What qualifies as political art? Is all art political, even art that makes political statements? Since the definition of art is a complex question, so are the responses. Does art contribute to political discourse, or does it only mirror the conclusions drawn from political philosophy and political science?

Where did we get our knowledge of art and politics? We converse with friends, family, and neighbours, read blogs, newspapers, and magazines, watch TV news, listen to patriotic music, celebrate the Fourth of July, sing the national anthem before baseball games, and absorb the teachings from our early political socialisation. The list is endless. We are constantly exposed to political messaging at work and play. We are generally oblivious to the political messages we are told to. Yet, they infiltrate our subconscious and have the power to influence our thoughts, beliefs, and behaviours.

It is possible to wonder what function such politically discursive art serves. Therefore, the issue to be addressed is whether politically discursive art can add something new to the political discourse on particular subjects or is just a rehearsing of viewpoints developed in other fields.

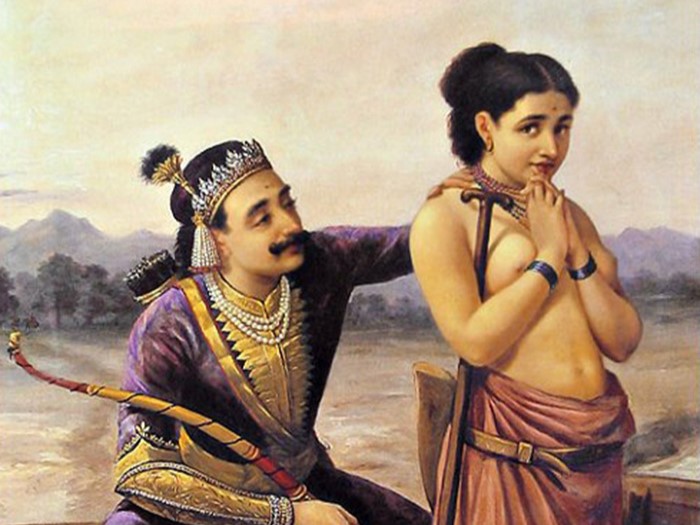

Defining political art is a difficult task. Opinions on what constitutes political art vary, starting with the notion that all art is political. Politics fluctuates throughout art history. Suppose we first confine our analysis to the limited scope of art politics as articulated by the subjects of artworks and the discourses surrounding them. In that case, we find that art politics rises and falls and can be quantified in a way that makes sense: there is more politics in some art historical periods and less in others.

Presumably, these “less” and “more” arrive at absolute levels at the extremes of these waves, and we can hear arguments that politics in art is no longer relevant or that art can no longer exist independently of political conflict. Acknowledging how politics and art intersect and diverge based on artistic trends and discourses is not inherently childish. However, a structural requirement for work with a more persistent political quality is also required.

It was a long journey, from cave drawings to movies to social media. We were united throughout the trip by artists and storytellers who provided us with standard frames of reference and shared humanity. One type of modern art is the movie. It is a hybrid of art, commercialism, and expressiveness, like the earlier art forms—music, painting, and sculpture.

Whether it is “political art,” “activist art,” “socially involved art,” or none of the above, art is political. It is also clear that artists’, curators’, and critics’ awareness of art’s institutional or structural politics varies over time and is resurrected at other times. Furthermore, a broad spectrum of viewpoints is predicated on the idea that art is inherently political. On one extreme of the spectrum, art is defined as a specific endeavour that, by its very nature, defies the social order in which it exists. On the other hand, because of its material, social, institutional, and economic structures, art participates in privilege and power.

