Smriti Malhotra

Since the beginning of time, our ancestors have left sacred images of the female form. From the caves of Lascaux in France to the terracotta images found in the Indus Valley civilisations the art and artefacts which represent humans’ earliest myth making tendencies, indicate a deep reverence for life and, in particular, for the great mother. ( Goddess – Mother of Living Nature – Adele Getty, 1990)

The goddess is both universal and permanent in the imagination, and she is the mother of the world, giver of life, the great nurturer, sustainer and healer. Yet, she is also the bringer of death, the one who grants immortality and liberation. The goddess giveth and the goddess taketh away. She is capable of infinite compassion in one form and of total annihilation in another. She is the embodiment of what we know as life; her story is as old as life itself, for she is life itself. This is a story of the lesser known Goddesses of Gujarat, who are immortalised on textiles through the beautiful art of block printing and kalamkari.

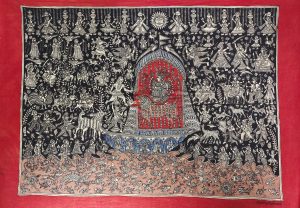

In this article, we shall be delving into the world of Mata ni Pachedi, the painted textile art of Gujarat that has been gaining momentum over the past few years. In this essay, we shall be learning about how the textile is made, who are the manufacturers of the textile tradition and shall briefly touch upon the iconography painted on the textile as well as its ritualistic uses. Mata ni Pachedi is the story of Mother Goddesses represented on a ritualistic textile that serves as a great reminder of the importance of vernacular artforms in India. Indian crafts aren’t simply serving an aesthetic and utilitarian purpose but are sacred and visceral in their own rights. These are the textiles used as Temple Tents for Goddesses, in Gujarat. Recently, the craft of Mata ni Pachedi received a Geographical Indication Tag from the government. The GI tag signifies a product coming from a particular geographical location and possess qualities of great reputation. The GI tag gives the product and that region a specific right to make the product/craft and cannot be made by a third party and or any other geographical region.

Now, coming to the actual textile, several terms are used to describe these temple hanging textiles in Gujarat. The term most often found is Mata ni pachedi, it is a relatively modern word that came into usage.While Mata ni pachhedi means the backdrop of the mother goddess, Mata no Chandarvo refers to the canopy of the Mother Goddess.The pachedi is popular amongst the shepherds and cowherds and is sold in two different sizes for waist cloths and dhotis with a plain field of either white,red,maroon with plain borders and wide across borders. Pachhedi fabrics are thus single coloured, mostly white, coarse cloth pieces that are worn as garments by men. (Moti Chandra, Temple Tents For Goddesses in Gujarat,India, 2013) Unlike the popular notion that the tradition of Kalamkari is only found in Andhara Pradesh. They are found in Gujarat in the form of Mata ni Pachedi.

Manufacturers of Mata Ni Pachedi:

The textiles are made by people belonging to the Vaghri community in Gujarat, essentially now restricted to Ahmedabad. The community is a lower caste in Gujarat, centuries ago they were termed as the ‘untouchables’ Hindu caste, a semi-nomadic group that travelled from place to place in search for livelihood and work.They built temporary homes and even temporary shrines and some believe that is how the Mata ni Pachedis started getting made. These are icons of Mother Goddess made on a large textile cloth that is often used as a temporary shrine and a travelling shrine. One has to simply unroll the fabric and flung it across an area, either on a wall or on poles and the shrine of the Goddess is ready!

There is also an interesting legend about how this art of textile painting/printing reached the Vaghri community. About 300 years back the Chhipa (‘one who prints’) community used to paint images of goddesses and other decorative motifs on textile with kalams (bamboo/wooden sticks or twigs) and also developed carved wooden blocks to print such images for quicker representation. These were the people who spread this art in the religious and cultural life of Gujaratis. Once, during a period of economic deficiency, Chhipas sold their wooden blocks to a Vaghri trader of Viramgam. This Vaghri family themselves started textile printing with the help of those blocks and developed this unique style of textile painting and printing. Afterwards Vaghris migrated to Ahmedabad to expand their business.

Making of Mata Ni Pachedi:

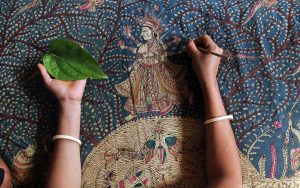

The base of the textile is always a stern khadi fabric as it is more coarser and keeping longevity in mind of the textile shrine. The khadi pieces are cut to the size (approx 63-72 inches for the canopy) and washed and seasoned properly. One important element to note is that different communities and groups of people are involved in the making of a Mata ni Pachedi. There are the washers and mordant dyers belonging to a caste originally hailing from Rajasthan, there are the wooden kalam and wooden block makers who belong to the Chippa community are involved in the process as well.

The washing of the fabric involves dipping the fabric in myrobalan powder and then castor oil. The fabric is washed with these mordants a few times that gives it a yellow tinge. Once the cloth is sun dried, it is ready for painting and block printing. While elaborate wooden blocks are used to essentially chart out the entire textile starting from the borders (chaukhat) to the main icons of the Mother goddesses, the bamboo kalam is dipped into ink and used to connect the missing lines, fill gaps and add intricacies to the icons made on the fabric, all the while correcting any discrepancies within the painted textile as well.

