The eighth iteration of Abir India’s First Take 2024 is about to engulf the vivacious city of Ahmedabad. This event is more than just a show; it is a demonstration of the ability of art to erase boundaries and captivate hearts. It’s important to consider Abir India’s extraordinary journey to this point as the expectation grows. Out of scores of entries, about 100 works would be picked by the eminent jury from India. The jury will select the best out of the lot and ten awards in total are awarded.

The show will also bring art lovers together, with dialogues, discussions and demonstrations with senior artists, art historians, art critics, curators and investors. For the First Take 2024, one among the eminent Jury is Gigi Scaria. Let’s know more about him and see what expertise he has to offer in Abir India’s First take 2024.

Artist Gigi Scaria reflects on his journey as an artist, the visual sensibility, and the role of art teachers and institutions in a conversation with Digvijay Nikam.

An artist who works across the genres of painting, sculpture, photography, and video installations, Gigi Scaria is one of contemporary India’s most innovative and distinguished artistic figures. The breadth of his work is truly astonishing and encompassing it invites the necessity of at least a monograph. Therefore, this article only promises a modest attempt at introducing the man and some of the ideas that have been central to his work so far.

Born in the village of Kothanalloor in Kerela in 1973, he did his BFA (painting) from the College of Fine Arts, Thiruvananthapuram, and an MFA (painting) from Jamia Millia University, New Delhi.) He has held several solo exhibitions at eminent galleries in India and abroad such as Chemould, India; Galerie, Christian Hosp, Berlin; National Art Studio, Korea; Aicon Gallery, New York and the Ian Potter Museum of Art, Australia. He was also among the five artists who represented India at the 54th Venice Biennale.

Scaria’s earliest instinct as a child was towards the aesthetic. In an interview he says, “When I could barely hold a pen or pencil I started drawing.” Those formative years were spent playing with clay mud after the school break. Partly, this was to later influence a sculptural imagination that has been so central to his work. Like many others, his forays into the art world involved copying the masters like Rembrandt, Michaelangelo, Picasso, etc whose works he encountered on the covers of Bhashaposhini, a literary magazine in Malayalam.

With a spirit to explore, not just the world but also himself, he aspired to move outside Kerela on finishing his graduation. After a detour through the city of Baroda in Gujarat, he landed in the metropolis of the nation, Delhi. The move to Delhi was to have a significant impact in reshaping the contours of his artistic imagination by making starkly visible the social, cultural, and political disparities plaguing our country. His work Elevator from the Subcontinent, a video-cum-sculptural installation created for the 54th Venice Biennale in 2011, is a powerful example of his interest in depicting, what one of his commentators has called, ‘the archaeology of urban life’. The viewer steps into Scaria’s structurally static elevator to travel through the various social strata that constitute the national capital by being made to see projections of the living space of disparate social classes. Imbued with a sense of claustrophobia, the experience is revealing of the unequal modernity we inhabit.

But often, the politics of the transforming reality around us is not so conspicuous. Sometimes, the movement of change is so slow, imperceptible yet regular that one day when we are made to behold our surroundings we are shocked by its incongruity with our mental images. In Face to Face, Scaria draws our attention to the unceasing transfiguration of our urban spaces, informed by desperate aspirations of becoming a powerful economy like our notorious neighbour, China. Done in 2010, a period when China was emerging as a singular economic and political force, the manipulated photograph juxtaposes two different places. The original photograph of a construction site along Delhi’s ring road is superimposed with images of buildings set in a row taken from Shanghai.

