwise; ridicule is used to critique the times.

Humour was made pivotal to Indian art by the post-modernists; it was not an invention of the post-modernists though.

What does humour contribute to a work of art? One may ask, how does humour in art differ when compared to the slapstick comedy in Bollywood films or the humour of stand-up comedians? What happens when art takes on comedy, parody, and satire; not necessarily for laughter but to a point of ponder; to something ‘beyond language’: as Duchamp would suggest. Perhaps, an intersection of all these divergent forms creates humour in Art to salvage the unsaid. To enliven the dead. To tickle the thinking.

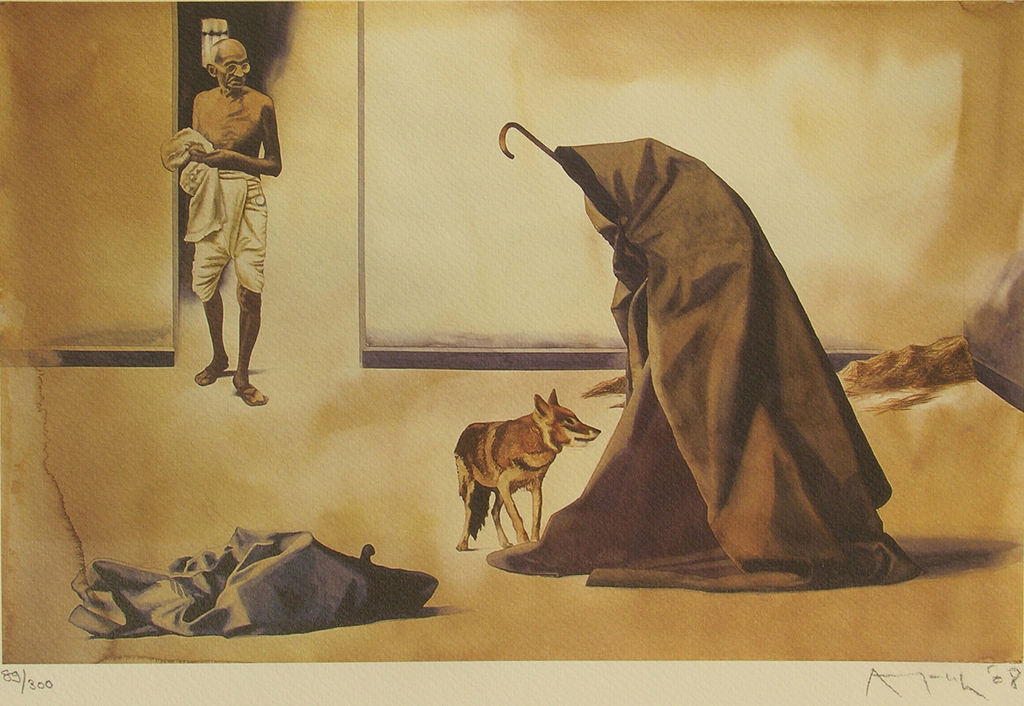

Artists periodically used humour, but Atul Dodiya started to bring humour blatantly to solo exhibitions. He dared to go beyond the obvious ‘fun’; his series on Bollywood and Gandhi, layered with history, geography, politics, media, cinema, art, billboards, tribute and nostalgia blends kitsch with wit and humour. One of his iconic works titled ‘Portrait of a Dealer’ features iconic villains from Bollywood; Pran to Prem Chopra, Madan Puri, Jeevan, Kanhaiya Lal, Gulshan Grover and others.

