Krispin Joseph PX

Toxicity is a TKM Warehouse installation in Kochi Muziris Biennale, an invitation program that fetches numerous things together to an Indian audience. We must keep the show in mind as some places in India are toxic because of illegal mining and multinational companies exploiting our natural resources with the help of our corrupted political-state system.

Nowadays, green energy and a sustainable lifestyle are the fuel at the discussion table in a time of global warming. We all need mobile phones, electric cars and other technology to manage our lifestyle to be “cool and “green”. But there is one thing we need to address; this technology needs some natural resources, like Lithium. One of the poorest countries in the world, Congo is the leading supplier of Lithium (60%) in the world. Some African countries suffer from the world’s need for “green energy and rechargeable batteries for cell phones, cars and other technology that make life smooth.

I am still determining where I can start to write about the “unknown” subject of Congolese lithium mines and the exploitation of the natural resource of one of the poorest countries in the world for green energy. I read some articles and other materials to understand these issues more closely. Nicolas Niarchos writes an essay, The Dark side of Congo’s Cobalt Rush,” in the New Yorker, and Michael Davie’s Blood cobalt reminds me of Blood Diamond.

The title of Toxicity comes from “Toxic” and “City”. The city becomes toxic for the people who live there, and there is a reason for this Toxicity. I am not too surprised to confront “Toxicity” because, more or less, these stories are like my stories, my landscape and my naturally resourced country, or we are waiting for this one to happen to us. Wherever natural resources are available, this Toxicity should emerge in some form. The problem that Congo people have been facing is the presence of natural resources that the world eagerly wants to make Lithium batteries for various purposes.

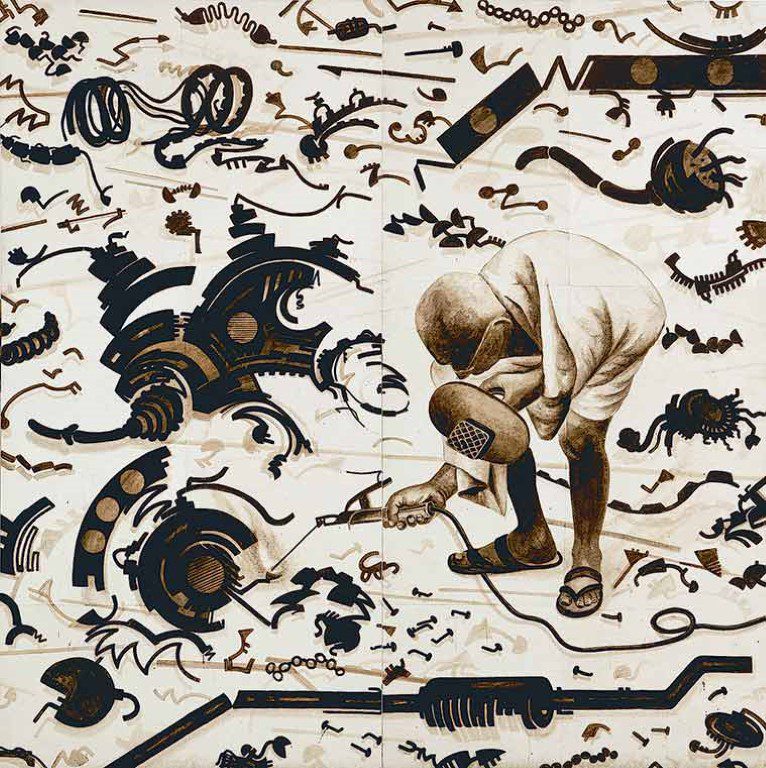

This project has many layers; a significant one is an animation, “Machini”, directed by Tétshim and Frank Mukunday, that won many international awards for the outstanding narration of the existing problem of Cobalt mining in Congo. This ten-minute stop-motion narrates the story of a town at the foot of a mining industry; the inhabitants’ daily life is upside down because of the world’s growing need for lithium batteries for a better future for the people. They dig for Cobalt everywhere, including their home.

Animation director, Tetshim’s family have been living in the neighbourhood of an acid-eaten location. Franck Mukunday grew up near the waste disposal of Gécamines, the company administering the mines since the colonial era. In this animation, directors reveal the secrets of inhumane practices in “artisanal” cobalt mines, including child employment. Cobalt mining causes pollution in Congo’s air and water, bringing congenital disabilities and deplorable living conditions affecting millions of people. The film narrates the terrible story of a Congolese town where Cobalt and Lithium are extracted for the engines of our pretty electric cars that may carry us with our children and dear ones with music and calmness through the busy city.

Toxicity is a human-made condition that more or less affects every corner of the world, their social lives and their existence. The project is a stem of Lubumbashi Biennale and reaches Kochi Muziris Biennale with a visual impact of the postcolonial urban settings that creates a space for discourse. A natural resource like Lithium is a Damocles sword for Congolese people that brings them fate and shapes their industry, economy, ecology and culture. This project raised ethical questions in the contemporary social world; how can we create a greener life with material brought to us from another part of the world that brings more harm to them?

The people from Congo start digging for Lithium in their homes because the world needs it more and more than ever. They dig for us; they dig to satisfy our desire and need. The exhibition’s backdrop told us about the fatal connections between the world economy and the lithium and cobalt reserve in Congo.

Bicycle with batteries is another layer of this installation that brings the layer of social realities in Congo. Two bicycles and used batteries with looped voice calling for the sale of used batteries. That voice call is haunting the exhibition hall because that voice call is haunting Congolese people’s imaginations with toxic and diseased landscapes. That layer independently narrates Congolese life’s invisible recyclers, characterised by a used car battery seller.

The element of Lithium comes back to Congo as used car batteries that bring a dream for someone trying to make a livelihood from selling. It is a never-ending story of a wretched world parallel to the world’s urbanised and metropolitan settings.

Did Lithium mining bring money and good life to Congo? The answer is no. Ordinary people are only labourers from beginning to end. A sign of this is fixed on the wall as a piece of cloth with an inscription: Journée International du Travail – Vive le 1er Mai, translated to English as ‘The International Labor Day – Let’s celebrate the 1st of May’. This cloth is a traditional fabric that women use for wrapping around the waist that carries a message, political or other.

Another layer is a 16mm archive footage based on a fictional work\research entitled UBATIZO, which tells of a dangerous disease set in motion by the same toxic mining. Some visual elements bring the Toxicity into motion: the woman fetching toxic water from the well, the Family father with toxic water, Maman in the garden at the source of toxic water, Dr Mayeye demonstrating the challenging walk of a patient, and patients moving in their enclosure during recreation. These visuals tell the dangerous elements and effects of Lithium mining after the impact of toxic components.

Finally, mining creates artificial lakes in Congo with muddy water. Congolean photographer Georges Senga’s ariel photographs tell about industrial ruins, artificial lakes and neglected neighbourhoods. How the lithium mines changed the fate of a country forever is a horrible visual narration that Toxicity brings all together.

This installation takes us to an unknown area of resistance and decay from beginning to end. A collective body of different mediums works together in an individual capacity that brings issues precisely to our eyes. The Cycle, the animation, the photographs, the fabric, the archival footage and the sound create a sensory experience that makes us more aware of natural resources and our life.

Krispin Joseph PX, a poet and journalist, completed an MFA in art history and visual studies at the University of Hyderabad and an MA in sociology and cultural anthropology from the Central European University, Vienna.