Early Life and Background

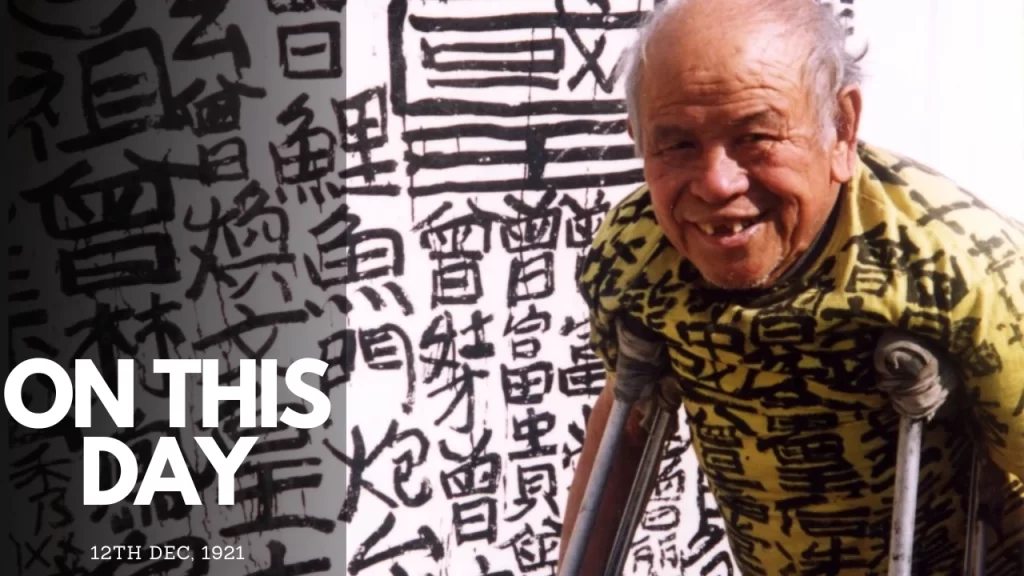

Tsang Tsou Choi is widely known as the “King of Kowloon.” He was born on 12th Dec, 1921 in a small village in Liantang, Guangdong Province, China. He would later migrate to Hong Kong, where he lived the rest of his life and became a cultural giant. Tsang had humble, unexceptional beginnings but left an indelible mark on the Hong Kong art scene. Such deprivation was the breeding ground for his early years, along with very harsh conditions and a sequence of events that would later become one part of his obsessive life long motivation to get back what he considered was rightfully his land. He was one of the millions that fled rural China seeking opportunity in Hong Kong, which he did in 1937. At the time, however, Hong Kong was still a British colony in what is known as the International period and this would have a huge impact on Tsang’s identity and eventually his work. The city he explored embodied a unique blend between firmly implanted Cantonese local customs with that of the British colonial presence. This tension defined Tsang’s perspective and created the context for his distinctive voice.

Where the King of Kowloon Came From

Tsang made an amazing find back in the 1950s, when going through archives of his family history he found records that suggested ancestors of his had once ruled a significant portion of the Kowloon Peninsula. It was this realisation that sowed the seeds of his own self-appointed label as “the King of Kowloon.” Tsang craved the belief that he had inherited this land from his ancestors, and so grew obsessed with taking back Kowloon for his own. He was absolutely sure he was the true king, and decided to claim his “ownership” where it is most apparent—by means of graffiti.

Style and Technique of Calligraphy

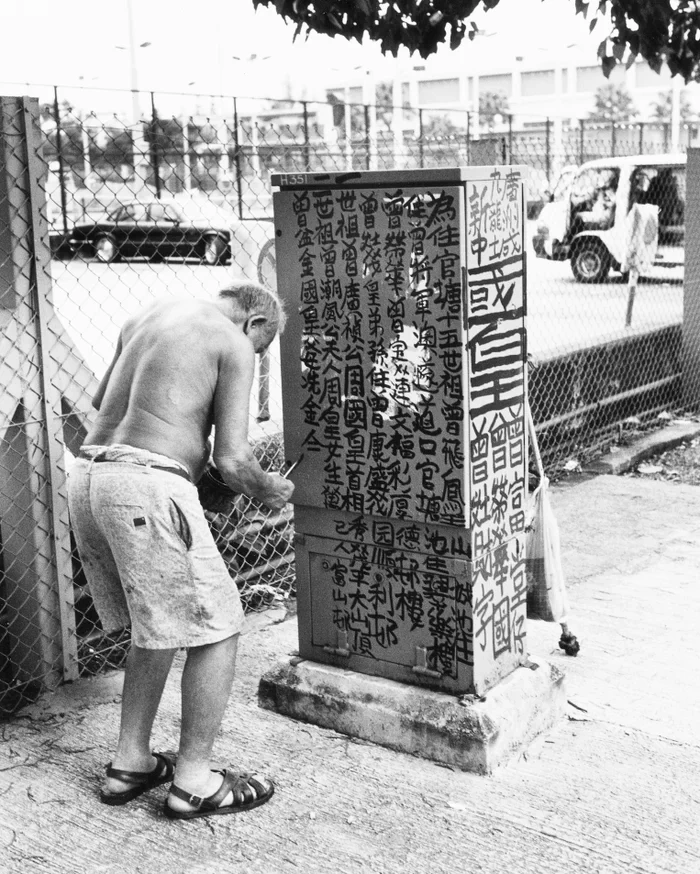

Tsang’s graffiti which has a distinctive Chinese calligraphy style is named “rough” and unpolished by many critics yet conveys a sense of intimacy with a high emotional load. Armed with ink or black paint, Tsang filled up public spaces with big, bold freestyle strokes to create a work of art as he transformed walls, electrical boxes and lampposts into his canvas. His writings usually consisted of a combination of descriptions of his ancestry, territorial claims and complaints against British colonialism. The messages were elaborate family trees, maps and the names of Chinese dynasties interspersed with his cries against what he thought the authorities had done to his family.