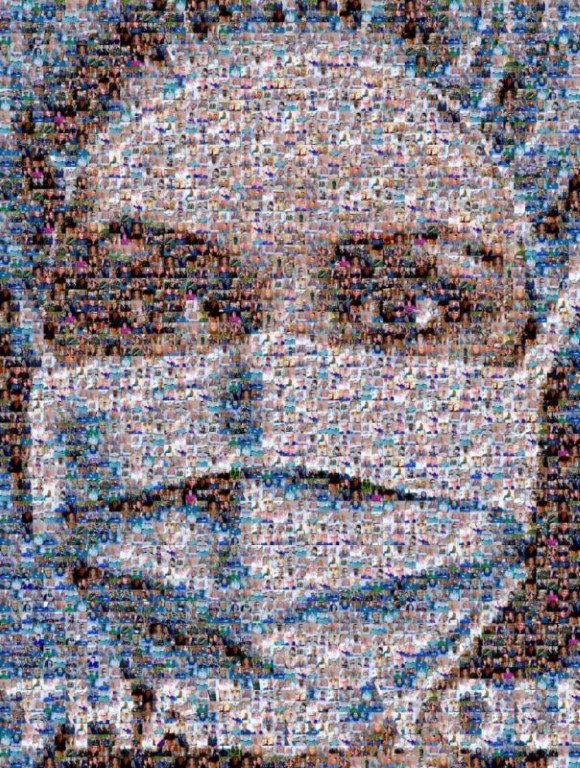

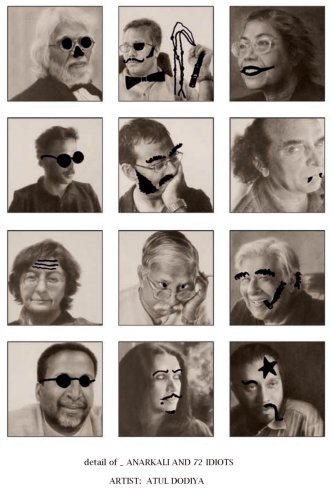

Inspired by Duchamp’s Mona Lisa’s reproduction that the artist had painted with a moustache; raising questions about formal beauty and how we see the history of art; Dodiya launched a prank on a catalogue of artist’s portraits he had painted—by affixing Hitler cut moustache, dark glasses, horns, bindis, goatees or sideburns. He did not spare senior artists like Krishen Khanna, Akbar Padamsee, Hussain, Jehangir Sabavala and Raza. The set of images titled Anarkali and 72 Idiots became a part of the show Sub Plots: Laughing in the Vernacular, at NGMA, Mumbai, in which 24 artists engaged at different levels — questioning or disrupting the status quo; injecting absurdities; highlighting tensions, and sometimes ridiculing the times we are living in.

As fresh subtexts entered the art space- around globalised cultures, women’s rights, urban, upwardly mobile prototypes, highlighting oddities of our times, it was also expanding the scope of humour in art. Manjunath Kamath uses the interiors of middle-class houses to unveil the unconscious where universes coexist in uncanny juxtapositions; Superman, Banksy’s pink elephant, as well as sadhus and mythical characters, coexist in this surreal space. His brightly coloured digital collages create imaginary landscapes where diverse cultural influences and realities collide to capture the dreams of middle-class households.