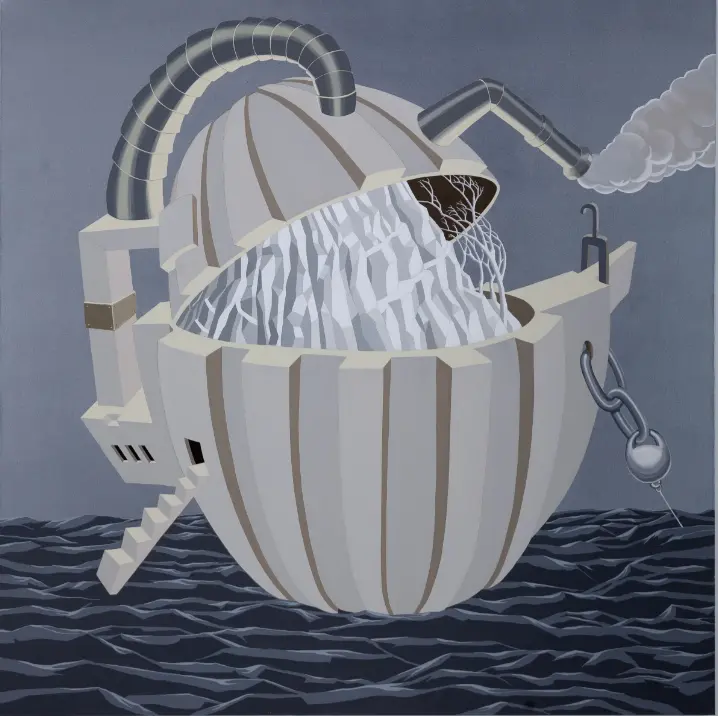

Trail, 2020. 36 x 24 in. Acrylic on canvas. Courtesy of Vadehra Art Gallery.

The surreal aesthetic of the photograph and its peculiar sculptural gaze are a recurrent feature of Gigi’s eclectic oeuvre. The ability to observe architectural forms with remarkable nuance and bring that structural imagination to conventionally non-sculptural forms like paintings and photographs is a testament to his unique style. Maybe this bears some connection to the predominance of buildings in his works. ‘Buildings’, he once said, ‘are much more like human beings in my paintings.’ They are reflective of the atmosphere and mood of the spaces we inhabit.

In a telephonic interview with the writer, Scaria, in his characteristically amicable and humble tone, notes that the visual sensibility of an artist is constantly trying to renegotiate our relationship to the everyday in order to defamiliarize the normal, the ordinary that escapes attention. Cultivating this sensibility is a difficult task and an individual pursuit. Speaking on the role of art schools in this context, he notes that, unlike other aesthetic forms like literature, music, or dance, having excessive guidance in art can often be detrimental to the development of the artist.

Given his involvement in art teaching throughout his career, for him, the role of institutions and teachers is to provide an encouraging environment for artists where their ideas and works can be critically assessed. Hence, the ‘necessary evil’ of holding hands in art must know its limits if art has to flourish. In that sense, the dichotomy of art as an individual journey despite being a social practice is very much alive in his thinking.

When asked about his process, Gigi noted that his perceptive sensibility is always open for stimuli from the environment he inhabits. And when something triggers his intellectual faculties with an idea, a lot of thinking is devoted before proceeding with execution. Therefore, as spectators we should bear in mind that whenever we encounter a Gigi Scaria work, a lot has gone into it. A kind of spontaneity or trial and error that we traditionally associate with artists is not his cup of tea. He also cautions us that sometimes the claims of spontaneity we hear by artists are made for the sake of it, or for garnering false praise of artistic genius.

Moving on, in recent years, Scaria’s attention has turned to more global and humanitarian concerns. “What does it mean to be human? What has the civilizational trajectory of human endeavours yielded? Where are we today? And where are we headed?” are questions that his multimedial work has consistently posed for the viewer. In Fall we see a human figure, supine, as if exhausted or maybe dead from a fall. Is it the fall of Icarus, a metaphor for humanity’s overarching ambitions? As the critic Premjish Acharya notes of the work, “The journey of man beginning from the Garden of Eden will eventually end in the Golgotha, and the resting place will not be in the clouds. The sanctuary is breached and humanity is reduced to a biogenetic structure, exposed to the possibilities of its extinction like never before.”

In the mayhem of contemporary crises that are unfolding all over the globe not just in terms of wars and political turmoil but also the larger threat of human extinction because of climate change and biological threats, Scaria finds some scope of – if not redemption than at least – hope in the creative spirit. While Gigi is optimistic that several platforms have sprung up today for nurturing that spirit in the form of art schools, better gallery networks and art foundations with grants, he is also sceptical of this burgeoning space.

In his opinion, a tight institutional framework can sometimes constrain the artistic sensibility in multiple ways: by imposing the organizations agendas and aspirations on the artist, by compromising the autonomy of the jury, by implicitly supporting the vocabulary of ‘trends’ and by constructing a cultural discourse around what it means to be an ‘artist’. We notice in recent times the production of a particular artist figure – one who, more often than not, speaks English; is eloquent in discussing one’s work; is adept at art history, dresses a certain way and is schooled in mannerisms.

How do we respond to such challenges in our collective journey toward a redeeming future? Maybe the answer lies in noticing the discursive frameworks operating in our society and building more sincere institutions and networks.

Or maybe, as Gigi noted at one point during our conversation, in a playfully serious utterance, that perhaps not all liberation lies in art.