Tyeb Mehta, one of the leading figures and prominent presence in Modern India Art, was initially associated with the Progressive Artist Groups and celebrated as a well-known Indian artist of his epoch. Tyeb Mehta (July 26, 1925 – July 2, 2009) was born in Kapadwanj, Gujarat, well known as a painter, sculptor and filmmaker. Tyeb was born into an elite-class family with a strong business connection with popular Hindi cinema. After finishing painting at Sir J J School of Art, he pursued a career in the movie world. He joined the Fazalbhoy Institute at St. Xavier’s College to study cinematography, but the second world war destroyed the film industry for a short period, and Tyeb started to get without practical film-making experience due to the lack of film stock.

The only way is to study theory without practicals. He joined the Famous Cine Laboratories instead; he worked there from 1945 to 1947 as an assistant to a film editor employed in creating documentaries for the Information Films of India series. From the film industry, Tyeb got a turn to Art, he acquaintanced himself with A A Majid in a tram, a famous art director in Bombay’s film industry, and encouraged him to join the art school and pursue Art. Tyeb set aside the film enthusiasm and joined Art school in 1947 and completed in 1952. The growing period of Tyeb Mehta and the others is a time of Indian independence and the sorrowful shadow of Partition.

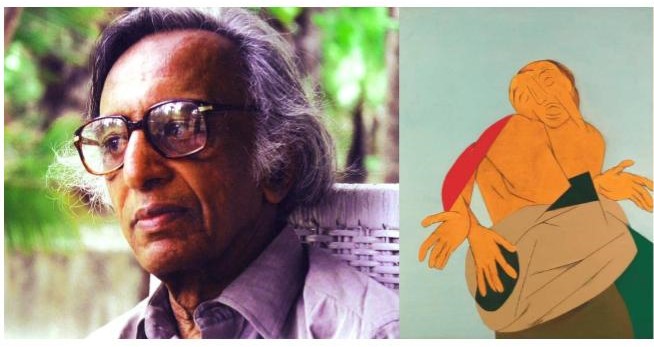

Courtesy: TOI

As an artist, Tyeb created a style of distorted aspects of human and non-human figures set amidst oblique bodies of colours and patterns. In his beginning phase of painting, human and animal figures are at a point of distortion; Girl in Love (1957), Kultura (1957), Head of a Horse (1959), Crucifixion (1959), Nude (1959), Untitled (Figure) (1959), Head (1957) are the examples of his painting of formless forms or shapeless shape. In this phase, the visual language of the Tyeb evolved through the influenced language of Francis Bacon and Barnett Newman’s artwork. Tyeb Mehta’s Famous Paintings celebrated those misshaping and diagonal elements; the subject is a falling body, Kali, or even the two people who met somewhere.

Tyeb Mehta’s Kali

Courtesy: Artnet

Tyeb Mehta’s Kali (1989) is leading newsrooms after fetching Rs 26.4 Crore in Saffronart’s Auction’, and the Indian art industry celebrates the legacy of the artists. In this painting, Tyeb Mehta depicts the Hindu Goddess Kali as having a gouged mouth and distorted shape. Tyeb Mehta brings Kali into his iconic style due to the boyhood recollections of violence and the haunting stories of Partition that bring so much misery to millions of people; as he experienced in his neighbourhood, violence against Muslims is common. That violence is validated in the name of God, then the artist questions the existence of God through his formless Art. “An artist comes to terms with certain images. He arrives at certain conventions by a reduction process,” Mehta once explained about his artistic practice.

Celebration Tyeb Mehta’s artwork starts from the Progressive Art movement, and the style he created is celebrated and honoured. Tyeb Mehta’s painting gives the figures much unpredictable performative language that builds in an Indian geographical and mythical location. Figures are gifted with expressive gestures like drumming hands or dancing feet; otherwise, embracing hands or extended fingers somewhere. Every performative element starts and ends inside the canvas, giving the audience more visual indulgence. The division of the animal and human body vanishes in Tyeb’s Artworks, and everything is coined with infinite harmony of shape and form.

In this Tyeb painting, religiosity is played as a strategy to address the primary contradiction in the formulation of modernism in India, as writes Karin Zitzewitz, and never be classified as strictly religious. In a detailed reading of Tyeb’s works, we can understand the pain of witnessing violence against Muslims after Partition. Tyeb’s Kali and other religious paintings create a questionable ambience of their violent motion.

Santiniketan Triptych

In his Santiniketan Triptych (1985), Tyeb uses the influential element of tribal life in Santiniketan and openly addresses the vibrancy of rural and tribal culture. The Santiniketan Triptych is monumental in Tyeb’s artistic practice because that works gives him an opening source of Hindu iconography. The festivals of the Santal community in Santiniketan and their celebration of life as a naturalistic movement, “the essential inspiration was the presence of a stout, short woman in white at the festival. She came and poured some water near the pole and then disappeared. I don’t know where. There was a shifting temple-like thing; it never occurred to me that she might be there. She seemed to disappear like a goddess, and then I found her sitting inside a hut, Tyeb said about this experience.

‘This woman, whom Mehta describes as a fleeting incarnation of the goddess, appears in the centre canvas, her split body painted in black, red, and white. Her two faces wear malevolent and serene expressions, and she is endowed with the multiple arms that signify divine power in Hindu visual culture and motion or conflict in Mehta’s body of work. The figure menaces a group of women seated with a goat. This central canvas is flanked by two others, in which an exuberant group of people—drummers or rope pullers—is juxtaposed with a figure falling through space, writes Karin Zitzewitz.

The diagonal method of dividing and distorting forms is a significant element of Tyeb’s work; as Karin mentioned, ‘introducing the diagonal into Mehta’s painting practice is a signal event in the artist’s biography, occurring just after his 1968 residency in New York’. ‘Mehta rejected abstraction as being too remote from his humanist concerns, so he began exploiting the tension between the colour field and figuration’, writes Karin.

Tyeb Mehta’ passed away in July 2009; after his death, he received Padma Bhushan as posthumous recognition. Tyeb Mehta was praised with this award in 2013, four years after dying. The Padma Bhushan is a testament to Tyeb Mehta’s gift to Indian Art; and a much-deserved honour for his work.

Tyeb Mehta : Distorting Canvas to Reconfiguring Space and Subjects

Krispin Joseph PX, a poet and journalist, completed an MFA in art history and visual studies at the University of Hyderabad.