The eighth iteration of Abir India’s First Take 2024 is about to engulf the vivacious city of Ahmedabad. This event is more than just a show; it is a demonstration of the ability of art to erase boundaries and captivate hearts. It’s important to consider Abir India’s extraordinary journey to this point as the expectation grows. Out of scores of entries, about 100 works would be picked by the eminent jury from India. The jury will select the best out of the lot and ten awards in total are awarded.

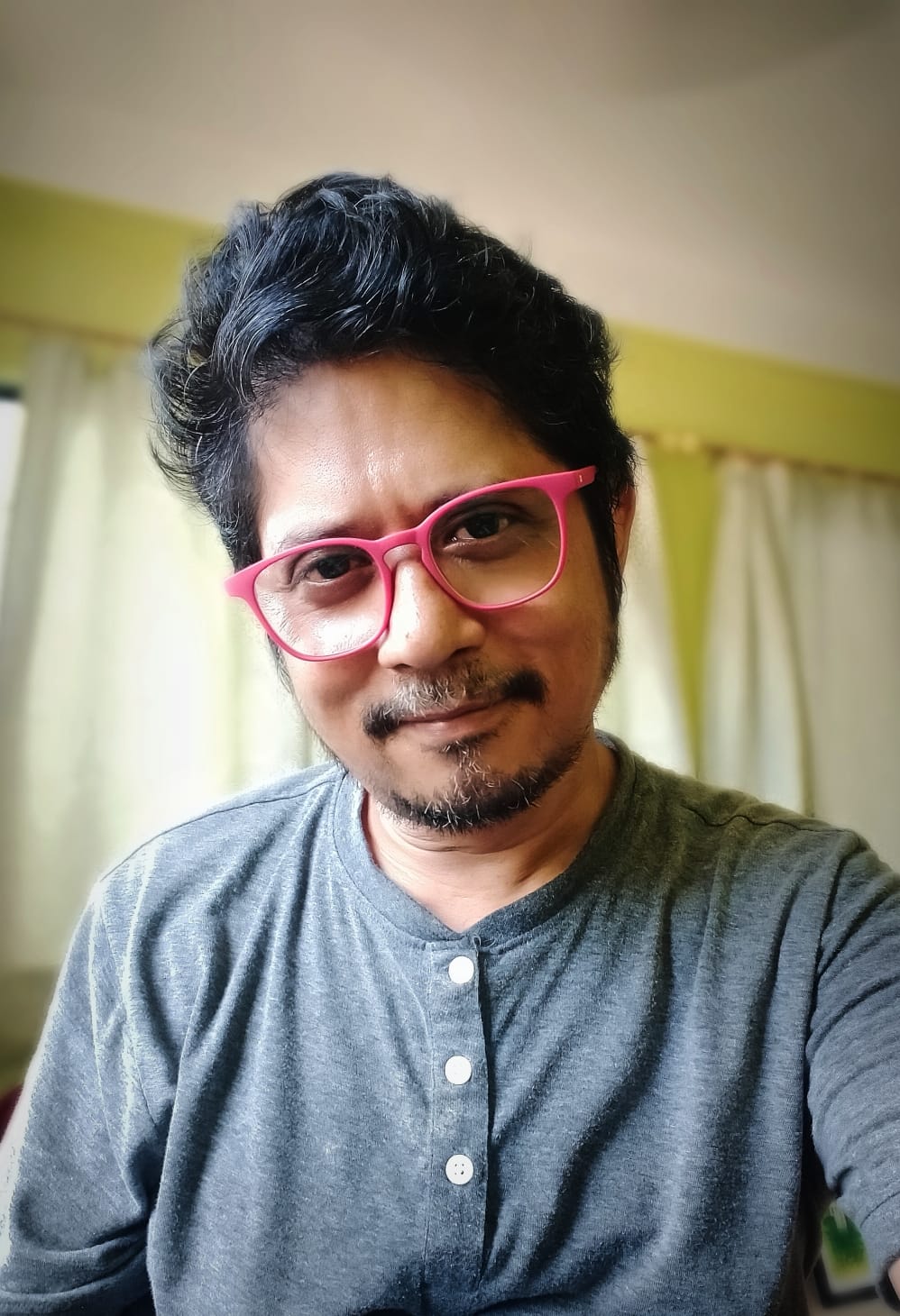

The show will also bring art lovers together, with dialogues, discussions and demonstrations with senior artists, art historians, art critics, curators and investors. For the First Take 2024 , one among the eminent Jury is Veer Munshi. Let’s know more about him and see what expertise he has to offer in Abir India’s First take 2024.

