Saptarshi Ghosh

Judy Chicago and Shirin Neshat are two very different artists, but what links them is the struggles they had to face as women in the male-dominated American art world. That being said, their individual struggles were very different owing to their different backgrounds. Born in the city of Chicago in the late 1930s, Judy Chicago is a doyen in the realm of feminist art, known for her confrontational works, comprising installations, painting and sculpture. Being a woman in the male-dominated art world, she had to negotiate several impediments in her art career. Also a fierce feminist, she participated in many women’s movements while attacking male chauvinism and patriarchy through her art.

Courtesy: Aware Magazine

Neshat on the other hand spent her childhood in Iran before travelling to the US for higher education. Now she is an American citizen, based out of New York City. Neshat’s struggles in her initial days were very different from Chicago’s, who was after all a white woman enjoying significant privilege. Being an outsider in the US, Neshat had to grapple with an alien culture and struggle to fit in. She could not make it in the art industry initially since she could not discover her artistic voice. Yet, in the end, she did find it, and went on to become one of the most important artists working currently.

Courtesy: Circa.art

Despite their different locations along the axes of social privilege, Chicago and Neshat managed to overcome their personal challenges and make their mark. This International Women’s Day, let’s celebrate their resilience and achievements!

Judy Chicago

Born in 1939 in Illinois, US, the trailblazing Judy Chicago was among the first generation of feminist artists, who introduced a feminist consciousness in the American art scene of the 1970s and ‘80s. Christened Judith Cohen by her parents, she changed her name to Judy Chicago in 1970, taking the name of the city of her birth, in an attempt to fashion a new identity – one not imposed on her by the patriarchal society.

In her recent autobiography The Flowering: The Autobiography of Judy Chicago (2021), she recounts her struggles as a young woman artist in the 1960s. She writes, “Being a woman and an artist spelled only one thing: pain.” Even in grad school, Chicago would experience the disapproval of her male professors when she created a series of abstract works painted on car hoods, featuring collapsed male and female genitalia.

Her experimentations with minimalism at that time was an attempt to fit in and be like the male artists of those times. To be deemed an equal, Chicago even tried to emulate the lifestyle of men: she wore heavy boots, smoked cigars, drank with the boys. However, deep down, she hated it. Chicago witnessed her male contemporaries flourish even when her own career prospects would get thwarted. “Eventually, I got tired of trying to be a guy!”

Courtesy: Dazed

Chicago was also a feminist art educator responsible for creating safe spaces for women artists, where they could explore their potential and not get pushed aside by their male counterparts. In 1970, she was invited to teach a course on feminist art exclusively for women at what is now the California State University, Fresno. This was later redeveloped with artist Miriam Schapiro as the Feminist Art Program at CalArts in 1971. Chicago did not impart formal art education; instead, she instilled feminist consciousness and sought to empower the young women. Skills like knitting and embroidery, usually associated with women, would be brought in and incorporated with their art practice. In 1972, Chicago, Schapiro and other women artists set up Womanhouse in a Los Angeles house, where women could collaborate and make art. These shared spaces for artistic collaboration set up networks of solidarity among women.

Courtesy: Frieze

Evidently, Chicago’s art practice too is informed by feminist ideologies. Her greatest work is The Dinner Party (1974-79), an epic installation comprising a triangular table with 39 place settings. Each of these place settings commemorates a historical or mythical woman, such as Sappho, Artemisia Gentileschi and Georgia O’Keefe among others. Conceptualised as a ceremonial banquet, the work took five years to complete and saw the participation of more than 400 volunteers, mostly women. Chicago wanted to unearth the contribution of women which, most often, gets omitted from memory and written accounts.

Even at the age of 83, Chicago retains the strong commitment to her ideals and passion. This International Women’s Day, we at Abir Pothi celebrate her illustrious legacy and hope that she continues to provoke us with her art!

