Digvijay Nikam

A question that often surprises spectators of art is what motivates artists to get drawn towards certain subjects and images that later recur throughout their oeuvre. Why is M. F. Hussain enamoured by the horse? How is that different from Sunil Das’s fascination with the same beast? Similar is the case with another stalwart of the Indian art world, Tyeb Mehta – a painter, sculptor, and filmmaker, who was preoccupied with his own set of subjects throughout his outstanding career.

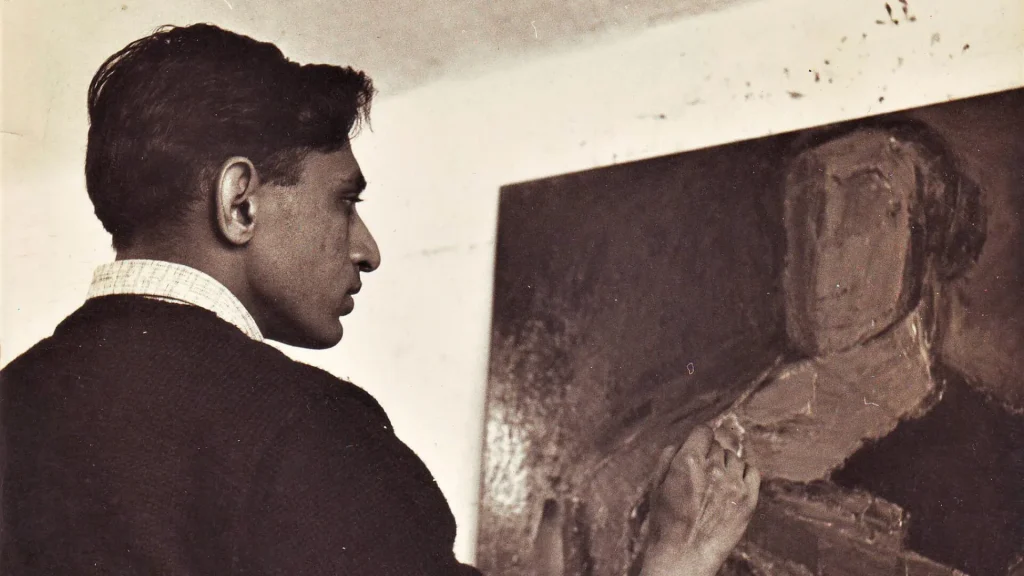

Mehta was born in 1925 in Kapadvanj, a town in the Kheda district of Gujarat in India. Brought up in the Crawford market neighbourhood of Mumbai, Mehta worked as a film editor in a cinema laboratory for a while before joining the Sir J. J. School of Art. He spent most of his life in Mumbai, except for three short stays in London, New York, and Shantiniketan, each of which had a distinct impact on his work. Mehta brought a revolution to the international auction scene with his works that fetched millions of dollars and triggered the subsequent Indian art boom. Even after his departure – he died on 2nd July 2009 following a heart attack – his paintings continue to attract viewers and buyers across the world. For instance, in March 2021, when Christie’s announced the Asian Art Week in New York, the artist’s Confidant, painted in 1962, shared space with many other significant masterpieces.

Santiniketan Triptych. 1986/87. Courtesy of Vadehra Art Gallery.

Santiniketan Triptych. 1986/87. Courtesy of Vadehra Art Gallery.

Mehta was part of the famous Bombay Progressive Artist’s Group which departed from the nationalist Bengal school and embraced Modernism with its post-impressionist colours, cubist forms and expressionistic styles. Speaking of his association with the artists of the group, he says: “…we learned and tried to understand paintings through each other. Gradually I realised that painting offered a world of expression, all its own. I forgot about films and became obsessed with learning what painting was all about.” Mehta’s earliest work is characterised by his interest in three motifs – the Trussed Bull, Rickshaw Puller, and the Falling Figure.

Trussed Bull (1961); oil on canvas. Courtesy of Vadehra Art Gallery.

Trussed Bull (1961); oil on canvas. Courtesy of Vadehra Art Gallery.

Tyeb’s first significant painting was that of a trussed bull executed in 1956. For him, the trussed bull is a symbol of great energy being blocked. When he encountered the bull in the slaughterhouse with its legs tied and thrown down before butchering it, he felt as if something vital was being lost, that it was an assault on life itself. The painting above from his early collection tries to capture this sense of uneasiness with the large figure of the bull lying on its back. In the early years of post-independent India, the bull seemed the apt representative of the national condition, the mass of humanity unable to channel or direct its tremendous energies. It was at the same time representative of his own feeling about his early life in a tightly-knit, almost oppressive Bohra community.

