What Defines the Later Work of Lucian Freud?

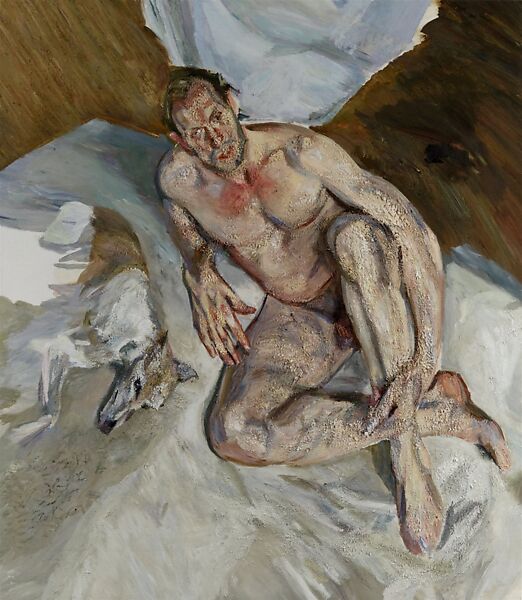

Lucian Freud is widely considered one of the greatest painters of the 20th century. In fact, his style is unparalleled, and his force is so strong and fervent that he has left an incredible mark in the world of art with his works on the human form. His late years, leading up to his death on July 20, 2011, at nearly 89, were a period of tremendous intensity and trance creativity that both anchored and altered his art. His last, unfinished work is a portrait of a naked man and a dog on a large, square canvas, showing the keenness with which he represented his subjects’ raw essentials even in the harshest situation of his physical decline. The following critical essay explores key facets of the later work of Lucian Freud-the unusual approach to portraiture, the changes in his last years, and their influence on his artistic legacy.

Dynamic Creativity in Late Period

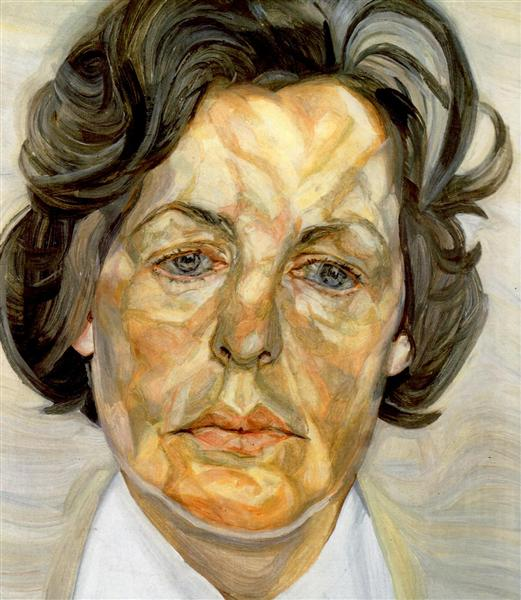

Freud’s late period was one of dynamic creativity, during which some of the best works were done. His physical affliction did not prevent him from working as intensely as ever, with 6 to 18 months on a single painting quite usual. His paintings show his peculiar brushed strokes and rich palette; though the incomplete dog points to one of Freud’s most salient aspects: his meticulousness, often reaching up to laboredness, in doing the work. His commitment to his craft was unremitting, as testified to by his last and unfinished portrait of a naked man with a whippet-a pursuit of artistic perfection if ever there was one. Indeed, the stylistic transformation of Freud in his later years in art is just a manifestation of how he was committed to the craft and how he contradicted conventional norms and clashed with their dominance. Early in his career, Freud was a precise, flat portraitist, but his eventual style was utterly changed by his friendship with Francis Bacon that began in the late 1940s. The evolution from an earlier, more conservative style toward a more textured, layered approach is evident in paintings like Woman in a White Shirt (1956–57). This evolution not only marked a departure from prevailing movements like Abstract Expressionism and Pop but also underlined Freud’s determination to explore and enrich his artistic vision.

Stylistic Changes and Artistic Vision

The effect of this stylistic change is particularly evident in Freud’s later work, with thickly layered paint and sensual, often naked, forms. Freud’s aversion to publicity and his emphasis on “the work” did not obscure the impact of his personal charisma and intensity. Despite his relative shortness, Freud was an imposing figure, known for the intensity of his gaze and private nature. His belief that the artist is as invisible as God in nature shows, in fact, how thoughtful he was towards letting art be at the front rather than the personality of the artist. Freud was a man quite committed not only to the technical aspect of his work but also to confronting his sitters. To Freud, his portrait work was immensely detailed and intimate. David Hockney’s sitting for Freud underlines the painstakingness of his process. Hockney remembers the long, intimate ordeal of sitting for Freud-more than 120 hours of sitting and talking. Indeed, the sheer intensity of Freud’s gaze, the slowness of his work, speaks volumes of his method as one of profound scrutiny, visual and more akin to knowing the subtlety of movement and expression that crossed the face of his sitters.

