Are you in a Love Relationship? Why are you in a relationship, and why are we expressing the Love and beauty of our relationship in Art and poetry? Why are we conserving our Love in Art? Art always plays as a lab for creating and experimenting with new things other than old tales.

Before Modern Art, the characteristic of Indian Art is an amalgamation of material and the spiritual in all creative initiatives and every aspect of life. Indian miniature paintings spread out in regions and styles celebrate ‘life, then ‘Love’ as their mundane and spiritual life. The book, ‘Kangra Paintings on Love (1962), written by M S. Randhawa and published by National Museum, New Delhi, elaborately discusses ‘Love and ‘Relationship’ in miniature paintings.

Introduction to Kangra Paintings

The Kangra School of Paintings is a born child of Kangra Valley, a former princely state, which patronized the Art, mainly under the leadership of Raja Govardhan Chand (1744-1773), a prince with a refined taste and a passion for paintings. Raja Govardhan Chand gives asylum to refugee artists trained in the Mughal style of miniature, and they start to live and paint the inspiring environment of the Punjab Himalayas.

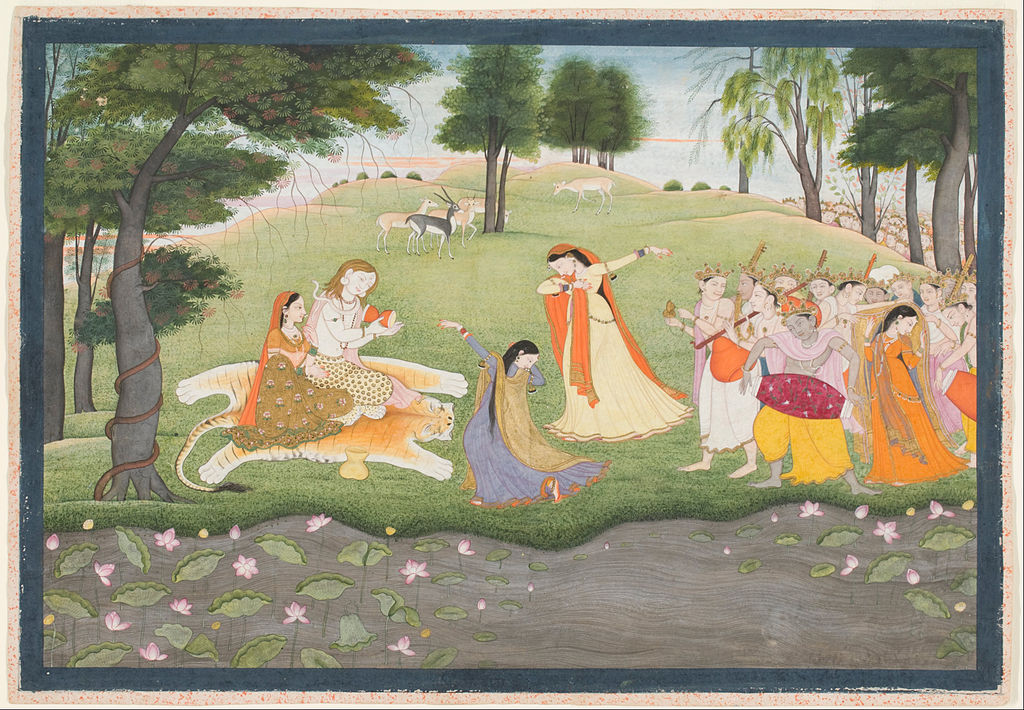

When the Mughal style met the beauty of the greeny valley with wave-like terraced paddy meadows and snowy upper part of the Himalayas with streams fed with the glacial waters, the Mughal style with its exposed naturalism flourished into the Kangra style. Why the Kangra miniature became prominent in the depiction of beauty, according to Randhawa, they didn’t paint flattering portraits of their masters and hunting scenes; the artists adopted themes from the love poetry of Jayadeva Bihari and Keshav Das, who wrote ecstatically of the Love of Radha and Krishna. Kangra miniature is so beautiful in the narration of Love because of the fantastic mixing of Mughal style, the poetry of Jayadeva and Keshav Das, and the new spirit of romantic love and bhakti mysticism.