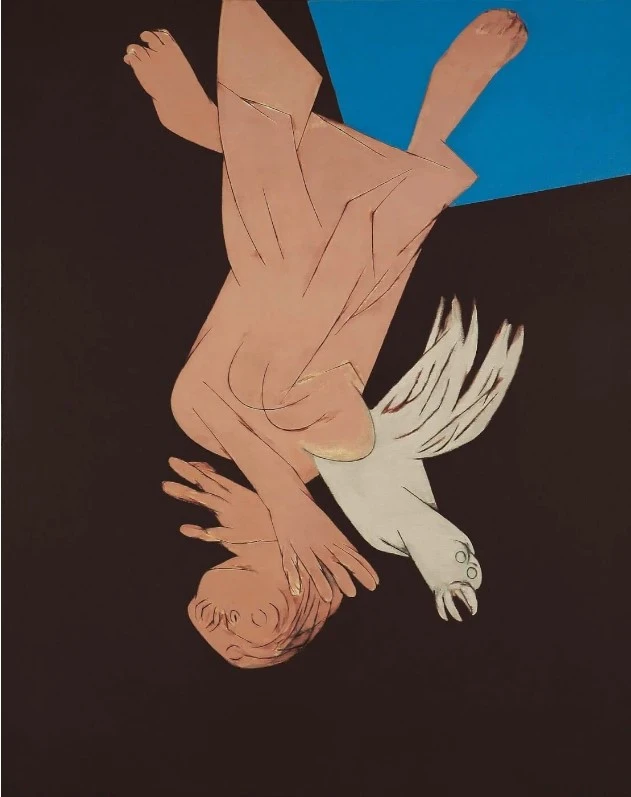

Falling Figure with Bird. Courtesy of Tallenge Store.

Falling Figure with Bird. Courtesy of Tallenge Store.

This strain of thought concerning unrealised potential continued to influence his other paintings especially the series titled Falling Figures. The falling figure was based on his experience of witnessing the violent death of a man in the street during the partition riots in India. The riots and Tyeb’s paintings question the legacy of independence. Were things going the way they should have gone? Is this what generations of people had fought for? All these paintings depict a man, sort of helplessly and abysmally gravitating downwards through space, possibly the sky, which is painted in different shades of strong colours in this series of paintings.

Eventually, Mehta added the figure of the falling bird which complicated the interpretations since a winged bird is supposed to fly. This gravity-defying emotive figurations were his attempts at communicating a sense of pathos and helpless suffering. Throughout his career, he kept returning to this figure. This particular work titled Falling Figure with Bird is one of Mehta’s most expensive since it was sold for Rs 9.6 crores by Christie’s in 2012. As one notices, Mehta’s personal anguish and the nation’s distress are incorporated into the painting in a rather oblique way which shows that his method to portray immediate social events was not illustrative like some of his other predecessors and contemporaries.

Diagonal, 1973. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of Mutual Art.

Diagonal, 1973. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of Mutual Art.

According to the art historian Yashodhara Dalmia, these paintings also mark the period which saw a radical transformation in Mehta’s works wherein he shifted from the harsh textures and expressionist imagery as seen in the earlier painting to minimal two-dimensional figures, stable use of colour, and deliberate experimentation with space. It was during this period of the 1970s that a diagonal element started to appear in his work. He says, “I was trying to work out a way to define space… to activate a canvas. If I divided it horizontally and vertically, I merely created a preponderance of smaller squares or rectangles. But if I cut the canvas with a diagonal, I immediately created a certain dislocation. I was able to distribute and divide a figure within the two created triangles and automatically disjoint and fragment it. Yet the diagonal maintained an almost centrifugal unity… in fact, it became a pictorial element in itself.”

Kali. 1997. Courtesy of Saffronart.

Kali. 1997. Courtesy of Saffronart.

In addition to these subjects, Mehta was renowned for his depictions of mythological figures, most importantly, Kali and Mahisasura. The 1980s were a difficult time for him, with Mehta having suffered a heart attack. The doctor had asked him to rest, but he decided to go to Santiniketan as an artist-in-residence. It was during his time at Santiniketan, he could feel the presence of Kali everywhere and ended up creating paintings of the deity. This monumental painting titled Kali created a buzz a few years ago when it fetched a whopping Rs 26 crore at Saffronart’s sale. The painting depicting Kali with a gouged mouth, distorted figuration, and minimalist use of colour along with the signature reconfiguration of space shocks the viewer; a shock that was a particular feature of Mehta’s paintings. And this minimalism was to define his later works in his career.

The appeal of Mehta’s paintings remains undiminished. Perhaps, it is the struggle for survival and the futility of existence that he depicts so beautifully in his canvases that touches a chord within all of us. His protagonists, whether they be ordinary men or mythological beings, have always tried to express very ‘real’ predicaments. His concerns are singular and universal at the same time and therefore, his art will continue to engage generations to come.

References

- art1st- Tyeb Mehta: Defining the power of the lone figure.

- Stir World-Early works of Tyeb Mehta and the birth of his key motifs…bull and falling figure.

- Stir World-A peep behind the lofty canvases of Tyeb Mehta to discover his towering personality

- Vadhera Art

- Saffron Art

- Tayed Mehta.com

Read More:

Tyeb Mehta: A modernist Indian master whose powerful paintings minted their worth

Contributor