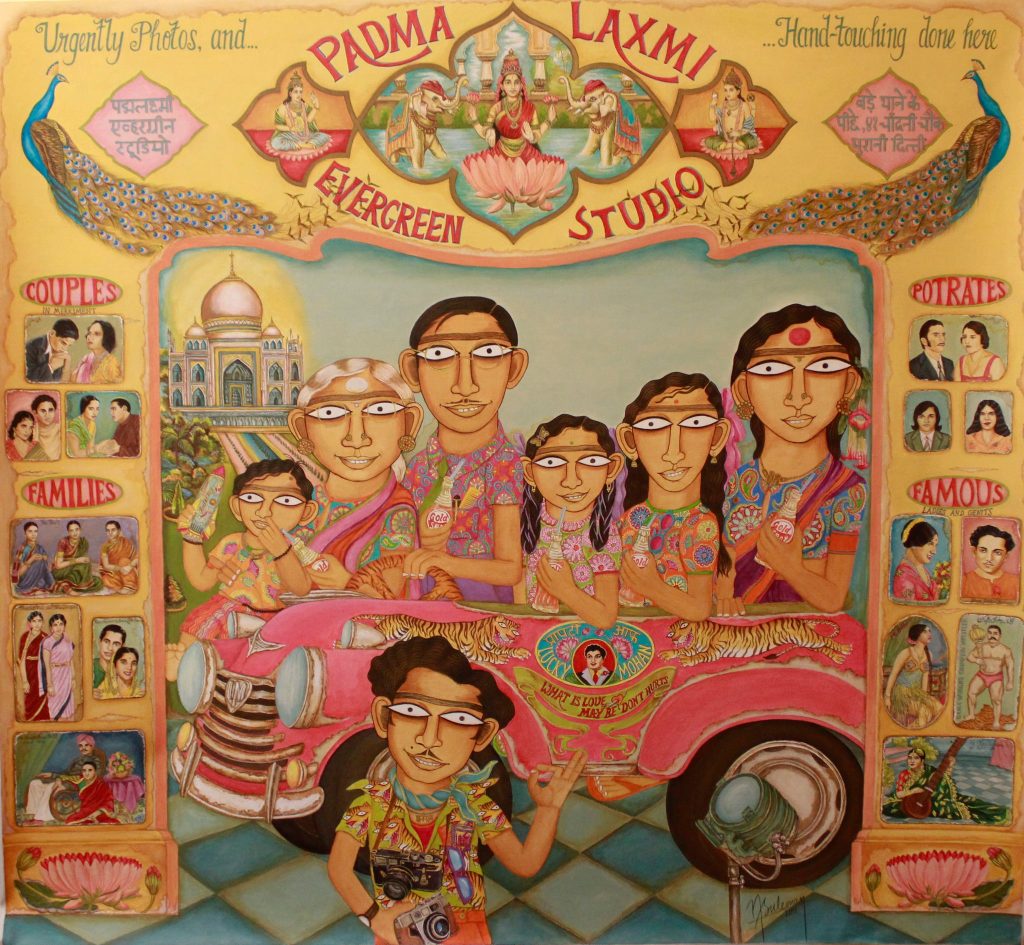

Nilofer Suleman, a Bangalore-based artist’s narratives weave together fantastical sights and sounds of roadside Romeos, popular culture and the intimacy of chai stalls in her brightly coloured kitsch. Cherubs share space with the most revered of the Hindu pantheon in a La Paris Sita Ram Studio. Goddess of wealth, Laxmi, stands nonplussed emerging out of a damp wall, as though looking for an abode of better comfort. A woman buying fish has tigers eyeing the fish from her choli print. Here, Fresh Fish is sold since 1976. You cannot miss the cell phone tucked in the blouse of a buxom beauty.

Suleman paints India at its awkward best. What looks funny at first look with silly characters and subjects, trivial perhaps, but just around the corner of your half-smile, you realize, how she hits with her vivid details of a world which memory refuses to forget but the mind does not bother to remember. These are pictures of gawky characters in loud, gaudy clothing- taking the viewer back to the mofussil life of melas, mohallas and qasbas. Her paintings, with their innate humour, bump into your own nostalgia in a very narrow alley of the lives gone by.

She captures the functionality of life in its mesmerising, witty, funny colourful shades; the left-over of a wannabe world flashing by. Her works tickle, amuse and amaze.