Shirin Neshat

Born and raised in the Iranian town of Qazvin, Shirin Neshat’s exposure to art during childhood was very minimal. It was literature that she was deeply invested in. Belonging to a progressive family, Neshat was encouraged by her father to explore the world and find her own footing. She left for the US in 1975 to study at the University of California, Berkeley, thereby escaping the societal and political upheaval brought about by the Iranian Revolution in 1979.

Neshat occupies the position of an artist in exile – one who is an outsider both in the West and her homeland. She struggled to adjust to her new life in the US. At university, she experienced difficulty in reconciling her Persian heritage with the Western art being taught. Moreover, her university education altered her outlook towards being an artist: “At UC Berkeley, I was totally lost. I immediately realised that my idea of art and being an artist was stupidly romantic,” she says. “[Y]ou have to have ideas that are more than intuitive. You have to know what you have to say.”

Her situation worsened after the Iranian Revolution. “Horrific things were going on in my life – I lost my immigration status, couldn’t go home anymore, and was separated from my family,” she recalls of those times. “My studies took a backseat. I wasn’t blossoming like some of the other students.” She began to doubt her abilities.

After graduating from UC Berkeley in 1983, Neshat shifted to New York City. There her work was rejected for not being up to the mark. Neshat soon got intimidated by the New York art scene and eventually decided to give up art, thinking it was not her cup of tea. Instead, she worked for a decade at the Storefront for Art and Architecture, a cultural organisation, as a co-director with her ex-husband, who founded it. During this time, Neshat interacted with eminent artists like Vito Acconci, Mel Chin, Kiki Smith, which greatly enriched her. She asserts, “My true art education came from Storefront.”

Courtesy: Gladstone Gallery

In 1990, Neshat returned to Iran for the first time after the Revolution and was shocked by the radical change underwent by her country. After returning, Neshat felt the impulse to create art in order to keep “this relationship alive again between [her] and Iran”. Her earliest works were the photography projects Unveiling (1993) and Women of Allah (1993-97), exploring the intersection between femininity and Islamic fundamentalism in Iran.

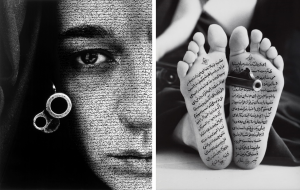

Her work deploys a female gaze and examines the lives and bodies of women living under oppressive regimes. In the Women of Allah series, Neshat overlays photographs of women – both self-portraits and portraits – with written text from Farsi poems by Forough Forrokhzad, a celebrated Iranian feminist poet. Much of Neshat’s work also examines the physical, cultural and psychological implications of wearing the chador or veil, made mandatory for women in Iran following the Revolution. Neshat is also an accomplished video artist known for works such as Turbulent (1998), Rapture (1999) and Soliloquy (1999). She even won the Golden Lion for Turbulent at the Venice Biennale in 1999.

Shirin Neshat’s journey teaches us the importance of discovering one’s identity and voice as an artist. You may not always find it immediately, which is perfectly fine. If Neshat had not given herself the time and space to grow, she would not have been able to find it: “I’m very glad I left art when I did. There’s nothing worse than mediocrity. Many of us go to school, and we’re content even if the work isn’t great. I needed to find what I had to say, what people should pay attention to. […] I figured this out after my experience in Iran.”

This International Women’s Day, we at Abir Pothi celebrate both the struggles and achievements of Shirin Neshat!

Bibliography

- https://elephant.art/thats-the-chicago-way-the-uncompromising-life-of-judy-chicago-19092021/

- https://www.apollo-magazine.com/you-have-to-choose-hope-an-interview-with-judy-chicago/

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Judy_Chicago

- https://www.google.com/amp/s/www.artnews.com/feature/who-is-judy-chicago-why-is-she-important-1234602444/amp/

- https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-shirin-neshat-path-art-school-outcast-contemporary-art-icon

- https://nmwa.org/art/artists/shirin-neshat/

- https://magazine.artland.com/shirin-neshat-land-of-dreams/