Artist Veer Munshi remembers his early life in Kashmir, his days of mind expansion in Baroda and his relationship with exile and the many shades of minority issues in a conversation with Santanu Borah.

There are enough instances in the history of the human race that shows that conflict mothers great ideas, events and art. The thinking human being always looks for an anchor when they find themselves in circumstances inundated by dark waters of violence. Artist Veer Munshi’s story seems to mirror this historical precedent with great fidelity.

Before we begin, one needs to define the versatility of Veer Munshi. He is not just a visual artist, but also an accomplished curator and an agent provocateur. His art, more often than not, is political and gives voice to the minority, their hopes and dreams that seem to blur out in the din of populist politics and viewpoints. With that in perspective, let’s take you through a journey of Veer’s album of memories, right from the time when Kashmir, his original home, was peaceful and beauty its default setting.

Due to the restrictions of the pandemic, this writer met with Veer over a telephone call. The languid drawl of his measured tone did not give away the turmoil of exile that informs his artistic practice. In fact, the very first question was met with a chuckle:

Writer: “What is your earliest memory?”

Veer: “My earliest memory is of my mother’s womb.”

With this starting point, it was clear that one would have to be incisive while conversing with this keeper of a people’s conscience, the excavator of the complexities of exile.

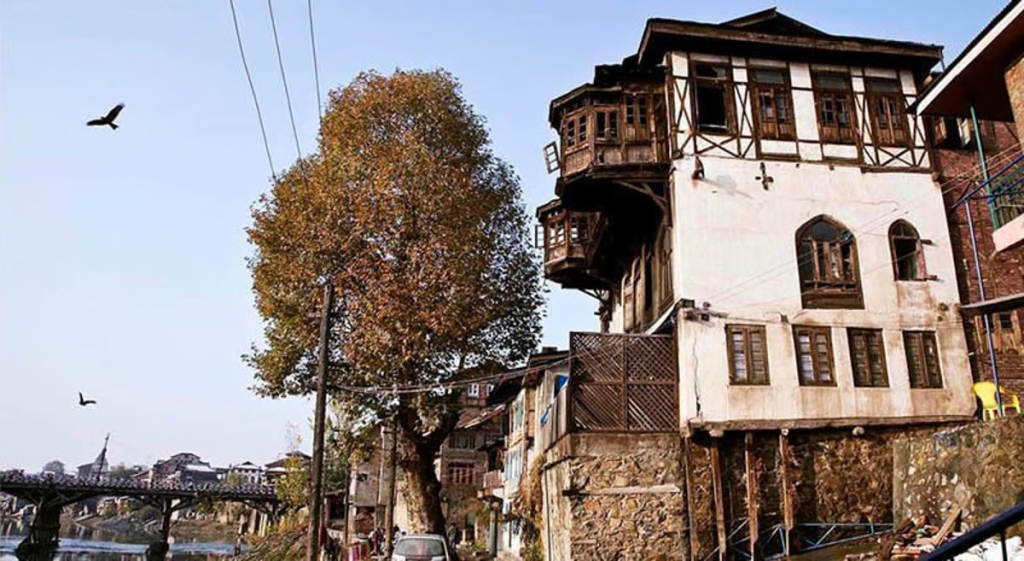

Veer Munshi was your average Kashmiri boy. The earliest days were filled with play, with him and his buddies doing their utmost best to whisk away apples and apricots from their neighbours’ trees and face their indulgent ire in the process. It was a happy time, filled with the innocence of childhood.

During this period there was art too in his life. The music of the mountains has the uncanny ability to arouse the spirit of creativity. Veer and a couple of his friends trundled around the hills and vales, with their landscaping pads and watercolours, turning out idyllic scenes that revel in the translucent beauty of crystal-clear water and crisp air. These paintings came naturally because, well, what do you do when a million colours and the grandeur of a place floating in a utopian frame beckons you? Veer is quick to point out these works helped him understand the importance of skill and draughtsmanship, though at the time it was more of an instinctual activity.