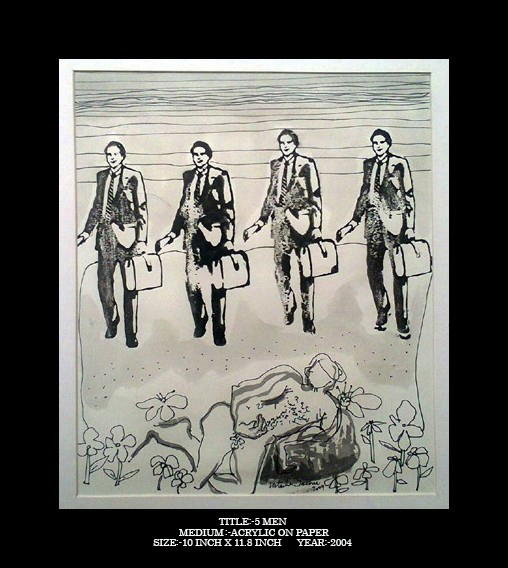

While Mithu Sen’s dark humour presents itself in subversive collages and pokes fun at the morality of a repressed society; expressed in her series of works exploring the crises and anxieties of the sexuality of the Indian male, like in Black Candy, Nitasha Jaini, a Gurgaon based artist, mocks the prototype urban male, for his lack of originality and imagination. Like an industrial product, falling out of the conveyor belt; the office-going man in slick clothing, expensive bags, shades and imported shoes; the entire ‘personality’ of pretence, greed, power and dominance becomes laughable for its pretentiousness. He represents the life between “red traffic lights“, one of the titles of her works.

Through her prototype male, she unfolds a persona that defies the façade of the macho — the subjugated man of social norms and imposed ambitions is, in fact, a compromised figure. Nitasha not only paints the man, but she also re-creates his predictable world, at times dream-like with tall buildings rising in the background, cars moving all around, or, hanging from a tree, like a man’s desired fruits. She explores the hidden, stubborn child behind this prototype; the victim of an image. The efforts of this prototype to stay put into this image amuse and sadden; in a Chaplinesque manner.

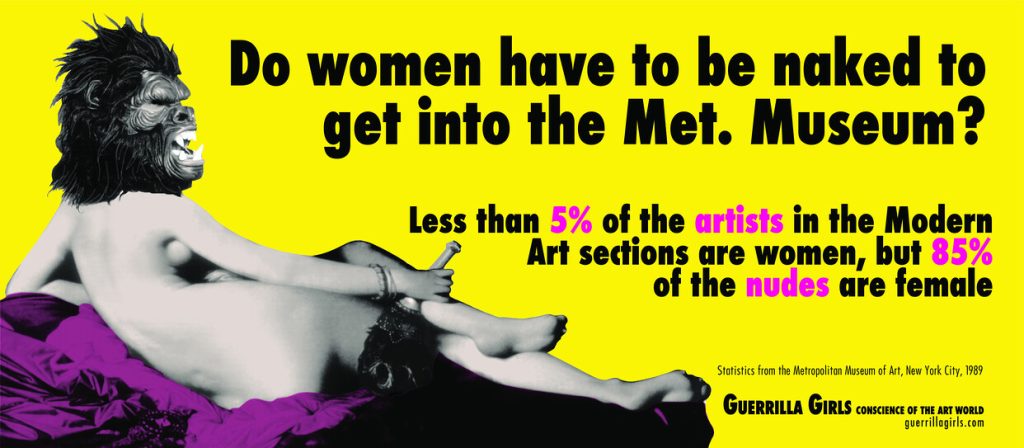

Guerrilla Girls, a group of anonymous feminists who fight sexism within the art world, found, while over 90 per cent artworks shown at MOMA celebrate female form (sans her other attributes) only two per cent of female artists are given the space to showcase their works in the prestigious museum. Nitasha paints only men, as a subversive act.

Tarun Jung Rawat lets his verbal skills tickle and dances around the visual space. With such chuckling titles to his works as, ‘Dancing Kree-Kree Flying Time’, ‘Tales, Tails and Tricky T Trails’, ‘Prey Seeker Deceiver’, ‘No Never Don’t Yes Can and Will’ and ‘Don’t Bleed the Freaks’, you know the artist has not forayed into visual space from lexical handicap. His quirky creative space is a continual extension of mediums and ideas. His own struggles to strike a chord with the viewers of diverse classes create an amusing landscape of kinetic ideas.

Texting the laugh-lines

Speech blurbs, thought bubbles and the nuances of graphic illustration enter the canvas to express the absurdity and the hybrid reality of the times we live in.