Although Tsang’s method was casual and rarely resembled the finishing touches of classical calligraphy, his pieces felt like unavoidable manifestations. With a flat brush or marker he wrote in very large, sprawling letters filling any available space. The graff was his graffiti, and the writers were crews to him. Over the years, by sheer persistence and force of volume, Tsang made his obsession into a signature visual dialect—a combination of text with symbol and statement that together served as an almost legendary testament to his ownership claim on Kowloon.

Social and Political Context

Much of Tsang’s work, however, cannot be understood without specific reference to the socio-political landscape of Hong Kong in the second half of the 20th century. His graffiti appeared at the juncture of fast local urbanisation, political cracking up and identity crisis in Hong Kong. The colonial rule was always in conflict with the local identity as the city burgeoned into a vibrant cosmopolitan. The decidedly anti-colonial themes of Tsang’s graffiti, as well as his claim that the land was part of his “ancestral” land, aligned with a population struggling to define its own sense of self under British rule.

Tsang was derided by some as a madman and hailed by others as a folk hero representing the collective struggle of Hong Kong citizens. It served both as protest art and reflection of the rebellious spirit of resistance towards colonial authority. His stake of Kowloon was both personal and political, wanting to share the ache of being marginalized, a voice crying out for validation and autonomy through his art. A few highbrow examples were outsider art in the truest sense of the phrase, and Tsang’s work was one of them — nobody expects us to be mythic gods, embodied as belief splattered on streets at night; none expect our lives to have anything personal about it, but only collective, empty from intrusions of the political.

Recognition and Legacy

Tsang Tsou Choi became an unlikely icon (with or without his formal training stamp) of Hong Kong contemporary art. During the 1990s, art curators, scholars and finally the public began to take note of his graffiti. His work was praised for its untamed energy, perceived as a down-to-earth embodiment of local culture and identity opposed to the refined aesthetics typical of the high art. He has received formal recognition for his art; in 2003, the Hong Kong Arts Centre held an exhibition featuring Tsang’s work. The moment was bittersweet for a man who had spent decades on the fringes, sneaking his graffiti style into the every day in glorious anonymity. From graffiti on the streets, to prestigious exhibitions — like many of Tsang’s works featured at the Venice Biennale.

His graffiti persisted, and while his fame snowballed, Tsang viewed himself less as an artist than a king with a claim to the land. The thematic concerns of his later works also began to show a growing influence on nostalgia, loss and the feeling of a time gone by—examined through the lens of the ever-shifting Hong Kong urban landscape. The paintings of Tsang turned into a visual catalogue of the changing city where history, memory and yearning, both the artist’s and her home, intermingled.

Impact on Cultural and Artistic World of Hong Kong

The impact of Tsang Tsou Choi on art and culture cannot be exaggerated in Hong Kong. Three decades ago, he paved the way for generations of artists to come to Hong Kong as one of the earliest street artists here — instilling a sense of rebelliousness and an approach to urban public art that fruitfully blurred lines between painting, sculpture and form. Today, Tsang is regarded as a trailblazer; his work embodies and hones in on the spirit of Hong Kong — the coexistence of tradition and modernity, East and West.

Referenced in many exhibitions, films and publications, his work remains a constant point of reference for the complexity of Hong Kong as an artistic legacy. Since his death in 2007, however, Tsang’s work has been re-assessed more as social commentary and protest art than graffiti. He remains a source of inspiration for many artists and activists who see in his story an archetype of empowerment, defiance, and search for identity at a time of intense social upheaval.

Death and the cultural icon

In Hong Kong, Tsang Tsou Choi has attained an almost mythical status in the years since his death. Although most of his early graffiti has been lost to urban development, the story remains. His remaining works exist only in museums and private collections, while his impact stretches out beyond the realm of art into popular culture: remembered as an embodiment of Hong Kong’s troubled identity and history. His most iconic works are housed in the Hong Kong Heritage Museum, where they remain to spark inspiration and contemplation. There have been books, documentaries and academic studies about Tsang’s life — the man behind the art. The makeshift art of the King of Kowloon lives on, a symbol often in defiance of the authorities of Hong Kong’s spirit fame. His influence is not solely a remnant of his oeuvre or even his actual art, but rather the belief that one deserves to be who they are and the courage to earn it unapologetically against all that may oppose.

Above all, Tsang Tsou Choi was not just a street artist. He was a storyteller, a rebel and a visionary whose life and art reflect the heart and soul of Hong Kong. A story that reflects adaptability, ingenuity and a bond with place and culture. Case in point, Tsang was an artist who created his art using graffiti exploring the city that he fell in love with but also as a contemporary artist the issue of freedom to the world of contemporary art.

Contributor