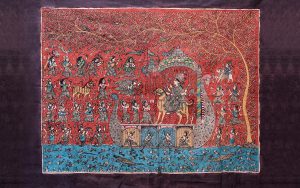

The artist then fetches a can of yellowish liquid called limbai – watery mixture of alum and tamarind flour. This liquid is also dabbed onto the required space of the textile. The central figure of the mother goddess is to be painted last. Finally after everything is covered, he dabs the feet of the mother goddess first, and then slowly moves up to do the rest of the textile. The textile once covered in alum mordant and painted is dried and washed. Once dried, the textile is dyed by professional Muslim dyers belonging to a particular community within the region, who dip it in alizarin that gives it its red hue. The Rangars as the dyers are called, dye it a few times and bleach the textile by dipping it into camel dung which works as an organic substance. In some cases, the Mata ni Pachedi are often not dyed but simply painted by the artisans from the Vaghri community, who simply draw upon the fabric and paint on it either using organically made colours or artificially bought ones too, which is seen to be the case currently. The newer Mata ni Pachedi that you see being made have that new, artificial sheen while the older and traditional Mata ni Pachedi were simply made with 3 colours – white, black and maroon and were intricately painted upon with various elements and storylines and narratives flowing in each register of the textile.

Iconography in Mata ni Pachedi:

Humans are believed to live on hope and faith in God. They have to face several risks, hazards, and challenges. If they do not have belief that someone unseen is protecting them they will be worried and thereby suffer insecurity. Especially in a country such as India wherein health structures may lack in some aspects, the faith redeems hope within people and people seek blessings and support from an unknown, indescribable supreme power which is God and in this case local Goddesses.

One of the most striking features of rural India is the worshipping nature of Mother Goddesses, the devi cult is strong in this country, with a number of Devis being preached not just in the main Brahmanical pantheon of Gods and Goddesses but also locally. Although the act of preaching main Brahmanical Gods and Goddesses is carried out by the villagers but in less interest. There are multiple Mother Goddesses, every village has a specific dedicated Goddess, they have their own vehicles. Mother Goddesses are the central theme of the textile, however you have the known popular stories from Ramayana and Mahabharata also showcased.

The main Goddesses represented in a Mata ni Pachedi are – Ambika, Kalika, Bahuchara who are linked to the Shakti Pithas i.e. the main centres where parts of Uma/Sati’s body fell in different parts of the country. There are Goddesses that descend from local myths, Goddesses of sickness and plagues, and Goddesses with supernatural powers, and protectors of a region or community. These Goddesses have their own vehicle which is representative of the Mother Goddessses riding them, one can spot animals such as Crocodile, peacock, buffalo,lion, donkey, gajsinha,camel, and more. There are 12 Mother Goddess representations on these textiles which are Ambika, Meladi, Shitala, Bahuchara, Kalika, Vihat, Khodiar,Chamunda, Shikotar, Vaduchi, Momai, Hadkai, and Gel Mata, with a few Jal Mata’s and popular Hindu pantheon Gods and Goddesses such as Ganesha, Shiva, Krishna and other important mythological tales. Other elements that one can spot in these textiles are worldly elements of Sun, Moon,Divine beings,Animals and other figurines, each having their own meanings.

Ritualistic Practices of Mata Ni Pachedi:

It is believed that the textile was made to essentially fight the temple ban by the Hindu, dominant castes of the country. When the people belonging to certain communities were banned from entering the Hindu temples, they decided to make their own shrine. This temple shrine is a living example of that retaliation.

The Mata ni pachhedi pieces are most exclusively used for certain ceremonies conducted by the lower castes and other small communities of Gujarat. Every year on different occasions, the families take out the shrine of the Goddesses and important rituals are performed around it. During theNavratri season, there are communities that are still practising this living tradition of setting up the temporary shrine for the Mother Goddesses in Gujarat. Traditionally, it is an all male ceremony that is conducted once the shrine is constructed, a priest is invited and he acts as a medium between the believers and these Mother Goddesses. The priests (bhuvo) are “possessed” and they represent the presence of a divine being within them during the ceremony. There are musicians, tale-tellers, and a sacrificial animal that is offered to the Mother Goddess.

The traditional Mata ni Pachedi has a deep significance in the lives of the people who make it. These textiles go beyond just being a way of living for the people of Gujarat, their faith and belief system is hugely embedded in these cloth pieces. The spirituality and potency of this textile is unlike any other, they aren’t just canopies that cover the shrines of Mother Goddesses for the underprivileged. These Goddesses on these textiles are the only idols they preach, she is their creator and protector.In an unjust world, where the underprivileged and lower castes still face disparities on so many fronts including entering a temple vicinity. This piece of textile provides them with hope and relief. In the face of adversity, one can turn to faith and art to find solace, and this textile art form combines the two beautifully.

Mata ni Pachedi textiles have gained a lot of traction over the years with a lot of contemporary galleries who promote indigenous artforms of the country have them in their collections, many Vaghri artists have gained popularity and have been travelling the country and internationally showcasing their beautiful creations to the world. The art form has evolved to include contemporary and modern elements and themes while still preserving its traditional and technical roots. While only a handful of people are practising the art of making these religious backdrops, the art still remains relevant for the art lovers and for art admirers. However, the century old artform shall hopefully gain more popularity due its recent Geographical Indication Tag and the art form shall live on for centuries to come.