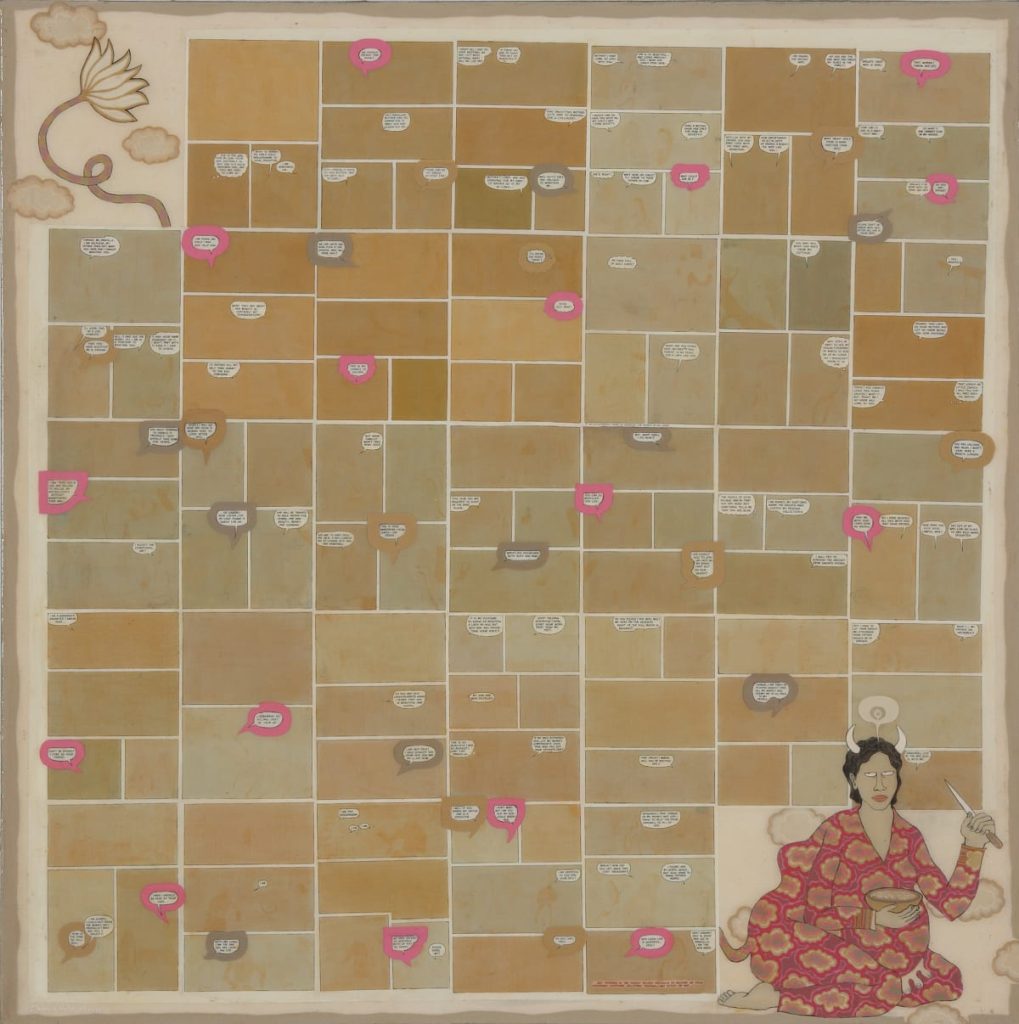

Dhruvi Acharya introduces speech blurbs while she plays on comic values by juxtaposing narratives of reality and fantasy, alongside a dark vision of contemporary urban life. This enables her to impose the serious with the humorous. She casts a wry glance at urban society in her works, interpreting it with barbed humour.

The macabre tales she offers are often extrapolated from her personal life. As a consequence of increasing pollution, there is a shortage of breathable air, in a series of her works titled One Life on Earth. To survive such a post-apocalyptic world, she envisions all female inhabitants carrying ‘breath packs’–personal respirators– on the backs; sprouting flowers on their heads to breathe while the lower bodies of the mutants, who survived this crisis, are shown to have become like water bags—to keep the personal life-giving plants alive.

Amusingly, in this grim scenario, the weapons of defence, for the females, are none other than emblems of fashion and sophistication of the urban woman. Well-manicured nails painted a flamboyant red become claws and chic suede boots are made lethal with spikes embedded in their soles.