“Art is a gift that you born with. I was confident by the fifth and sixth standard that I could draw and make watercolours. It wasn’t something I questioned or probed. It was all a natural flow,” Veer says, reminiscing about the days when the landscape wasn’t a reminder of the pain the Kashmiris have had to go through.

“Our play was adventurous. We would prowl around the mountains. We also went to the theatre, and in winter we made ice cream and sculptures out of ice. We would also go with our parents to the Mughal Garden. There was political stability and the art college I eventually went to, drew me towards watercolours. On-the-spot watercolour was the tradition of the place. We did the stereotypical landscapes with mountains and streams,” he adds.

Veer’s tryst with exile is grounded in the fact that he was from a Kashmiri Pandit family, who were landlords. The entire family seemed to have a penchant for art: his father, who was a teacher as well, was good at drawing. His brothers and sister too dabbled in painting and showed considerable promise. However, at that time the concept of “being an artist” wasn’t in Veer’s universe. Rather he dreamt of something far removed from the world of art. “I thought I would become a judge or a magistrate. I would see such families and feel very motivated by that. I was impressed by the respect magistrates got. My uncle was a magistrate and that really drove me into wanting to be one. However, when I eventually visited the court and saw how it functioned, I said, ‘rubbish’. That was the end of it.”

An academically bright student, the road ahead cleared out for Veer after he painted a portrait of his headmaster, which was seen by Banshi Parimoo, a popular artist. He was instrumental in guiding Veer to the local art college which had evening classes, a move that was to decide the course of his entire life from there on.

“I remember that teachers had come from M S University in Baroda to our college. It was interesting to get a glimpse of their world view. I was very curious. I wanted to go and study in Baroda and see the wider world. I wanted to escape from Kashmir and then take it as it comes,” he says.

As expected, life change once Veer made it to Baroda. The environment made him see the entire practice of art very differently. The young landscape painter had now come of age. Surrounded by exciting minds who were engaging in contemporary ideas, Veer finally began to see the raison d\’etre for his creative longings. “My history changed after Baroda. In Baroda my whole concept changed, from a stream it became an ocean. For instance, if you paint still life the style is more or less the same everywhere… pot, apple, drapery seem to be everywhere. But in Baroda my first teacher, Nasreen Mohamedi, taught us differently. She urged us to get our own still life, get found objects and make them the subjects of our work. My horizon, obviously, broadened with the likes of Ghulam Mohammed Sheikh, K G Subramanyan and Rattan Parmu engaging with us and pointing us towards newer directions,” he says, dwelling on his initial trysts with some of the greatest artists of post-Independence modern India.

What truly influenced Veer was the fact that he was able to see that making art was not a simply a chore-like activity but a process. One did everything and lived a life in the pursuit of art, in order to find a unique voice that echoed their inner desires. “It was not much about the teaching along but more of the environment around us. There was more freedom conceptually and at that time the figurative narrative art movement was at its zenith. It was provocative. it was Indirect teaching… like KG’s toys, calendars and so on. I would not say there was something like direct learning but by impression created around the students.”

A seemingly “non-artistic activity” that has stayed with Veer is about his teacher Nasreen Mohamedi. “Nasreen would actually sweep studio before we began any work. While initially we did not quite get it but it was a truly holistic way of teaching. We were not only practicing art academically, but also learning about hygiene, how it applies socio-politically, especially in these Covid times. I was about how you practice your life and these value systems only kept growing and made us the artists we are today,” he recounts.

That art was a lifestyle made Veer realise that how you grew as a person affected the art you made and, in fact, enhanced its quality. “Baroda was modern in some sense. The world came here. There were students and teachers from all the states and even foreign countries. An entire cross section of cultural discourse happened here. As you may know, to make good art you have to grow as a person,” he adds.

