Introduction

Art mirrors society, with its cultural, historical and philosophical underpinning. One of the organising principles of Western art history has been the categorisation of the development of the arts into movements or “isms” such as Impressionism, Cubism and Surrealism, which represent identifiable styles, philosophies, and historical phases. Indian art, by contrast, is usually named by geographic and cultural contexts rather than formal movements. This divergence is based on the extremely contending historical, cultural and intellectual paths that Western and Indian art took.

The Foundations of Western Artistic Classification

Western art history, shaped by the Enlightenment, was all about reason, classification and linear historical progression. This intellectual model helped create systematic categories of art, in which movements were determined by philosophical and stylistic dogma. Examples like the emergence of Romanticism in response to the rationalism of the Enlightenment with its focus on emotion and nature, or the move away from Academic art in the Impressionists’ exploration of light and perception. This Enlightenment overdose has led the West to theorise and compartmentalise art into “isms.” It enabled art historians, critics and institutions to plot art’s history as a narrative of movements in succession, each of which responds to or builds on its predecessor.

Western art movements have often been spell out in manifestos or collective declarations. Simply put: a manifesto is a public declaration of a group’s intent and ideals, often written in the literary format of a manifesto or manifesto-style essay centered around a bold thesis, political statement, or artistic movement, such as the Futurist Manifesto, written by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti in 1909, which set forth the core principles that Futurism was built upon—celebrating the new pageantry and possibilities of technology, speed, and modernity. The Dada movement was similar in instigating anti-art to counter the atrocities of World War I, yet its artists declared they hated traditional beauty. These were concise manifestos that gave frameworks for expressing the various art movements. Artists coalesced around particular ideologies and from identifiable groups united by common philosophies, techniques, or goals. This clarity allowed art historians to easily label and classify Western art.

This move was consolidated within the Western tradition of art movements through institutions such as art academies, museums and galleries. These institutions were important for codifying movements that they often advocated or lent authority to their styles. Critics like Clement Greenberg and John Ruskin shaped our understanding of movements from Abstract Expressionism to the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, which only served to cement this approach, a process in which the emergence of art criticism as a profession played a part.

The linear narrative of artistic movements over time is one of the defining features of Western art historical narratives. The Renaissance, for instance, gave way to the Baroque, followed by Rococo, Neoclassicism and, finally, Romanticism. This chronology shows a Eurocentric view of progress and invention, where each movement responds to what came before it. The clear trajectory made it easy to put them into movements.