She goes beyond cultural critique; creating a counter-cultural narrative. Dhruvi questions the cliches and stereotypes pushed by widely read Indian comics like Amar Chitra Katha. She paints complete frames over the ideal woman, of the women who define their self-worth as they choose. With sexually subversive speech bubbles, she leads the viewer to a logical outgrowth of the age-old, accepted iconography of the ideal Indian woman and places below the painted grid of speech blurbs, an overweight woman – utterly incongruent with the image provided by the folktale – lying on her stomach, perhaps surfing the internet on her Apple Mac notebook.

Like Tarun Jung Rawat, she too makes use of sounds—of onomatopoeic words to express violence on the canvas. Her works titled Wham! Kerplonk! Splat! Bam! and Mumbai 11/7 engages with terrorism and its infiltration with weapons of mass destruction juxtaposed with machetes and knives and pistols. Her works skilfully adapt the visual dynamism typical to comic book illustration as she lampoons the urban patterns of living and, consumerism.

Mithu Sen also uses text in her works, but her use of it is altered to complement a very different visual aesthetic of anatomical, anti-aesthetic forms or kitschy collages of images, picked from popular culture.

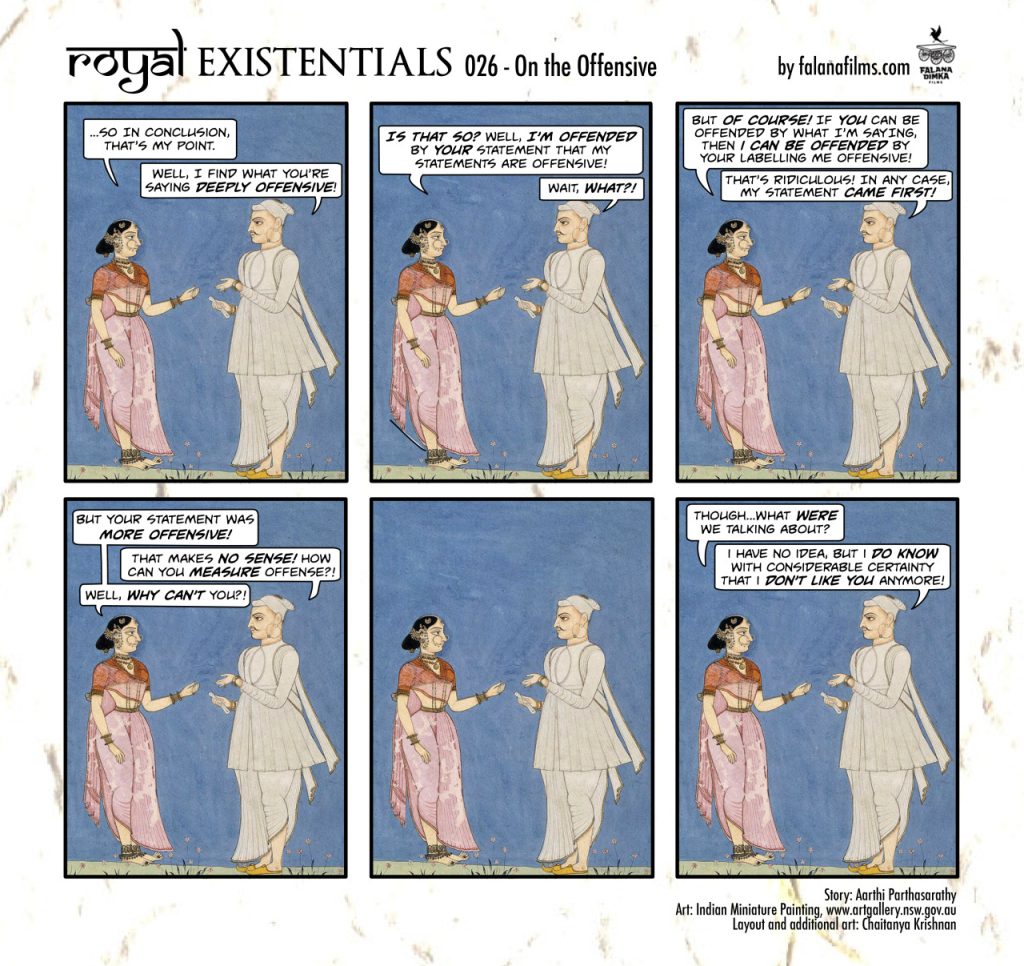

In a webcomic series, Bangalore-based artist Aarthi Parthasarthy narrates the ironic tales of unfairness titled Royal Existentials, in miniature style. The miniature art provided a window into the lives of the kings and queens; they never had an opportunity to speak for themselves. Aarthi uses multitudes of characters in opulent settings; breaking their enigmatic silence with her tongue-in-cheek take on inequality; filling the speech bubbles with jokes and punchlines.