Methodical Approach and Artistic Process

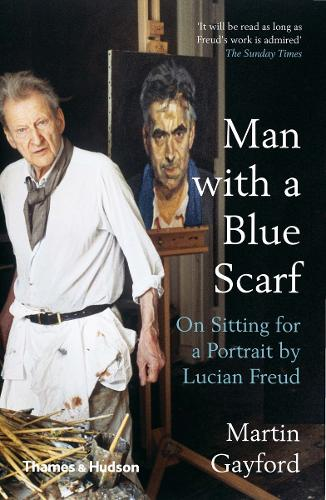

Martin Gayford’s Man with a Blue Scarf offers further insight into Freud’s methodical approach, characterised by constant muttering and adjustments. Freud’s deep concentration and commitment to precision are evident in his careful deliberation over each brushstroke and the frequent re-evaluation of his work. His self-identification as a “biologist at heart” reflects his rigorous and scientific approach to painting, as illustrated by his use of clean cotton sheeting as an apron, careful color mixing, and left-handed technique.

Studio Sessions and Personal Engagement

Studio sessions with Freud, though often characterized by their grave seriousness, were yet imbued with a festive air of abandon. Sitters basked in the warmth of Freud’s hospitality, above all in singsongs, shared tales, and fine victuals. Freud’s apparent abandon was calculated: through careful observation of his sitters in states of ease and disease-through hunger, caffeine jags, hangovers-the painter aimed for an ultimate record of flesh and blood, sense and psyche. This engagement beyond mere observation with the subject brought great self-awareness to their sitters. The experience of sitting for Freud, according to Jeremy King, a restaurateur who sat for him, was meditative, emphasizing how extreme his exposure and self-awareness were when he was being painted by him. The deep engagement wove a dynamic: it was personal and profound. His near playful references to his grandfather, Sigmund Freud, and the concept of psychoanalysis found in his work point out an ambivalence toward the field. Much of his work seemed to have an intended sensuality and even intimacy: the warmth of the studio, the close physical proximity during sittings, the nudes or “naked portraits.”.

Personal Life and Artistic Impact

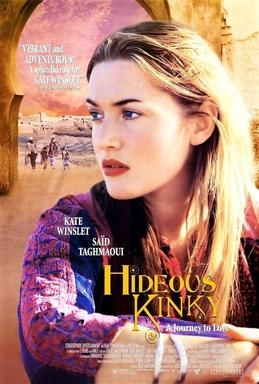

The complex life of Freud-especially the nature of his relationships with his sitters-adds to the works produced by him layer upon layer. His portraits included many women, some of whom became his lovers or mothers of his children, reflecting a profound interplay between art and intimacy. With his first wife, Kitty Garman, Freud had two daughters; his second wife, Caroline Blackwood, did not have his children. His relationships weren’t limited to marriage but included several women with whom he had children and mentioned above Suzy Boyt and Katherine McAdam. He proclaimed himself “selfish” and didn’t feel any “regular paternal duties,” Freud remained close to his children and other sitters through his art. A glimpse about what Freud’s parenting could be like was given by Esther Freud’s novel-turned-film called Hideous Kinky, and Rose Boyt’s writings. Indeed, the sittings themselves were devoutly meditative experiences for his children, full of both artistic and personal epiphanies. That Freud paints his daughters, among other close relationships, would suggest how his art weaves in and out of his personal life, reflecting professional dedication with complex familial dynamics.

Legacy and Final Works

During the latter years, Freud was deeply aware of his own mortality, working longer hours and maximizing output. Equally significantly, he found the chance to work with William Acquavella, a New York art dealer, essential. Support from him not only cleared Freud’s huge gambling debts but provided a much-improved financial position that allowed him to continue to focus on pure painting. His later years would narrow his world to the places that were familiar for him: the studio and old favorite restaurants. The portraits of younger sitters, like Alexi Williams-Wynn, are tight-skinned and charged. This is in keeping with the impact that Freud had on those around him. The late portraits, such as The Painter Surprised by a Naked Admirer and Last Portrait of Leigh, testify to Freud’s engagement with minute, intimated capturing. His work remained autobiographical, connected with his relationships to the sitters and his own reflections upon life and art. The work with his art was one means by which Freud could feel connected with the world and with the loved ones surrounding him when age and illness began to restrain him.

Retrospectives and Conclusion

Major retrospectives celebrate Freud’s life at London’s National Portrait Gallery, at Blain/Southern in London, and at Acquavella Galleries in New York. These shows give comprehensive insight into his portraits and drawings but signal mainly the impact of his work within the art world. As Freud’s last portrait, Portrait of the Hound sums up his unending commitment to work and his resolve to do as much as possible before his death. It was a deep commitment to art in general that marked these last years of Lucian Freud, characterized by an unrelenting work ethic deeply engaged with the subject at hand. His late works, including the final, unfinished portrait on which he is working, show an exceptional intersection of technical mastery and personal intimacy. Freud was to leave behind him a legacy of capturing raw bones of the human form and character that belied all traditional expectations of portraiture, making the art world stand in awe of his works. His adherence to his craft, even when his body shows obvious decline, testifies to his artistic vision and enduring influence.

Freud, Interrupted by David Kamp, Originally published in Vanity, 16th Jan, 2012