Krispin Joseph PX

No one can tell the meaning of the colour black quickly. Black is a colour or the mindset or conditions that some people encounter and face in daily life. Grey or black colour may be the reason for exclusion from the elite space, and that makes sense in some spaces. ‘Who are these black people? Why are they here?’ These questions are prevalent in Indian situations, especially after the saffronisation. That question makes another sense outside India. In some countries, Indians are treated as grey or black-skinned people.

Dravidian skin tones are also poorly treated in Indian whitish locations and spaces. Skin tone is used as a tool for exclusion and ignorance. Black is a sensitive topic in art and literature because of the people curiously working behind this ‘Black lives matter’, and ‘Dalit lives matter’, political sources of thinking and practising for many people. The reason for this ‘think dark’ is because of the series of paintings by Devi Seetharam titled ‘Brothers, Fathers and Uncles’ in Kochi Muziris Biennale, in Aspine wall, Fort Kochi.

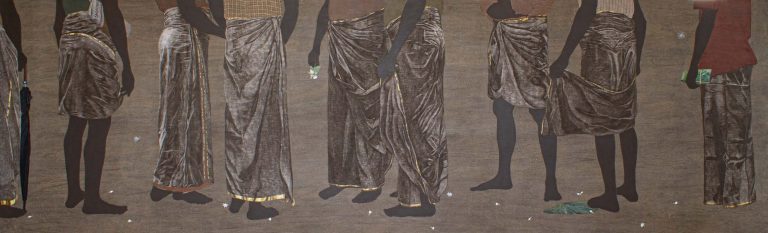

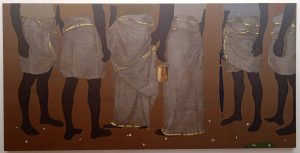

I think a lot about the presence of ‘black’ in this painting. The representation of the colour black in work is conspicuous and debatable. Artists depict the lower body part of people who wear Mundu (the local term of dhoti) in the golden line (the local word is ‘Kara’) border and other types to narrate the heterosexual male bonding in social spaces and the extent to which these performed masculinities further the entrenchment of patriarchy. Public space and the presence of males and the absence of women are crucial topics, and visual stories of these social phenomena are essential for understanding these things. Generally, gatherings are male in India (religious worship or political rallies), but artists looked into the Southern corner of India, her homeland, Kerala. She sees some exciting layers in this male-dominated public life and the expression of patriarchy in public space.

Males validate themselves through this dhoti, and the style of wearing that dhoti expresses the authority of the occupying space. The artist follows these subjects for a long time to document in photography. In recent years she has started to paint those phenomena from photographic references, reorganising them to her whims, exerting agency over these contingent social gatherings to which women rarely have access.

Artists remove that masculine bodies from the contextual markers and place them in a context of patriarchy; everywhere, these phenomena are aptly coupled and endowed with many things.

‘These everyday assertions by men through history, clad in their traditional attire- which is also a symbol of their given freedom and power- acquire the tenor of an urgent call for change in the sprawl of floral debris at their feet in Devi’s work. The symbolic power of this attire is also articulated in her compositions which situate the viewers’ gaze close to the ground with no choice but to glance upwards to the waists of her subjects’, write Anushka Rajendran in the concept note.

The process of revealing the idea of masculinity is impressive in this canvas, entangled with situations, nature, seasons, and landscapes. There is some chaos about the colour black and the body language of the people that artists narrate in the compositions. Who is these people, where do they come from, why are all thin, and does no one come from a ‘fatty’ climate? These people not only come from a black but ‘lower’ living background or labour class. Why do artists bring thin people? Why she doesn’t depict a ‘giant’ man or a fatty figure to get the other class, and why only narrate the slender body of the people?

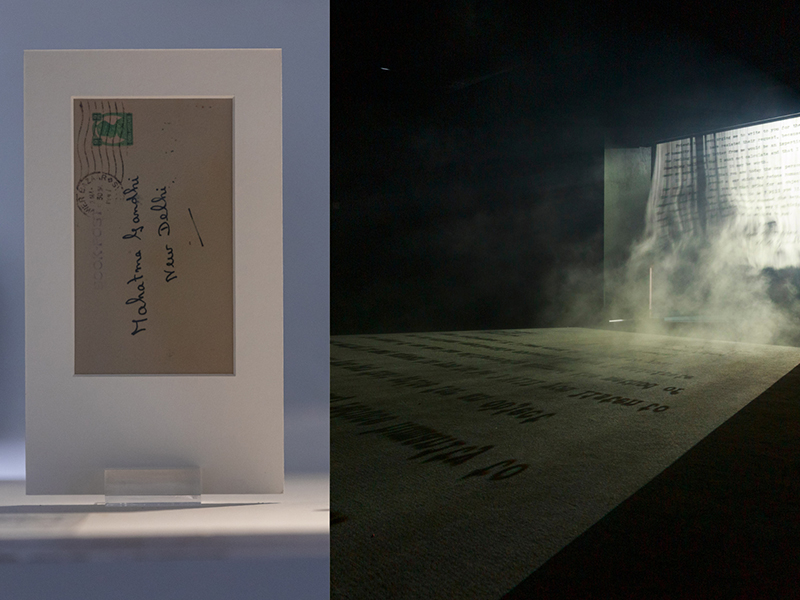

‘I started this series in Australia, and I felt I am an outsider in that white space. I stayed in many countries with my father. I was an adult when I reached Australia. That life gives some idea about the otherness of colour, why I treat like this a lot. I felt I am brown. Then I used that colour tone as a pride to depict that dignity in my canvas. In India, discussion on colour is entirely different in tone and volume. I realised how am I treated outside my geographical location, and I’m aware of how I get treated in my country. I stand between two narratives and social situations. I am fair, carry white skin linage in my country, and am treated as brown in other countries. And I am trying to narrate the patriarchy in our living space that brings my othering section of the society. As a woman, I felt mistreated in this society, with every public space occupied by males. Any public zone is inhabited and celebrated by the male and their masculinity. I started to question this male-dominated- masculinity in my canvas’, Devi Seetharam said.

This idea of masculinity in South Indian artists carries from outside India, and ‘blackness/greyness is a representation of ‘Indianness’ outside India and representing a whole country. ‘The artist has omitted signs of lush, superficial impression and instead constructed a focused dialogue of her intention’, Michelle Caithness writes. In this series of paintings, the artist’s intention is narrowly merged with the ‘colour black’ and the perspective of black. How can we take this visual experience of masculinity through a very complex window of ‘blackness’ and who we are ‘black or white? The ongoing discussion on and about ‘black art’ created a reading possibility of anything under the black art domain and denied if that is not representing ‘blackness’. The term ‘Black’ is not a colour that represents a life in which one is underrepresented anywhere. This work brings a critical view of public space mixed with Kerala-Malayali climatic zones, and masculinity and public space became a questionable discussion area.

It must be said that this system did ensure a certain degree of female autonomy in the past, especially concerning familial economics. However, the structural changes brought about by Western modernisation have long since pushed such claims into the realm of a distant memory, writes Jones John on her website, and these things are dealing with a subject of visual experiences.

Krispin Joseph PX, a poet and journalist, completed an MFA in art history and visual studies at the University of Hyderabad.