Graphic novelists provide humorous reading and matching visuals of situations and landscapes that could otherwise be rendered prosaic. In India ‘sequential art’ is not alien but its manifestation has not gone beyond mythological panel art. With no prescribed styles, graphic novelists, nascent as they are, experiment with different styles; from political caricature to zany punk to rough pencil sketches. They are using the skill to provide glimpses of the everyday identity crises and quirks of less-than-extraordinary characters and contexts.

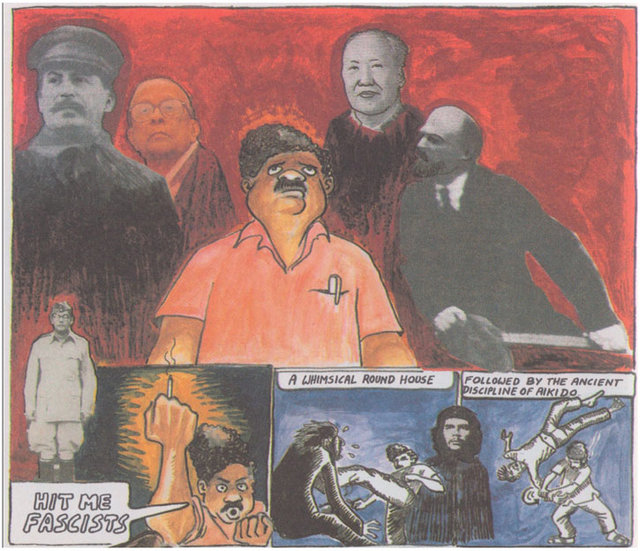

Sarnath Banerjee uses his background as a graphic novelist to present the universes of ordinary people in a narrative that encourages humorous reading of characters, with an emphasis on form and its particularities. Banerjee also instruments caricatured forms and panel sequences to set the proscenium for humour and follows the aesthetic that one is used to in comics.

The success of humourous content in the graphic novels comes from its simple, fallible characters and their ordinariness, which the reader identifies with. Banerjee’s first novel Corridor followed the lives of three ordinary men who whiled away their time in a second-hand Delhi bookstore. It had roadside hustlers and garish billboards, of liberated college students and their conservative landlords, of trendy parties and shady markets.

Banerjee made his characters straddle east and west, culture and kitsch, high and low—to make Baudrillard wash himself with the local Liril soap.

Another novel of his The Harappan Files is an encyclopaedic collection of illustrated micro-stories featuring middle-class Indian characters. It unfolds in a careful sequence of lush, atmospheric watercolours. Graphic novelists like Banerjee, Vishwajyoti Ghosh and others have popularised humour that mirrors the ordinariness of life with quirks.

