Over the past eight decades, the study of Chinese architectural history has undergone dynamic evolution, shaped by academic collaboration, political upheavals, and a constant quest for understanding the intricate tapestry of China’s rich architectural heritage. From the early foundations laid by pioneers like Liang Sicheng and Liu Dunzhen to the challenges faced during the Cultural Revolution, and the resurgence of research in the subsequent years, the trajectory of Chinese architectural history reflects a cyclical pattern of data collection, compilation, and exploration.

1958-1965: Flourishing Development and National Cooperation

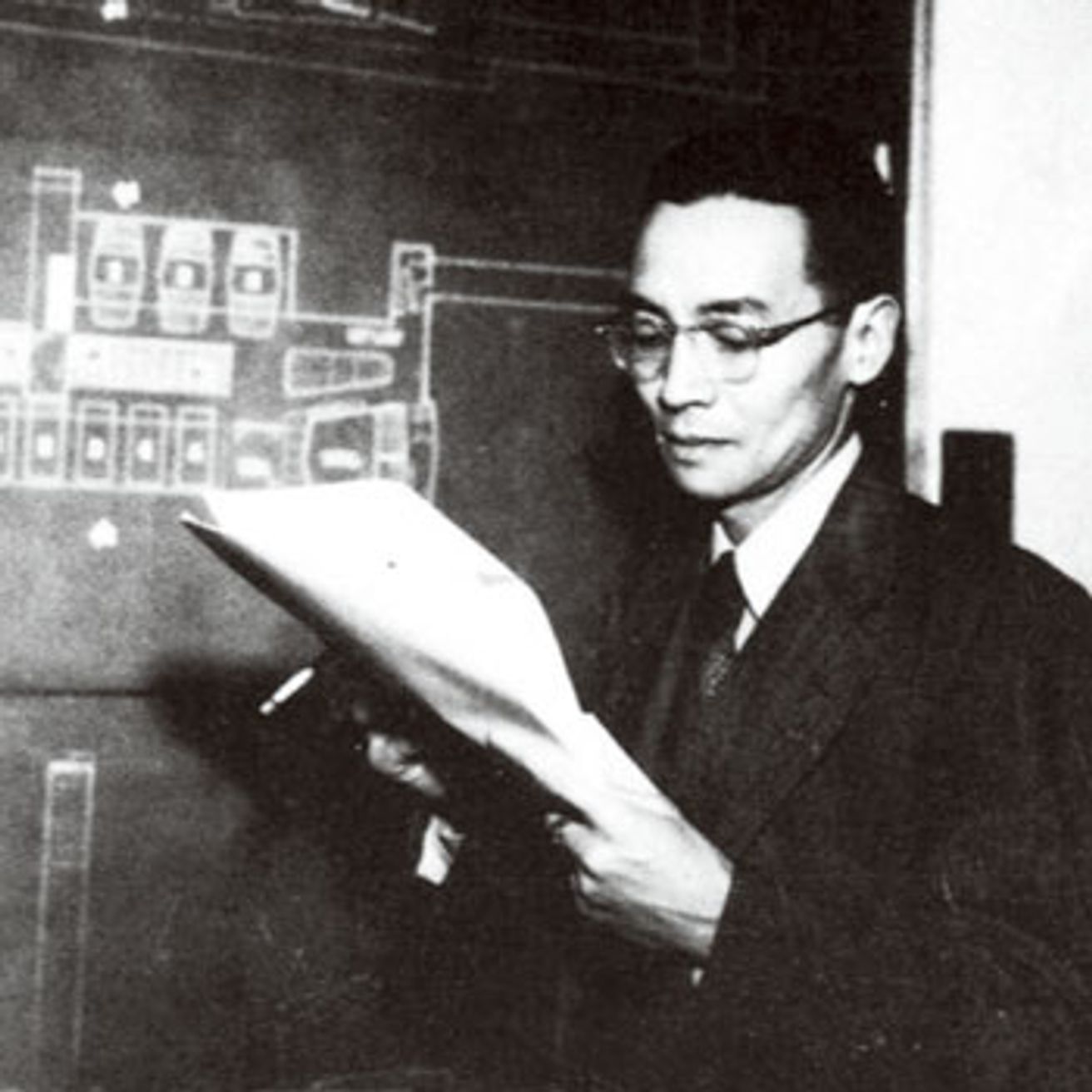

In 1958, under the leadership of Professor Liu Dunzhen, an editorial team embarked on the ambitious task of compiling university-level textbooks, ushering in a period of flourishing development. Noteworthy publications, such as “A Concise History of Chinese Traditional Architecture” and “A Concise History of Chinese Modern Architecture,” set the stage for an extensive exploration of China’s architectural legacy. The monumental illustrated album, “Ten Years of Architecture in New China,” celebrated the nation’s architectural achievements.

Despite the vibrant development, the Cultural Revolution in 1966 abruptly halted nationwide research on architectural history. Founders of the discipline, including Liang Sicheng and Liu Dunzhen, faced public criticism, and the pursuit of knowledge in architectural history was temporarily silenced.

1973-Present: Resilience, Recovery, and Contemporary Challenges

The resumption of work on architectural history in 1973 marked a period of resilience and recovery. As institutions reopened, the disciples of Liang Sicheng and Liu Dunzhen continued their work. Monographs, such as “Chinese Islamic Architecture” and “Research on the Regulations of the Yingzao Fashi,” emerged during this time, contributing to the expansion of architectural knowledge.

The years from 1980 to 1995 witnessed the compilation of four major reference works, addressing traditional building technology, cities, architecture, and landscape architecture. This period also saw the release of a revised edition of “History of Chinese Traditional Architecture,” offering a deeper understanding with expanded historical data and theoretical analysis.

The 1990s brought a focus on the artistic features of architecture, exemplified by the compilation of “History of Chinese Architectural Art.” Scholars delved into aesthetics with works like “Chinese Architectural Aesthetics.”

Future Directions and Challenges

As Chinese architectural history enters a new phase, the field faces both opportunities and challenges. The vast amount of historical data must now be viewed in the context of city planning, architecture, and landscape architecture. The emphasis on technology and excavation provides a crucial context for understanding architectural evolution.

A critical goal for future research lies in developing a comprehensive theory of Chinese architectural history. Moving beyond technical and historical aspects, the field should explore the aesthetic dimensions of Chinese architecture, providing a foundation for the creation of modern cities and buildings with a distinctly Chinese character.

In retrospect, the eighty-year journey through Chinese architectural history mirrors a resilient pursuit of understanding, marked by periods of flourishing development, political challenges, and subsequent recovery. From its interdisciplinary foundations to the exploration of diverse building types, regional variations, and the influences of multi-ethnicity, the field has evolved cyclically. The post-Cultural Revolution resurgence showcased the commitment of scholars to preserving China’s architectural heritage, culminating in major reference works and renewed emphasis on aesthetics. As the discipline looks to the future, opportunities and challenges abound, with a call to contextualize historical data, emphasize technology, and develop a comprehensive theory. Chinese architectural history stands poised not only to bridge the gap between tradition and modernity but also to inspire a distinctively Chinese architecture that harmonises the lessons of the past with the aspirations of the future.

Reference:

Understanding Chinese Research Work on Architectural History Author(s): Fu Xinian Source: Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians , Vol. 73, No. 1 (March 2014), pp. 12-16 Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the Society of Architectural Historians

Feature Image Courtesy: Architizer

Piet Mondrian’s Neoplasticism: Art finds harmony in the simplest forms and colours