Indian Art: A Pluralistic and Regional Framework

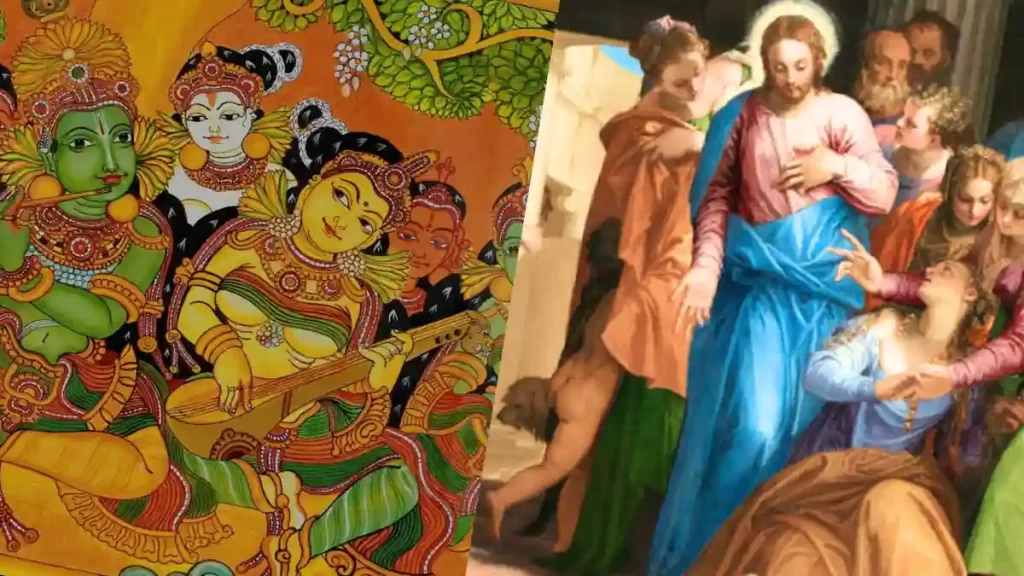

Unlike the Western art movements of Marxism, Cubism, Surrealism, Dadaism and whatever, owing to the cultural and linguistic diversity inherent in the Indian subcontinent, such a hegemonic imposition was always going to be difficult, if not impossible. The Indian art has always been reflective of its regional and cultural contexts and each region has given birth to its own artistic traditions. The traditional Pichwai of Rajasthan, folk Madhubani of Bihar and the Warli of Maharashtra may be unique artistic traditions in themselves, but they also contribute to a larger base of cultural creativity. Indian art does not follow a chronological linear, but has an interwoven development of traditions that is sometimes simultaneous, sometimes running parallel in the regions. This pluralism does not lend itself easily to compartmentalisation, as each tradition brings its own history, its own techniques and its own symbolism. Indian art has always embraced continuity — breaking motion is not so much it. Traditional art has coexisted with modern art, providing a mix of old and new all at once. For example, Raja Ravi Varma fused Western academic techniques with Indian mythological themes, bringing together traditional and modern art. Out of this, Bengal School of Art, spearheaded by artists like Abanindranath Tagore, revitalised Indian miniature painting techniques while also taking cues from modernism. This mirrors Western art, in which movements are often defined by radical breaks with the forms that came before. Because Indian art is so constantly evolving, it is less conducive to the kind of rigid classification by “isms” that has plagued its evolution.

Perhaps the biggest difference, though, between Western and Indian Art is philosophical. Western art often mirrors shifts in intellectual or political thought, while Indian art is inextricably linked to spirituality, mythology, and cultural identity. Indian temple sculpting and Patachitra paintings are two examples of traditional Indian art forms that arose from religious or ritualistic needs offering the symbolic meaning of the art rather than the stylistic evolution. These kinds of themes — spiritual and mythical, do endure even today in modern Indian art. These artists including M. F. Husain and Tyeb Mehta, used Indian epics and symbols that invoke content from the past, and find resonance in the cultural memory rather than finding consonance on Western art movements.

Modern Indian artists organized themselves into regional or ideological collectives instead of around wider “isms.” This gave birth to people like the Bombay Progressive Artists’ Group, founded in 1947 by veterans like F.N. Souza, M.F. Husain, and S.H. Raza, who all wanted to remove traditions and redefine Indian art for their generation in the post-independent era. Their works boasted a variety of influences, among them Indian mythology and European modernism, but the group was less a movement with a single manifesto than a regional collective. Likewise, the Delhi Silpi Chakra and such other groups of artists were more interested in promoting camaraderie and collaboration than in gathering around an ideological banner. These collectives showcase the regionally intensive, collaborative, amorphous nature of Indian art that can resist movement-definition.

The Impact of Colonialism and Decolonisation

Indian art is also influenced by its colonial past as much as its classification. Under British imperialism, Indian art was fetishised through Orientalism, which mythologised traditional art forms but dismissed those that were contemporary. Driven at least in part by this ongoing auto-critique, Indian artists and critics sought to reclaim their cultural identity by reinstating the regional traditions and local materials that had been central to India’s art before the British arrived, and rejecting Western models and frameworks. In the years following independence, Indian art underwent a process of decolonisation as artists confronted issues of identity, tradition, and modernity. This is more so because this process was not aimed at creating movements but rather exploring several strands of what Indian identity could be, thus further entrenching Indian art in a regional and pluralistic categorisation.

For instance, progressive artists like M.F. Husain and the Progressive Artists’ Group disrupted colonial-era category distinction through the incorporation of Indian subjects into modernist art practices. Amrita Sher-Gil also married Western artistic styles with Indian subject matter to engage concepts of identity and tradition. In these cases, it was also less an “aesthetic” or “technological” invention to create new movements than it was a multi-hectare search for the expression of Indian identity, echoing and reinforcing the regional, pluralistic definition of Indian art. The Madras Art Movement, which arose in parallel with the Bengal renaissance, emphasised the strength of the regional arts while also engaging with modernist modes of painting, demonstrating the way Indian artistic developments elude monolithic categorisation.

Conclusion

While Western art is sorted out into categories termed “isms” and Indian art into geographical backgrounds, the two methodologies to study the canvas diverge here. Western art history, formed by the Enlightenment and its institutionalisation, is built on this idea of linear progression and philosophical manifestos. On the other hand, Indian art, which springs from a field of cultural diversity and spiritual continuity, does not allow these ideas to be easily compartmentalised. These dualities may not represent better or worse but follow respective portfolios of a global logic classifying aesthetic practices. Whether compartmentalised by Indian art regionally, contextually, or thematically, to examine it as pluralistic and resilient, Indian art can be seen as providing a model for greying, divergent and contextualised artistic evolution that finds more value in continuity and diversity than it does in definitive and categorical classification. Comprehending these distinctions enhances our understanding and appreciation of both traditions, emphasising the universal power of art to mirror to and shape individual human experience.

Iftikar Ahmed is a New Delhi-based art writer & researcher.