Elaborating on this growing up process, Veer says that it wasn’t always easy. “There will always be differences with your fellow students and mentors. When you are a student your emotions take over how you act. We would react to something, blast out what we felt and then it would fizzle out. There were times I felt this is not what I have come for. So, I did not paint for two years. One has to grow beyond one’s known vicinity. One must do as much as possible. In order to mature as an artist, one must not ignore skill. A student must learn everything, your plate should be perfect. You should not lose your gift by following trends. Otherwise, your journey becomes an adoption or too derivative. Art is an individual journey,” he adds, emphasizing on the need to practice hard but stand alone.

Heritage and tradition are two words that will surface often when you have a tête-à-tête with Veer. To him they are like anchors. He explains it thus: “Heritage and tradition, our way of life is very crucial. In Baroda I was often confused. Eastern art influenced me, Jamini Roy was fine but the post-Independence western movement was something that I did not much resonate with. I was confused, but luckily Sudir Patwardhan and Ghulam Mohammed Sheikh revived our traditions. I found it easier to identify with that. Miniatures were our thing.”

“With this view firmly planted within me, I began to study the social life in Gujarat and decided to paint it. I followed the Rudali women, or women who are professional mourners. I found their life quite in intriguing and made paintings that reflected and celebrated it,” he adds.

While Veer’s salad days were coming to a close in Baroda, the political climate in Kashmir became increasingly volatile. This had a profound impact on him, as a Kashmir and an artist. “In Kashmir, the landscape no more seemed so beautiful. The political situation put us into cages and made our lives very difficult. That’s when the personal became political. It had all changed. I became a different person on account of this,” he says.

This is where the story of conflict starts in Veer’s life. The exodus of Kashmiri Pandits started somewhere in in 1989, with the concept of “Azadi” getting Islamised. The peak phase of the exodus was in the early 1990s, with the Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front and other pro-Pakistan Islamist insurgents threatening the Hindus populace of the valley. As of 2016, only around 3,000 Kashmiri Hindus remain in the Kashmir Valley compared to approximately 300,000–600,000 in 1990. Clearly, Veer’s worldview changed at the time and this is what he had to say: “I experienced violence. When even a small pebble is thrown into a minority, it creates big ripples. I began to understand minority voice then and it has stayed with me. It was like I was born again. I had to leave my life in Kashmir behind and start again in New Delhi. I had hoped that one day I would go back to my home, as I had left before the mass exodus. But that wasn’t to be, until much later. The Azadi (Freedom) movement was growing and the youth were at the forefront. Not that I believed anything of azadi, but it was all about survival.”

Veer was suspicious of the whole movement because it had a religious colour, something which he despised being a citizen of the world. Azadi or freedom, he said, was not something anybody disliked but the idea of freedom could not be hijacked by political and ideological concerns. “Everybody likes azadi, but it was Islamised and radicalism is not good. The intensity of the movement eventually died down, but when there is a gun culture, you can only say ‘no’ at your own peril. While I had no real idea about the mass exodus, I did go to Shimla to my uncle’s place and then to Jammu to find my parents. After that I came to Delhi. It was tough. I stayed in the Lalit Kala guest house for five days. I would loiter around and sleep in breaks. Money was tough to come by and I was lucky enough to find shelter for some forty bucks a night, and eventually I survived four months like a homeless person. As luck would have it, somebody wanted my art work and I got an advance of Rs 1,500. That was such a happy day. I had good khana (food), my favourite chicken curry. Then I went to the Gahri studio and stood at the door of the community studio, till I finished my work. However, I could not paint pretty pictures due to trauma that I had faced, though the idea was to paint a pretty landscape to sell. Instead, I made a terrorist on a floating land, and that not only taught me, but it was therapeutic as well. This catharsis taught me that art has great power and immense magic,” he reminisces. While the story itself is a tragic one, the conflict and trauma brought out the artist that was to become Veer Munshi.