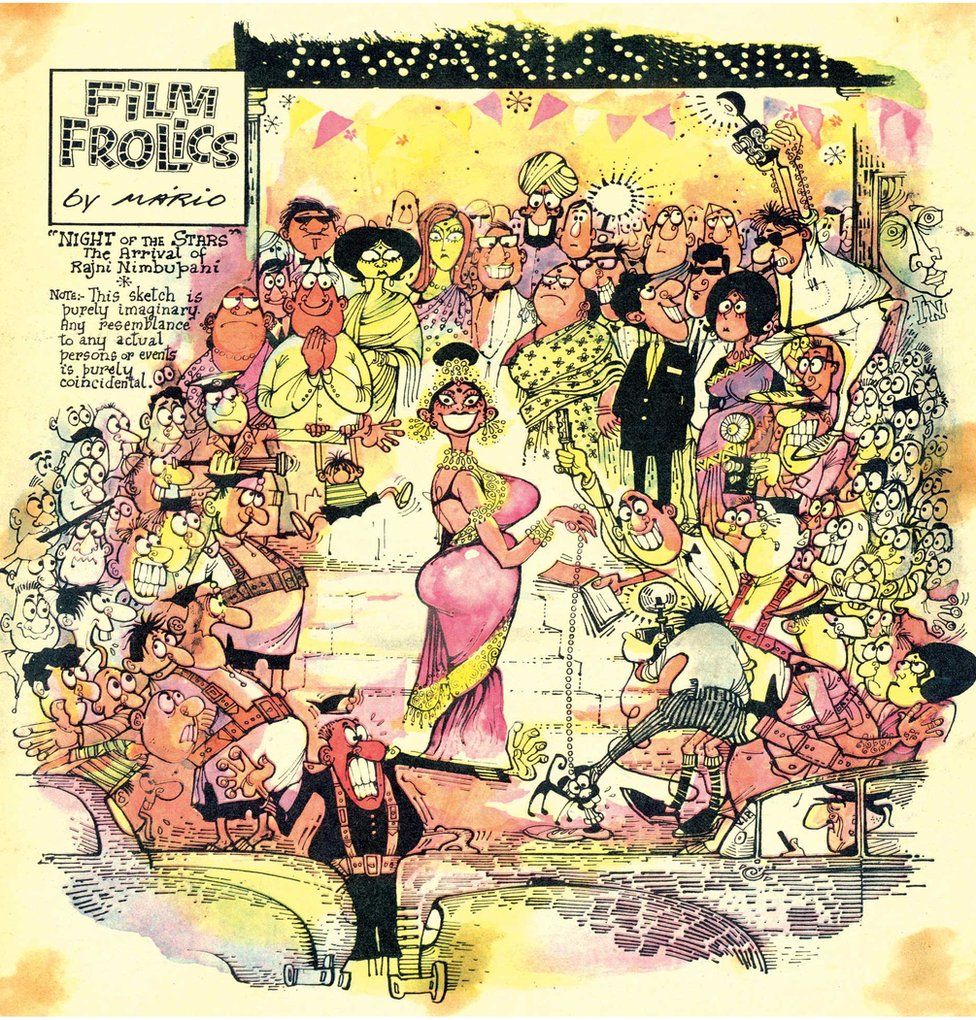

Mario Miranda’s fine pieces of art, depicting life as he had seen and observed, in Bombay (now Mumbai) Goa and other parts of the world, took cartoon illustration to the next level. The seemingly simple lines of his characters that brought a smile to people’s faces, with his unique worldview, were humorously artistic. The memorable characters of Miss Fonseca, the minister Bundaldass, Bollywood star Rajani Nimbupani, canines and their families and many more were animated by his witty observations. He spoke through his characters; even buildings spoke with the character he lent them. The relatability of characters and situations that people encounter in their day-to-day lives, gave his art unprecedented popularity.

Humour discovers diverse genres. Exaggeration, juxtaposition, and mirroring; techniques artists use to evoke humour, and highlight, what remains seemingly muted in a visual language of social critique. This is done in light-hearted contexts. These works are presented without any embellishments.

Contemporary artists engage in a critique of the capitalist, global society from a local vantage point, incorporating confused visual, moral and private universes.

The humour, in the works of several women artists, comes from conflicting cultural landscapes they find themselves straddled in. Their works incorporate satire, parody, irony and cynicism; which is also significant to the internal logic of these works.

The purpose is not only to evoke a chuckle; it is a serious matter. As life becomes complex and contradictory, does humour become subtler and barbed? Or, it gets a sharp, acidic edge. It depends on the sensitivities of the viewer.