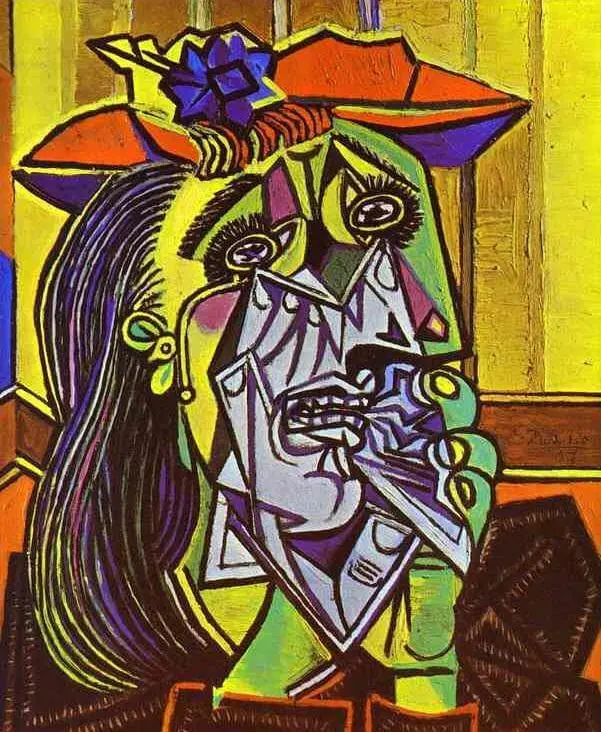

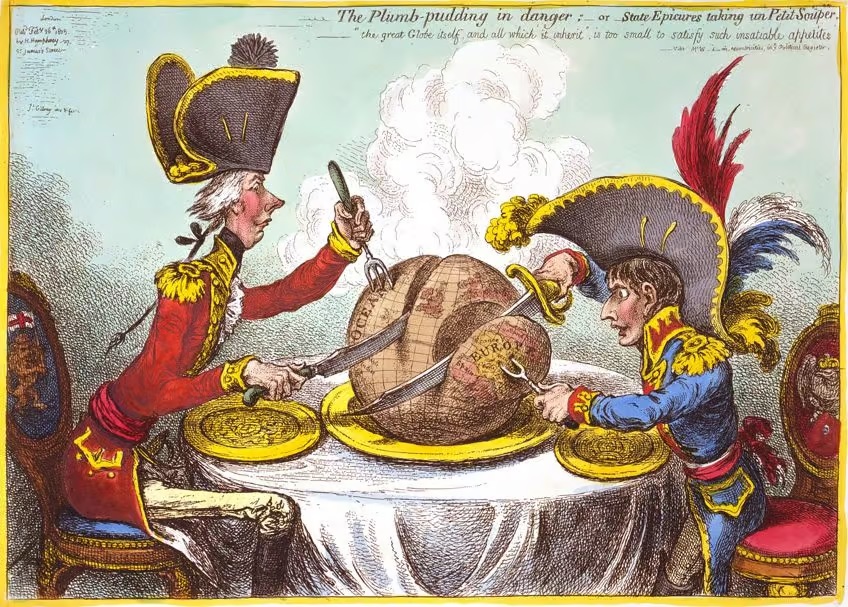

Politics has always been a part of art. The relationship between artists and politicians as critics and advocates of authority is exemplified by the works of Picasso, Wagner, Trollope, Daumier, and Nast and Trudeau cartoons, among other artists and political figures. As with Cold War Soviet propaganda posters, art has frequently been employed to uphold the interests of the in-party. These eye-catching posters promoted loyalty to the state and patriotism. However, art has often served as a status quo critic, exposing and questioning authority through prodding and poking.

A further perspective on the idea that art is inherently political contends that because art is protected and preserved by various legal, regulatory, educational, and civic initiatives, its independence is a political achievement. It’s also not been too tricky for critical theorists to create cunning traps and reintroduce politically reticent artworks onto the political map despite the complex conceptual framework that upholds art’s normative autonomy.

An excellent photograph conveys more information than just the picture itself. It narrates the tale contained in the image. Perfect art transcends the things we see; it gives us insights and meaning and transcends ourselves. Several famous photos from the Vietnam War were captured during the conflict. They went viral around the world, exposing the atrocities of war in general and the effects it had at home when demonstrations turned violent. The various ways that the nuanced approach of “doing art politically,” the critical depth of institutional analysis, and so on have been criticised as philistine and didactic in comparison to political art, propaganda, and Socialist Realism. In contrast to the detailed destabilisation of contested interpretations, direct social participation, and rejecting art’s compromised institutions, the depiction of politics in the substance of artworks and the behaviours of “commitment” and “tendentiousness” can seem unsatisfactory.

The first belief of the argument is that reasonable subjects, at the outset of any political inquiry, ought to aim for the idealised state of political art; it seems evident that the subjects ought to strive for impartiality and public-mindedness; reasonable subjects and objective style of discourse pair well; they are the model enquirer and the model medium of any intellectual investigation.

A demonstrator throwing a shoe at George W. Bush, a crowd of Iraqis toppling a statue of Saddam Hussein, and US troops rolling into Baghdad were just a few of the iconic images captured during the war in Iraq. However, the photos released from the Abu Ghraib prison in 2004 horrified the world. They revealed the brutality of the occupation, the sadistic decline of soldiers in combat, and the depravity of US policy and leadership. What is art, in the sense of photography, that brings attention to a subject and events?

The inclination to reject all alternative ideas and approaches to politicising art in favour of one understanding of art politics or one set of politicisation strategies characterises the history of modern art; rejecting any styles, techniques, and methods is necessary.

These conflicts have taken place in discussions about socialist realism and modernism, realism and naturalism, avant-garde and kitsch, Brechtian Epic Theatre and Aristotelian drama, making political art and making art politically, and, more recently, interactive versus participatory art, conviviality versus antagonism, and the difference between “being the change you want to see” and criticising the society as it is.

José Clemente Orozco: Art of Political Murals and Social Revolution in Mexico