In the exhibition “Tree and Serpent” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, curator John Guy takes visitors on a journey through the mesmerising world of early Buddhist art in Southern India. In the recent thread of tweets by notable art historian William Dalrymple explains the show offering a fresh perspective, shining a spotlight on the largely forgotten masterpieces that have emerged from recently excavated sites like Phanigiri, some of which have never been seen before, even in India. The exhibition, which also features stunning pieces from lesser-known sites such as Kesanapalli in Andhra Pradesh, provides a comprehensive and breathtaking insight into the artistic achievements of the era.

Just back from New York where I spent the weekend making a deep dive into the utterly wondrous new show of early Buddhist art @metmuseum, Tree & Serpent pic.twitter.com/8SXC6MViHP

— William Dalrymple (@DalrympleWill) July 24, 2023

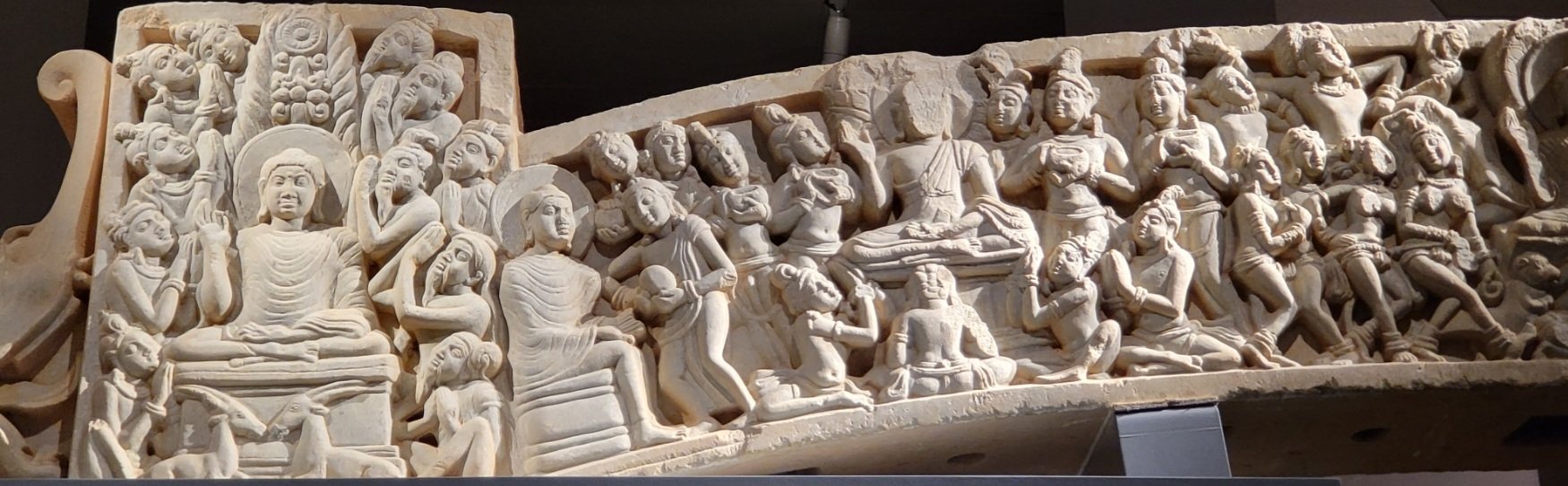

According to Dalrymple, the curator’s meticulous curation has brought together a collection of exceptional quality and condition. The Phanigiri material, in particular, stands out as a testament to the exquisite craftsmanship of its time, preserved in mint condition, as if it were carved yesterday. The inclusion of such pristine artefacts provides a rare opportunity for art enthusiasts to experience early Buddhist art in all its splendour and vitality.

Dalrymple tweets, “Tree and Serpent” effectively illustrate the magnificence and originality of the sculptures produced in sites like Nagarjunakonda, while also revealing the vastness of early Buddhist art in the Deccan, particularly in Andhradesha. This region, under the Satavahana and Ikshvaku dynasties, proved to be fertile ground for the flourishing of the Buddhist sangha, an aspect that has not received as much attention in modern times.

One of the most intriguing aspects of the exhibition according to Dalrymple is how it challenges common perceptions of Buddhism. Unlike the more familiar images of meditating Buddhas from later periods, early Buddhist art exhibits a diverse and complex theological landscape, deeply influenced by the cosmology of pre-existing animist cults. The artworks display inscriptions and carvings that honour guardian gods and tutelary deities residing in the natural elements, such as trees, stones, and water. These divine beings were believed to possess the ability to protect, attack, or even possess humans and monks in their vicinity.

A prominent figure showcased in the exhibition is the snake king Mucalinda, who famously sheltered the Buddha during his deep meditation in the sixth week after attaining enlightenment. The striking depiction of the Nagaraja enveloping the Buddha in his coils, with his hooded canopy providing shelter, is a captivating representation of this significant event. The presence of an empty throne and pair of footprints further alludes to the Buddha’s connection with the divine, while the wheel symbols on the footprints signify his role as a just ruler, guided by the principles of Dharma.

The prevalence of snake deities like nagas during this period is also noteworthy. Revered for their association with fertility and protection, these entities were an integral part of the monastic life and worship during early Buddhism. Through this exhibition, visitors gain a deeper understanding of the rich and intricate religious beliefs that shaped the art and culture of the time.

“Tree and Serpent” at the Met Museum is a groundbreaking exhibition curated by John Guy, shedding light on the extraordinary world of early Buddhist art in Southern India. With a captivating display of masterpieces from recently excavated sites and lesser-known locations, the show challenges preconceived notions about early Buddhism, revealing a vibrant and multifaceted theological landscape. This exhibition is not only an awe-inspiring ambassador for the arts of ancient India but also evidence of the Met Museum’s dedication to presenting lesser-known aspects of history and culture to its audience.

The Buddha statue discovered in Egypt indicates trade with ancient India

Iftikar Ahmed is a New Delhi-based art writer & researcher.