Language of Love and Beauty

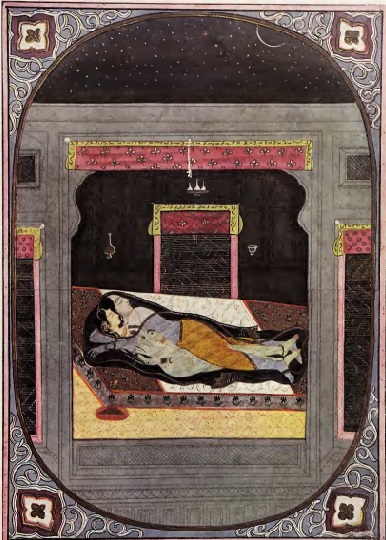

married life.26 The lovers are lying in close embrace, relaxed, satisfied and happy. The heroine’s face with its

expression of contented joy, her languor, and care-free abandonmentto the impulse oflove is symbolic of her maturity. She is the praudha, the experienced nayika, mature in her experience of love. | credit: Kangra Painting on Love

Art historian A.K. Coomaraswamy brought Kangra into Indian Art historical discourse after visiting Amritsar and Kangra and purchasing some paintings from a merchant. He wrote an essay on that style and depiction of the Kangra miniature. ‘Kangra’s painting glorified refinement, restraint, and divinity of beauty. Every Art is a language. What the words cannot express is sometimes conveyed in painting through space enclosed

in line and dabbed in colours. Kangra painting is an art both of line and colour. A vigorous rhythmical line is the basis of this Art, Randhawa writes.

Artists use rich colours to narrate the Radha and Krishna Love story and use pure blues, yellows, reds and greens to narrate these realistic yet poetic themes. According to scholars, they handle the painted canvas with care and the glowing beauty of colours, allowing them to fulfil the patronage’s desire.

‘These paintings are the visual record of a culture, the warm sensuous humanism of Vaishnavism, which found expression in poetry and ultimately in pictures of utmost delicacy and beauty. These paintings are fossils of culture, which, when studied and interpreted, tell us more about the historical past than the records of travellers or the dull cataloguing of facts by so-called historians and archivists, writes Randhawa, and she explains, ‘they mirror their age and humanity and the ideals which inspired them. Vaishnavism, which kindled the creative enthusiasm of the period, preached the religion of Love.

Apart from other regions and times, Kangra Artists focus on painting Love, a passionate, intimate, and ecstatic emotion of human life, and they reach the joyous aesthetic harmony of natural feelings. They use Krishna and Radha to narrate the human’s eternal theme of Love and intimacy and display their true and ideal Love. Kangra artists pass those feelings and natural beauty of ‘Love’ to us to understand the theme and treatment of that theme in a period that we were completely oblivious of in the past.

Kangra-style paintings, the artists from the Mughal court, focused on depicting women in their beautiful attire and ambience. They didn’t take any women as a model but narrated the women’s life and their adorning presence in the Kangra Valley and Palace. According to Randhawa, the artists distilled the essence of female beauty in these paintings, and they ‘formulate female beauty which we see in these paintings represent a vision realized through the contemplation of a thousand beauties’.

Love In Poetry and Paintings

The significance of Kangra paintings, they use Hindi poetry as their source of inspiration; seemingly, they use real-time ambience. In Hindi poets, Love is the passionate intimacy of husband and wife, like Rama and Sita or Nala Damayanti or even Krishna and Radha as their modelled couples. Subordination of the female body and complete devotion is the central element of this ‘Love’; to some extent, the loyalty of women plays a significant part. When Kangra school uses those texts to narrate Love and Relationship, they create the ideals as characters of making Love and intimate relationship.

According to Randhawa, ‘Love comes from the Hindus, as to the ancient Greeks, after marriage. When the term lover is used in poetry, it is often synonymous with the ‘husband’. The conception of Hindu love is not liaison but married Love, a love which is the fruit of long association in the cares and responsibilities of home and children. Even in present-day India, pre-marital chastity is preserved and post-marital fidelity is honoured and widely prevalent, particularly among people not touched by modern education and cinemas’.

Love, Romance, and Portrayal of Women in Indian Miniature Paintings

Krispin Joseph PX, a poet and journalist, completed an MFA in art history and visual studies at the University of Hyderabad and an MA in sociology and cultural anthropology from the Central European University, Vienna.