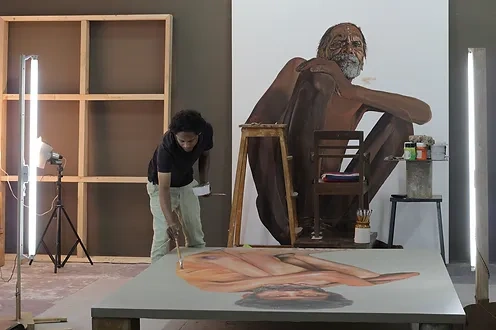

When pretty much every thing in the world today seemed possible with AI, internet, and cameras ever cheaper, one may wonder the point of creating images by hand; particularly hyperrealistic paintings. Why paint what you can photograph with someone quickly? These questions quickly faded when I found the work of Parag Sonarghare and suddenly, it all made sense as to why hyperrealism is needed for the movement forward in contemporary art. While Parag Sonaghare himself not only produces static impressions of reality, but rather evokes different layers of living societies and even plays a prominent role in bringing the marginalised voices under the projection. The hyperrealistic painting is not simply a form of reproduction, but represents an irreplaceable exploration of identity which would primarily given to the dynamic oscillating nature we encounter.

At a time when hyperrealism rife in painting can feel like anachronistic, Sonarghare’s obvious decision to paint hyperrealisticaly instead of taking photographs is telling in itself. This juxtaposition of realism and dreamlike subjective, oscillating between critiquing our societal ordinals and reverencing them, is truly representative of his work as a whole. But what does hyperrealistic painting do to open up a unique power of its own? Unable to take a photograph of these faces, these stories about social marginalisation? The response lives in the richness of intention, substance and naturalness that painting evinces; Parag transcends photography by invitation to a keen emotionality, bordering on corporeality.

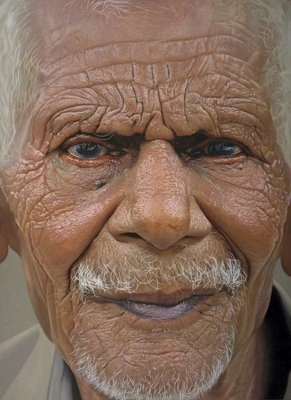

Hyperrealistic paintings have a subjective nature that is absent in the objectivity of photography. This occurs due to intentionality and subjectivity. In Sonarghare’s paintings, every stroke is intentional, carrying his interpretative lens, technical choices and emotional inflections. Sonarghare highlights the facets of a picture that can be more easily missed or diffused, and in his decisions on what to highlight: whether this is skin texture, an expression or depth of a wound — he argues for himself. This is how he connects the “real” and the “idealised”. His portraiture does not only present a face, it amplifies certain aspects of experience and existence within the subject – urging us to look past outward appearance and into more complex identities underneath.

Tactility and Texture Images are full of detail visually, but still tend to lack the material feeling that painting brings about. The hyperrealism of Sonarghare lures you to interact with the tactile aspects of his subject. The skin texture, the small blemishes, and the way the light shines off a surface— all these things are made in detail to create an intimacy that calls back watches to stay. He immerses us tactilely inside the photographs, he unleashes empathy-based interaction, only this time using some confrontation.

A painter can create a “more-than-real” depiction of its subject by suspending time, whereas a picture only records one instant in time. Sonarghare gives his pieces this timeless quality; although his faces might be anchored in a certain epoch, the people he depicts embody enduring social discourses. This deliberate timeless quality connects with the sincerity-driven introspection of metamodernism, giving his subjects a legendary quality that appeals to common human experiences.

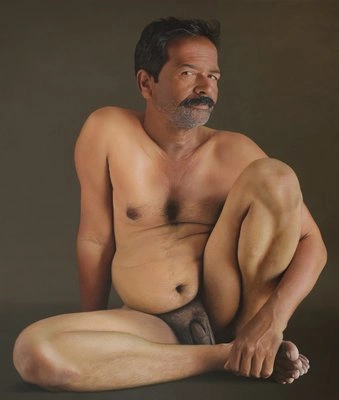

Hyperrealistic painting has an element of performativity, a stage for the artist’s multifaceted narrative to be played out. The effort of microscopic precision in Sonarghare creates a sense of life superimposed on overwhelming meaning, which draws away from static reality opening imaginations towards the kind of performative drama and viewership. The paintings each tell a story, a visual metaphor of silenced voices that goes beyond documentation. Sonarghare had positioned these individual stories on hyperrealism where each face and every flaw becomes a representation of our society to reflect upon. While there is great immediacy to photography—what Fenton called the magic of a suppressed reality, pressed against paper—the medium often possesses little symbolic depth because it tends to present rather than narrate, capture instead of interpret.

The laboriousness of hyperrealistic painting lends Sonarghare a particular vulnerability, the immediacy that may come from photography’s faster-developing and more aloof process. Each of these models is a combination of hours spent together, and as such reveal what seems an almost human connection between artist and subject. Such a careful, even slow pace, characteristic of the more empathy-motivated perspective, allows Sonarghare to present a complexity which builds in layers over time and through lived experiences—an evolution built on profound humanity and sentiment. At a moment when images are produced and consumed at lightning speed, Sonarghare’s work distils a heartfelt excavating process that testifies to the ability of art to ground us in larger scales of reality.

The work takes away this basic crux of hyperrealism not merely as a matter of fact and chosen technique but more to the integral flux between empathy, introspection, narrative strength that perhaps only can be achieved through photography. His paintings embody the spirit of our data-laden lives, where such oscillating realities—the hyperreal and the mythic; the social and the personal—give room for us to unpack both our complexities as well as how we relate to one another. It may be that hyperrealism is a medium that time should have passed over, yet Sonarghare proves otherwise as an artist — demonstrating quickly his place in this world as someone who invites us to see our surroundings anew, but in a way where we are not simply spectators passing through the peep holes of spaces; instead aspirants pulling back the curtain at every juncture.

Feature Image Courtesy: Gallery Splash

Iftikar Ahmed is a New Delhi-based art writer & researcher.