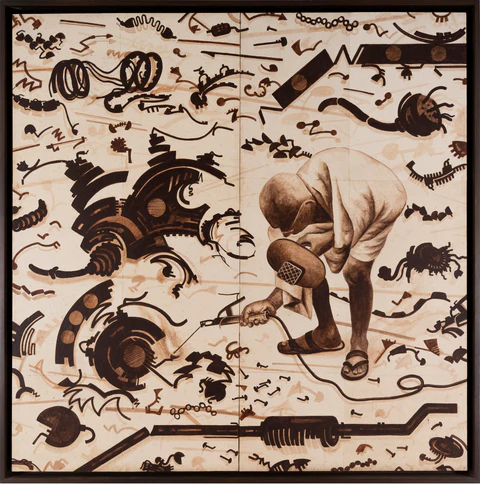

Continuing about his tryst with a newer destiny, he says, “Political art was not the thing that I sought out. I just happened to be my thing. I met the great Ebrahim Alkazi and he gave me my first show in 1992. My works were about human rights and I put out 14 or 15 pieces. This should did not sell out or anything but it did make a dent in the art world at the time. I was called to the United Nations after that show to speak about the situation in Kashmir. After that I did many shows in Mumbai. My journey for over eight years was all about conflict. After that, being in Delhi, my memory slowly began to fizzle and I became a proper city dweller. That was the first time I worked outside the conflict zone, and did a series of 12 paintings entitled ‘Zodiac’. The idea was not to comment on the zodiac signs itself, but to find the luminaries in all the zodiac signs who inspired me. Van Gogh was Aries, Dali was Taurean, Gandhi was Libran, and I also painted my other heroes like Nelson Mandela. I painted Picasso, a Scorpio, who also turned out to be an epic god-like figure in the art world.”

However, the short and seemingly non-political period in Veer’s life soon gave away to his concerns about minorities, exile, and the politics surrounding it, very soon. In 2010, Veer want back to his home Kashmir and also back to political art. He wanted to make art that spoke of his situation and the history of a people whose lives irreparably changed by the exodus and insurgency in the Valley.

One project that he holds dear to himself are the houses that were burned down, vandalised and eventually abandoned during the Kashmir conflict. He says, “I want to document these destroyed homes. I chose to photograph them and I used an FM 2. Many of these homes were familiar houses of my relatives. I did during the winter. The vulnerability of these houses really shook me and I ended up documenting two to three thousand houses. This was my way of sharing my idea of belonging.”

After this sequence of events, Veer began to think about the idea of community very seriously. He realised that he was not alone and that everyone needed to be a part of a larger idea. “That’s when I became more or less an activist. I wanted to find out how to connect communities via art. That’s when I thought of Concourse in Kashmir, where I got 60 artists to put up a show. Unfortunately, while putting up the show a journalist friend of ours was shot dead. But we carried on with our mission. Violence had to be fought back with art and togetherness.”

As we delve into Veer’s work, it becomes clear that his enduring interest, despite his forays into other ideas, remains the problems of exile and migration brought on by situations that are not within one’s control. This idea found expression at the Kochi biennale in 2018, where he created a dargah. “All communities go to dargahs in Kashmir. And this is what I wanted to show in Kochi. I was able to get artists born in an environment of conflict. I wanted to show that there can be one place where everyone could come in and understand their situation and the complexities of their lives,” he says, while talking about the installation. He believes that you cannot simply study history from a perspective where you not a stakeholder, in the sense of understanding an event as it affects humanity as a whole. “For one to understand history truly you have to do your research. In a sense I am dealing with the present and that eventually becomes history. Untruth has no place in the expression of art. Speech might be untrue, but poetry has no untruth in. One cannot weave untruth in art,” he adds, meditating on what connects history and art.

As we close our conversation, it becomes apparent to the writer that maybe, Oscar Wilde, is not all right when he says life imitates art. In Veer Munshi’s case, it is life that turned into art. There was no imitation but an intimate connection between what actually happened and how it was expressed. After this writer ends his call with Veer Munshi (a conversation that could have gone on for a few more hours), he comes back with a simple but profound understanding: that art and life run parallel to each other. Whatever life throws at you becomes what your art speaks of, often more poetically than just being a lament of how things did not turn out the way you thought it would. Veer Munshi’s Kashmir is not just his home, but also the poem of a people still waiting to be completed.

Finally, a few things become clearer: one must face the hunger and the homelessness to express it in a way that is not pretentious. No amount of great explanation will work if the fountain from where the expressions springs itself is untrue. “Without real soul, your art work will be on ventilator,” Veer observes. And that’s where we bid adieu. Maybe, soon he will have found an aesthetic solution to the problems in Kashmir. What is definite is that he has given soul to the pain of Kashmir, and that itself is beautiful.

Former Editor at Abir Pothi